One of Britain’s most notorious monarchs, made famous through the centuries thanks in large part to William Shakespeare, has stepped onto the stage once more. The remains of King Richard III, who reigned in England for just two years before being killed in 1585 at the Battle of Bosworth Field, were discovered under a parking lot in the city of Leicester, 100 miles northwest of London. Researchers at the University of Leicester, who uncovered the remains at the dig site of what had been a medieval church, Grey Friars, said that the evidence shows “beyond reasonable doubt” that the battle-scarred skeleton found last October is that of the Richard.

USA Today noted that the remains “had what was thought to be a metal arrow in its back — in fact, more likely to be a Roman nail — and head injuries,” injuries that match the historical account of how the king died in battle. The remains also had a curved spine, in keeping with a tradition that Richard had a deformity that made him appear not to walk straight. In Shakespeare’s Tragedy of Richard III, he is portrayed as a “deform’d unfinish’d” villain.

“This is a historic moment and the history books will be rewritten,” said Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society, which originated the search. “We have searched for Richard and found him — now it is … time to honor him.”

Over the past months researchers poked and prodded the remains, subjecting them to CT scans, radio carbon dating, and DNA tests to confirm that they are indeed those of Richard III. Testing included a confirmed DNA match with samples from known living descendents of Richard III’s sister, Anne of York.

“The DNA sequence obtained from the Grey Friars skeletal remains was compared with the two maternal line relatives of Richard III,” explained Leicester University geneticist Turi King, and “we were very excited to find that there is a DNA match between the maternal DNA from the family of Richard III and the skeletal remains at the Grey Friars dig.”

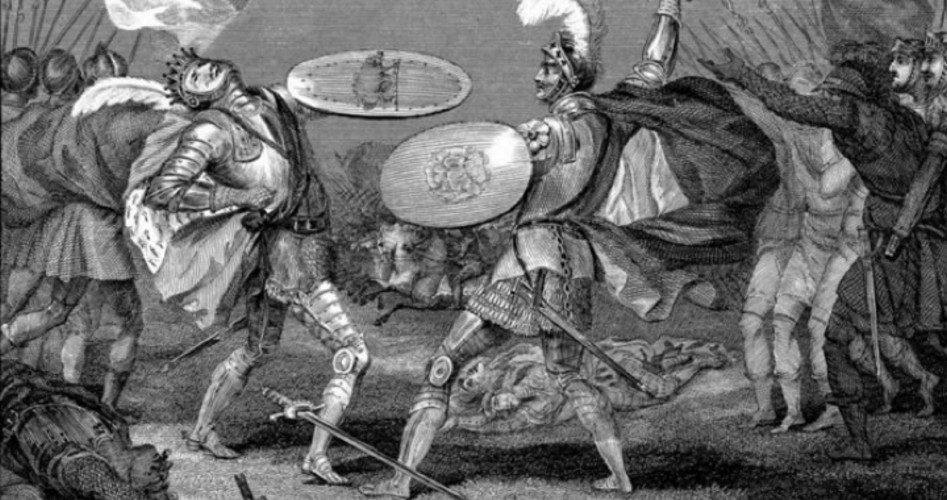

Expert analysis of the skeleton showed that it is consistent with the age and physique of Richard III as described in historical records, as well as with how the king is said to have perished. That includes a pair of wounds to the back of the skull that appear to have been made by a primitive weapon such as a sword or a battle ax used by warriors of the era. Historical accounts describe the king’s death at the Battle of Bosworth Field as coming from a blow to the back of the head.

There is also other damage to the skeleton’s ribs, the skull, and pelvis consistent with non-fatal wounds that may have happened in battle or after Richard was killed. “The skeleton has a number of unusual features,” said Jo Appleby, a university archeologist who examined the remains: “its slender build, the scoliosis, and the battle-related trauma. All these are highly consistent with the information that we have about Richard III in life and about the circumstances of his death. Taken as a whole, the skeletal evidence provides a highly convincing case for identification as Richard III.”

The Battle of Bosworth Field was the last major battle in the 30-year War of the Roses and Richard III was the final English king killed in battle. His death “brought about the end of three centuries of Plantagenet rule,” explained USA Today, “and ushered in the Tudors — starting with Henry VII and including Henry the VIII — who reigned for the next 117 years.”

Some historians and Richard III fans, such as the Richard III Society, insist that the king’s reputation as a usurper who did away with those who stood in his way to the throne — including two nephews locked up in the Tower of London and never seen again — is largely an inaccuracy based mostly on the literary and theatrical license of Shakespeare and Tudor historians who tried to destroy Richard’s reputation after his death. They note that his reign included some important reforms, including the introduction of the right to bail, along with the lifting of restrictions on books and printing presses.” Langley said that with the discovery of the remains, “a wind of change is blowing, one that will seek out the truth about the real Richard III.”

But in a column at CNN.com, English historian Dan Jones wrote that despite any reforms that King Richard III may have overseen, his actions in gaining the throne as the last of the Plantagenets was plainly criminal. “Richard did indeed usurp the crown…. He probably had his nephews killed, too; it is unknowable but overwhelmingly likely,” he speculated.

Those who think the discovery of his bones will help to rehabilitate Richard III’s reputation are in for a rude awakening, predicted Jones. “He usurped the crown from a 12-year-old boy, who later died,” wrote Jones. “This was his great crime, and there is no point denying it.” Likewise, he added, “it remains indisputably true that his usurpation threw English politics, painstakingly restored to some order in the 12 years before his crime, into a turmoil from which it did not fully recover for another two decades.”

The discovery of the monarch’s remains is doubtless newsworthy and exciting, but will do nothing to change the historical record, Jones predicted. While “Tudor historians and propagandists, culminating with Shakespeare, may have exaggerated his physical deformities and the horrors of Richard’s character,” wrote the historian, “… he remains a criminal king whose actions wrought havoc on his realm.”