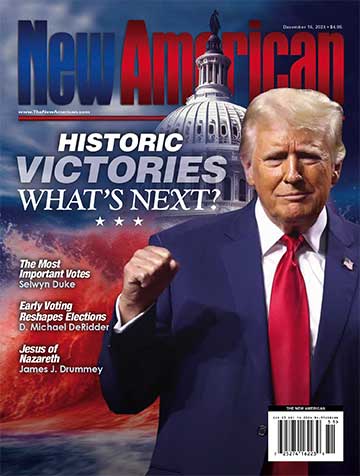

In a statement issued by her office July 11, Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen G. Kane (shown) announced that the Office of Attorney General will not defend Pennsylvania’s Defense of Marriage Act in a recently filed lawsuit (Whitewood v. Corbett). The lawsuit challenges Pennsylvania’s Defense of Marriage Act, based on the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

“I cannot ethically defend the constitutionality of Pennsylvania’s version of DOMA where I believe it to be wholly unconstitutional,” Kane said. “It is my duty under the Commonwealth Attorneys Act whenever I determine it is in the best interest of the Commonwealth to authorize the Office of General Counsel to defend the state in litigation.”

“Additionally, it is a lawyer’s ethical obligation under Pennsylvania’s Rules of Professional Conduct to withdraw from a case in which the lawyer has a fundamental disagreement with the client,” added Kane.

Regardless of the language used by Kane to justify her disregard of state law, the fact is, she has chosen to personally nullify a law she believes violates the Constitution.

Such a posture is curious in light of the staunch opposition to nullification by most people of Kane’s political bent.

In the past, political scientists, self-proclaimed constitutional historians, and elected officials fond of federal power have disparaged nullification as “nuts” and a “bizarre fad.”

One of these nullification naysayers wrote a blog post on MSNBC declaring, “Not to put too fine a point on this, but there’s nothing to discuss — state lawmakers can’t pick and choose which federal laws they’ll honor.”

Seems state legislators can’t pick and choose which federal laws they’ll honor unless that federal law violates their personal philosophy.

“I know that in this state there are people who don’t believe in what we are doing, and I’m not asking them to believe in it. I’m asking them to believe in the constitution,” Attorney General Kane said in the press release.

Although Kane’s definition of marriage is wrong, her sense of when state officials should resist federal attempts to legislate where there is not constitutional authority is spot on.

When Washington decides to go walkabout, however, and start legislating (or issuing edicts, in the case of President Obama) in areas not within its constitutional boundaries (healthcare, education, gun ownership), the states reserve the right to check that usurpation by refusing to afford such acts the power of law. Conversely, it would be a usurpation on the part of the states should they attempt to disregard federal laws that are constitutionally sound.

In the case at hand, there is not a single word in the Constitution that grants the federal government the power to define marriage.

The 10th Amendment makes clear that if any power is “not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states,” that power is “reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

The right of states to refuse to enforce unconstitutional federal acts is known as nullification.

Nullification is a concept of constitutional law recognizing the right of each state to nullify, or invalidate, any federal measure that exceeds the few and defined powers allowed the federal government as enumerated in the Constitution.

Nullification exists as a right of the states because the sovereign states formed the union, and as creators of the compact, they hold ultimate authority as to the limits of the power of the central government to enact laws that are applicable to the states and the citizens thereof.

Constitutionally speaking, then, whenever the federal government passes any measure not provided for in the limited roster of its enumerated powers, those acts are not awarded any sort of supremacy. Instead, they are “merely acts of usurpation” and do not qualify as the supreme law of the land. In fact, acts of Congress are the supreme law of the land only if they are made in pursuance of its constitutional powers, not in defiance thereof.

Hamilton put an even finer point on the issue when he wrote in The Federalist, No. 78, “There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the constitution, can be valid.”

Constitutionally speaking, then, states are right to refuse to enforce unconstitutional federal acts, including DOMA. Kane’s refusal brings up a separate issue: Whether the practice of by state officials — rather than state legislators — is a constitutionally sound expression of nullification.

First, the analysis should consider the obligations of the state attorney general as set forth in the Pennsylvania state constitution.

Article IV, Section 4 of the Pennsylvania constitution establishes that the attorney general “shall be the chief law officer of the Commonwealth and shall exercise such powers and perform such duties as may be imposed by law.”

Shall perform such duties as imposed by law, not “may do so unless she disagrees with it.”

In a statement, the Pennsylvania Office of General Counsel seems to agree, “We are surprised that the attorney general, contrary to her constitutional duty under the Commonwealth Attorneys Act, has decided not to defend a Pennsylvania statute lawfully enacted by the General Assembly, merely because of her personal beliefs,” Pennsylvania General Counsel James D. Schultz said in a statement.

Additionally, the Commonwealth Attorneys Act of 1980 defines the duties of an elected attorney general. Included among those duties is the obligation:

To represent the commonwealth and all commonwealth agencies and upon request the auditor general, state treasurer and Public Utility Commission in any action brought by or against the commonwealth or its agencies; to furnish upon request legal advice to the governor or the head of any commonwealth agency.

Attorney General Kathleen Kane’s announcement that she “cannot in good conscience” defend duly enacted state law violates this provision of the Commonwealth Attorneys Act.

Of course, should Kane decide ultimately that her duty to her conscience trumps her duty to the state constitution (and there is an argument to made that it certainly should), she is not left without recourse: She may resign.

Finally, the divergence between Kane’s refusal to enforce state law and a state’s refusal to enforce an unconstitutional federal law is evident. The United States of America is a union of sovereignties. If one or more of the parties to the compact that created the union esteem some federal act to be beyond the authority of the federal government, then it or they are strengthening the Constitution by insisting that its restrictions on power be recognized.

In the case of Kane and DOMA, Kane’s instinct is correct insofar as the proper respect that should be afforded unconstitutional federal acts. Where she runs afoul of principle, however, is in her decision to assume the power to pick and choose among lawfully enacted state statutes.

Pennsylvania has chosen to enact a state version of the federal Defense of Marriage Act. Constitutionally speaking, states may act in innumerable areas where the federal government is forbidden to enter. As James Madison explained in The Federalist, 45, “The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the Federal Government, are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State Governments are numerous and indefinite.”

In the case of marriage, the state legislature of Pennsylvania is within its rights to define that term to be the union of a man and woman, as well as to restrict its benefits to those who comply with that legal definition and to deny those same benefits to those who do not.

The federal government does not have such a prerogative.

But, that has no impact on Attorney General Kane’s decision to violate her constitutional responsibility to enforce state law. The Constitution of the state of Pennsylvania is very clear: The attorney general must perform her legal duties, duties defined by the constitution, the Commonwealth Attorneys Act, and the state legislature. Her open and hostile refusal to do so is grounds for her removal from office, assuming she doesn’t manifest the strength of the restraints of her conscience by resigning.

Photo of Kathleen Kane: AP Images

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American and travels frequently nationwide speaking on topics of nullification, the NDAA, and the surveillance state. He can be reached at [email protected].