Before the English founded Jamestown in the Virginia Colony on May 14, 1607, work had already begun on what has been called “the noblest monument of English prose.” The Authorized Version of the Bible, more commonly known as the King James Version because it was translated under the authority of King James I of England, was begun in 1604. This year marks the quatercentenary, or four-hundredth anniversary, of its publication. But although we know the day and month of the founding of Jamestown, all we know about the publication date of the Authorized Version is the year — 1611.

Although the King James Bible was not the first Bible translation into English from the original languages, it is widely regarded as the most important and most influential English translation of the Bible. But that is not all. The King James Bible is also universally recognized as a significant literary work and a landmark in the history of the English language.

The Noblest Monument of English Prose

The place of the Authorized Version in English literature is a story that has often been told. “Historically,” said Geddes MacGregor, former distinguished professor of philosophy at USC and author of A Literary History of the Bible: From the Middle Ages to the Present Day, “it is the most influential version of the most influential book in the world, in what is now its most influential language.” It was Robert Lowth, one-time professor of poetry at Oxford, who termed the Authorized Version “the best standard of our language” and “the noblest monument of English prose.” Perhaps the most-quoted sentiment about the Authorized Version is that of the historian and poet Thomas Babington Macaulay: “A book which, if everything else in our language should perish, would alone suffice to show the whole extent of its beauty and power.”

Even opponents of religion have weighed in on the merits of the Authorized Version. The journalist and social critic H. L. Mencken stated:

It is the most beautiful of all the translations of the Bible; indeed it is probably the most beautiful piece of writing in all the literature of the world…. Its English is extraordinarily simple, pure, eloquent, and lovely. It is a mine of lordly and incomparable poetry, at once the most stirring and the most touching ever heard of.

And then there is George Bernard Shaw, the Irish playwright and Nobel Prize winner in Literature:

The translation was extraordinarily well done because to the translators what they were translating was not merely a curious collection of ancient books written by different authors in different stages of culture, but the word of God divinely revealed through his chosen and expressly inspired scribes. In this conviction they carried out their work with boundless reverence and care and achieved a beautifully artistic result.

The influence of the Authorized Version on the English language is another story that has often been told, as the aforementioned Geddes MacGregor explains:

The literary influence of the King James Version is well known. Not even Shakespeare has more profoundly affected our literature. The most godless of men, provided only that he has inherited English for his mother tongue, is confronted with the influence of the King James Version of the Bible almost wherever he turns. It has been injected into the stream of the language. It has invigorated and enriched all subsequent English prose.

Frederic Kenyon adds that “so deeply has its language entered into our common tongue, that one probably could not take up a newspaper or read a single book in which some phrase was not borrowed, consciously or unconsciously, from King James’s version.” Examples could be multiplied:

“fire and brimstone” (Gen. 19:24)

“apple of his eye” (Deu. 32:10)

“stole his heart” (2 Sam. 15:6)

“skin of my teeth” (Job 19:20)

“root of the matter” (Job 19:28)

“at his wit’s end” (Psa. 107:27)

“drop in a bucket” (Isa. 40:15)

“eye to eye” (Isa. 52:8)

“handwriting on the wall” (Dan. 5:5)

“he is beside himself” (Acts 26:24)

“powers that be” (Rom. 13:1)

“through a glass darkly” (1 Cor. 13:12)

Although all of these phrases may not have originated with the King James Bible, they live in the English language because of it.

But the influence of the Authorized Version cannot be limited to just English language and literature, as MacGregor again explains:

The King James Bible, though indeed the greatest literary monument of the English-speaking world, has never been merely a literature. It has guided through the path of life and the valley of death a billion hearts and minds that it has taught, consoled, and enlightened.

And more recently, Jaroslav Pelikan, the late Sterling Professor Emeritus of History at Yale University, in his book Whose Bible Is It? A History of the Scriptures Through the Ages, remarks that “the King James Version stands as a monument of English prose and also as an abiding contribution of the English Reformation not only to the spirituality but to the culture of the entire English-speaking world.”

King James and the ?Hampton Court Conference

The story of the King James Bible actually begins in the Elizabethan Age. As the reign of Queen Elizabeth I was coming to a close, we find a draft for an act of Parliament for a new version of the Bible: “An act for the reducing of diversities of Bibles now extant in the English tongue to one settled vulgar translated from the original.” Aside from Tyndale’s Bible (actually just the New Testament and parts of the Old), there were extant English versions of the Bible by individuals: Miles Coverdale (1535), Thomas Matthew (1537), and Richard Taverner (1539); and committees: the Great Bible (1539), the Geneva Bible (1560), and the Bishops’ Bible (1568). There was also published during this time the Rheims New Testament in 1582, followed by the Douay Old Testament (in two volumes) in 1609 and 1610. These together became the Douay Rheims Bible, which is still published today and regarded by Catholics as a faithful translation. After the death of Elizabeth in 1603, she was succeeded by James I, as the throne of England passed from the Tudors to the Stuarts.

King James I, who lived from 1566-1625, had already been James VI of Scotland for 36 years. His accession to the throne of England began the process, not only of uniting the two countries under one head, but uniting all of Protestant Christendom under one Bible. Although there were other claimants to the throne, James was the obvious choice to succeed the childless Elizabeth. He was male, he already had male heirs, he was experienced, and he was Protestant. This latter point was especially important because by the Act of Supremacy, the English monarch was also the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.

One of the first things done by the new King was the calling of the Hampton Court Conference in January of 1604 “for the hearing, and for the determining, things pretended to be amiss in the church.” Although it was at the Hampton Court Conference that the proposal was made for a new translation of the Bible, the conference was primarily an attempt to settle the issue of Puritanism in the Church of England. The Puritans desired a more complete reformation in the Church. Extreme Puritans rejected the official Book of Common Prayer and the episcopal form of church government. Moderate Puritans merely objected to certain rites and ceremonies.

King James was keenly interested in theological and ecclesiastical matters and quite at home in disputes of this nature. Although he sought to be a reconciler of religious differences, he was more interested in conformity. At the Hampton Court Conference, a delegation of moderate Puritans met with the King and his bishops, deans, and advisors. Several of the men who attended the conference were later chosen to be translators of the proposed new Bible.

The Puritan delegates at Hampton Court had been instructed to propose some moderate reforms. Although a new translation of the Bible was not on the agenda, according to William Barlow, who attended the conference in his capacity as the dean of Chester, on the second day of the conference, John Rainolds, the Puritan president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, “moved his majesty that there might be a new translation of the Bible, because those which were allowed in the reign of King Henry the Eighth and Edward the Sixth were corrupt and not answerable to the truth of the original.” The King rejoined that “he could never yet see a Bible well translated in English; but I think that, of all, that of Geneva is the worst.” He then expressed his desire “that some special pains should be taken in that behalf for one uniform translation” undertaken “by the best learned in both the universities, after them to be reviewed by the bishops, and the chief learned of the church; from them to be presented to the privy council; and lastly, to be ratified by his royal authority.” A resolution accordingly came forth that “a translation be made of the whole Bible, as consonant as can be to the original Hebrew and Greek; and this to be set out and printed, without any marginal notes, and only to be used in all churches of England in time of divine service.”

The Hampton Court Conference and the King’s sponsoring of the new translation were both alluded to in the dedication at the front of the new Bible called the “Epistle Dedicatory.” And although he had no part in the Bible’s translation, James was therein referred to as “the principal mover and Author of the Work.” In the Bible’s preface called “The Translators to the Reader,” there is specific mention of both events, as there was at the King’s funeral. This is why the new Bible was early on referred to as King James’s Bible.

The King James Translators

The next step was the actual selection of the men who were to perform the work. In July of 1604, King James wrote to Bishop Bancroft, the “chief overseer” of the work, that he had “appointed certain learned men, to the number of four and fifty, for the translating of the Bible.” These men were the best biblical scholars and linguists of their day. In the preface to their completed work it is further stated that “there were many chosen, that were greater in other men’s eyes than in their own, and that sought the truth rather than their own praise. Again, they came or were thought to come to the work, learned, not to learn.” Other men were sought out, according to James, “so that our said intended translation may have the help and furtherance of all our principal learned men within this our kingdom.”

Although 54 men were nominated, most ancient lists of the translators only contain the names of 47 men. The translators were organized into six companies: two to meet at Westminster, two at Cambridge, and two at Oxford. The Westminster Old Testament company was assigned Genesis through 2 Kings. The Westminster New Testament company handled the Epistles. The first group of Cambridge translators worked on 1 Chronicles through Song of Solomon. The second Cambridge group translated the Apocrypha, which appeared in the early editions of the new Bible between the Old and New Testaments. The Oxford Old Testament company was assigned the Prophets and Lamentations. The Oxford New Testament company handled the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation. There is evidence that the work was subdivided within the companies.

In the dedication to their work, the translators modestly stated: “We are poor Instruments to make GOD’S holy Truth to be yet more and more known unto the people.” In their preface, they further mention that “there were many chosen, that were greater in other men’s eyes then in their own, and that sought the truth rather than their own praise.” All of the translators belonged to the established church, although some were Puritans. All but one were ordained ministers. Some were or were later made bishops. Some were doctors of divinity. Six translators had been at the Hampton Court Conference.

The Translators at Work

The work on the new translation began in earnest in 1604 and progressed steadily. Unlike the Hampton Court Conference, of which we have an “official” account and some other records, there is no account, official or otherwise, of what transpired between the starting point in 1604 and the completion of the work in 1611. There are, however, some things that survive that provide a glimpse of what happened. There are a few statements in the translators’ preface about their work. There are some original letters, documents, and manuscripts that relate in some way to the translators’ work. There are six major pieces of evidence: the rules given the translators, a report made by the British delegation to the Synod of Dort, a biography of one of the translators, the notes of one of the translators, and two volumes actually used by the translators that record their work in progress.

Fifteen general rules were advanced for the guidance of the translators. Additional knowledge about the translators’ guidelines can be found in the report of the British delegation to the Synod of Dort in 1618 that paraphrased three of the original rules and added some others related to certain matters of practice that were evidently decided while the work was in progress. There is extant a biography of the translator John Bois that contains information about his role as a translator and final reviser. There are also Bois’s notes of the proceedings of the general meeting of the translators who prepared the final revision. Another major source of information is a complete 1602 Bishops’ Bible with annotations by the translators. The last major piece of evidence about the work of the translators is a large manuscript that shows the translators’ work on the Epistles at an earlier stage.

The resources at the disposal of the translators were diverse and many. The title page of the Authorized Version contains the statement: “newly translated out of the original tongues: and with the former translations diligently compared and revised.” Regarding the original tongues, we read in the translators’ preface:

If you ask what they had before them, truly it was the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, the Greek of the New. These are the two golden pipes, or rather conduits, wherethrough the olive branches empty themselves into the gold.

And, as the translators themselves also acknowledged, they had a multitude of sources from which to draw: “Neither did we think much to consult the Translators or Commentators, Chaldee, Hebrew, Syrian, Greek or Latin, no nor the Spanish, French, Italian, or Dutch.” In addition to the works of the ancients, there were available the early Hebrew Bibles, numerous editions of the Greek New Testament, various polyglots, and versions in Latin, German, Italian, French, Bohemian, Spanish, Slavonic, Serbian and Croatian, Portuguese, Danish and Norwegian, Arabic, Russian, and Polish. As related by Bible historian Edwin Willoughby, formerly the chief bibliographer at the Folger Shakespeare Library: “No portion of the Scriptures in English was printed until after all or a part of the Bible had appeared in the languages of almost every country in Europe.” In addition to all these resources, the Bodleian Library contained numerous reference works.

Besides the official rules, and the additions mentioned in the British report to the Synod of Dort, there are some indications of how the translators went about their work. The printer supplied 40 large church Bibles for the use of the translators. The translators were exacting and particular in their work, as related in their preface:

Neither were we barred or hindered from going over it again, having once done it.

Neither did we disdain to revise that which we had done, and to bring back to the anvil that which we had hammered: but having and using as great helps as were needful, and fearing no reproach for slowness, nor coveting praise for expedition, we have at the length, through the good hand of the Lord upon us, brought the work to that pass that you see.

The report of the British delegation to the Synod of Dort also supplies the following four things about how the work was carried out:

Firstly, in the distribution of the work he willed this plan to be observed: the whole text of the Bible was distributed into six sections, and to the translation of each section there were nominated seven or eight men of distinction, skilled in languages.

Two sections were assigned to certain London theologians; the four remaining sections were equally divided among the theologians of the two Universities.

After each section had finished its task twelve delegates, chosen from them all, met together and reviewed and revised the whole work.

Lastly, the very Reverend the Bishop of Winchester, Bilson, together with Dr. Smith, now Bishop of Gloucester, a distinguished man, who had been deeply occupied in the whole work from the beginning, after all things had been maturely weighed and examined, put the finishing touch to this version.

After recording that “three copies of the whole Bible” were sent to London from Cambridge, Oxford, and Westminster,” Bois’s biographer states that a new choice was made out of some of the translators “to review the whole work, and extract one out of all three, to be committed to the press.” Writing in the latter part of the first half of the 17th century, the historian and jurist John Selden also described the work of the translators:

The translation in King James’s time took an excellent way. That part of the Bible was given to him who was most excellent in such a tongue (as the Apocrypha to Andrew Downs) and then they met together, and one read the Translation, the rest holding in their Hands some Bible, either of the learned Tongues, or French, Spanish, Italian, etc. if they found any Fault they spake, if not, he read on.

Putting all of the available information together, Ward Allen has nicely summarized the whole process:

Each translator completed his revision of a chapter week by week, and each company forged a common revision by comparing these private revisions. This revision being completed, a company circulated its work, book by book, among the other companies. From this circulation there resulted revisions, made in the light of objections raised to the work of a company, and an excursus upon any objection which the original company did not agree to. Then the translators circulated their work among the learned men, who were not official translators, and revised their work in view of suggestions from these men. Now the translators had to circulate these revisions among the other companies. Then, they prepared a final text. This final text they submitted to the general meeting in London, which spent nine months compounding disagreements among companies.

This general meeting occupied a nine-month period during the years 1609-1610 at Stationers’ Hall. The final step was the “finishing touch” by Thomas Bilson and Miles Smith. This could have included the chapter summaries and headings. It is Bilson who is credited with writing the “Epistle Dedicatory” that appeared at the front of the new version. The preface was written by Smith, as is also confirmed by the biographical preface to the 1632 edition of Smith’s published sermons.

The King James Bible

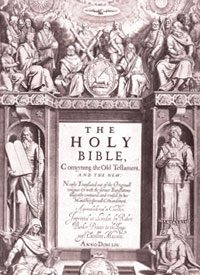

The completed work of 788,258 words was issued sometime in 1611. The first edition was a large folio with a page size of roughly 11 by 16 inches. The ornate engraved title page depicts the Trinity in the upper panel in the form of the Divine Name, a dove, and a lamb. The oval frame containing the lamb is surrounded by the Apostles. At each corner of the engraving sit, with pen in hand, the writers of the four Gospels: Matthew at the top left, Mark at the top right, Luke at the bottom left, and John at the bottom right. Moses and Aaron stand in niches astride the title, which in modern English reads:

The Holy Bible, Containing the Old Testament, and the New. Newly Translated out of the Original Tongues: and with the Former Translations Diligently Compared and Revised by His Majesty’s Special Commandment. Appointed to be Read in Churches. Imprinted at London by Robert Barker, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty. Anno Dom. 1611.

The New Testament had a separate title page. It is a woodcut with the title, the four Gospel writers, and emblems of the Trinity surrounded by the Twelve Apostles on the right and the tents of the Twelve Tribes of Israel on the left. The whole of it reads:

The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Newly Translated out of the Original Greek: and with the former Translations diligently compared and revised, by his Majesty’s special Commandment. IMPRINTED at London by Robert Barker, Printer to the Kings’ most Excellent Majesty. ANNO DOM. 1611.

The three-page “Epistle Dedicatory” begins the volume. This is still printed in some modern editions of the Authorized Version. This was followed by the 11-page translators’ preface, “The Translators to the Reader.”

Then and Now

The Authorized Version soon eclipsed all previous English versions of the Bible. David Norton, English professor at the University of Wellington in New Zealand and modern authority on the King James Bible, remarks that “by the Restoration in 1660, we may conclude, initial dissatisfaction had had its day: the KJB was now established as the English Bible and was generally regarded as an accurate rendering of the originals.” Subsequent versions of the Bible were likewise eclipsed, for the Authorized Version was generally considered to be the Bible in the Protestant world until the advent of the Revised Version in 1881 and the ensuing stream of modern translations. As explained by the British theologian and English Bible historian Alister McGrath:

In popular Christian culture, the King James translation is seen to possess a dignity and authority that modern translations somehow fail to convey. Even four hundred years after the six companies of translators began their long and laborious task, their efforts continue to be a landmark for popular Christianity. Other translations will doubtless jostle for place in the nation’s bookstores in the twenty-first century. Yet the King James Bible retains its place as a literary and religious classic, by which all others continue to be judged.

The King James translators could not have imagined the lasting significance of their work. Yet, they did express in their preface: “Truly (good Christian Reader) we never thought from the beginning, that we should need to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one … but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one, not justly to be excepted against, that hath been our endeavor, that our mark.”

With four hundred years of history to look back on, and hundreds of millions of copies printed, I think it is evident that they succeeded.

Laurence M. Vanceis the author of A Brief History of English Bible Translations; King James, His Bible, and Its Translators; and Archaic Words and the Authorized Version.