As he prepared to leave office, President George Washington was concerned about the partisan and martial path the young republic he helped found was heading down.

Even the “Father of His Country” was not above criticism and vitriolic attacks in the press. Although the recently retired general whom the Indians believed could not be killed loathed the shots taken at him by “infamous newspapers,” he refused to make any response that would deny his countrymen of “the infinite blessings resulting from a free press.”

This noble attitude contrasts sharply with his contemporary and successor John Adams who signed the Alien and Sedition Acts into law in an attempt to criminalize criticism of the president, as well as the vigorous defense currently being mounted by our current president of his authority under the National Defense Authorization Act to indefinitely detain persons he suspects of posing a threat to the security of the homeland.

In this and in myriad other ways, Washington was in fact “the indispensable man” and an example to politicians in his own time and ours.

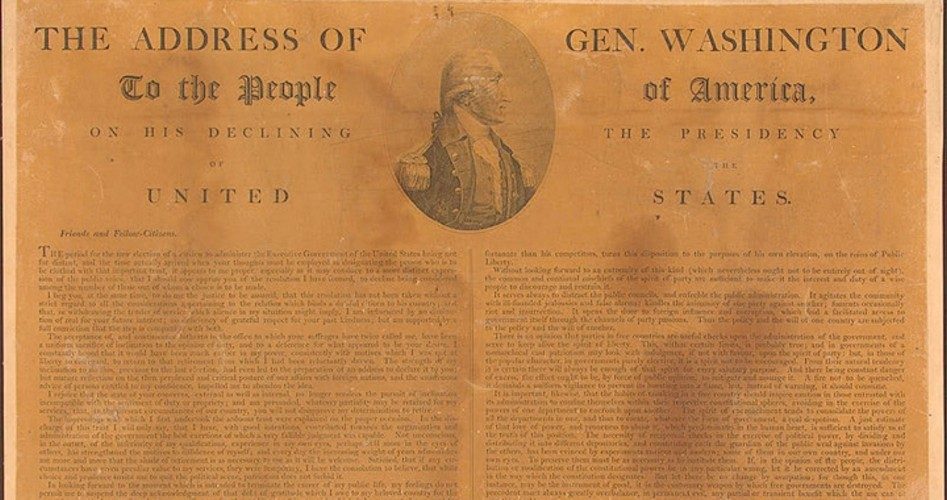

When the time came for Washington to return to his beloved Mount Vernon and deliver one last message to his “friends and fellow citizens,” he relied on his former collaborator and Virginian James Madison to help him draft his Farewell Address.

September 19, 2012 marked the 216th anniversary of Washington’s Farewell Address. Deservedly so, this speech has become renowned for its prose and principles — including national unity, tolerance of political differences, and neutrality in the endless foreign conflicts.

To ensure that his remarks would strike the appropriate tone, Washington informed Madison that the speech should declare “in plain and modest terms … that we are all children of the same country…. That our interest, however diversified in local and small matters, is the same in all the great and essential concerns of the nation.”

Although he penned a version of the address in his own words, he ultimately approved and delivered the words written by Madison.

After rehearsing his own record of political and military service and expressing his “love of liberty,” Washington urges the states to remain united and to “avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.”

In this case and in so many others, the United States has failed to follow President Washington’s wise recommendations.

Our military-industrial complex is immense, and counts profits in the billions derived from supplying our armed forces currently deployed around the globe. Defense contractors sign billion-dollar contracts with the government, and funnel millions into the campaign coffers of key congressmen whom they can count on to keep the money flowing and the troops fighting.

To avoid the plague of perpetual war, Washington warns against “foreign alliances, attachments, and intrigues.”

Sadly, our modern proclivity is to surrender sovereignty to international bodies whose members are not elected and thus not accountable to the American people, and to send monetary and military support to “freedom fighters” in the Middle East. As the murder of the U.S. ambassador to Libya demonstrates, however, all this patronage has failed to purchase peace.

Washington associates a lasting peace with the avoidance of martial meddling and with the level of virtue in the citizenry. He declares that a peaceful country can be maintained only by peaceful people. Washington explains:

Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all. Religion and morality enjoin this conduct; and can it be, that good policy does not equally enjoin it — It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and at no distant period, a great nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence. Who can doubt that, in the course of time and things, the fruits of such a plan would richly repay any temporary advantages which might be lost by a steady adherence to it? Can it be that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a nation with its virtue? The experiment, at least, is recommended by every sentiment which ennobles human nature. Alas! is it rendered impossible by its vices?

Our own government’s defiance of this good advice is apparent by its efforts to portray Muslims as radicals and enemies worthy of hate and suspicion; as well as by its codified disregard for due process as evidence by the compilation by President Obama of a kill list composed of people (including some Americans) targeted for summary execution.

In light of Washington’s wise warnings, it is little wonder that we find ourselves trillions of dollars in debt due in part to the demand for the funding of multiple military operations, as the Constitution, the rule of law, and virtue are counted among the collateral damage.

The history of the past 216 years reveals that most of Washington’s successors have refused to heed the counsel of caution given in his Farewell Address. Instead, they have chosen to bid farewell to the “fundamental maxims of true liberty” included by him and his fellow delegates in the Constitution.

If we are to avoid “running the course which has hitherto marked the destiny of nations,” perhaps President Obama, Mitt Romney, and those members of Congress so keen on banging the war drums will take a moment and refresh their memories of our first president’s parting words. The following declaration is particularly timely:

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow-citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government. But that jealousy to be useful must be impartial; else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defense against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots who may resist the intrigues of the favorite are liable to become suspected and odious, while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people, to surrender their interests.

Finally, perhaps all of us can turn from those habits and long-held prejudices that prevent us from achieving that standard of virtuous nobility recommended by Washington. Perhaps we can turn back to that God that gave us life and is the Author of our liberty. As Washington said and Madison wrote:

Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope that my country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that, after forty five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.

Relying on its kindness in this as in other things, and actuated by that fervent love towards it, which is so natural to a man who views in it the native soil of himself and his progenitors for several generations, I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I promise myself to realize, without alloy, the sweet enjoyment of partaking, in the midst of my fellow-citizens, the benign influence of good laws under a free government, the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers.