Podcast: Play in new window | Download ()

Subscribe: Android | RSS | More

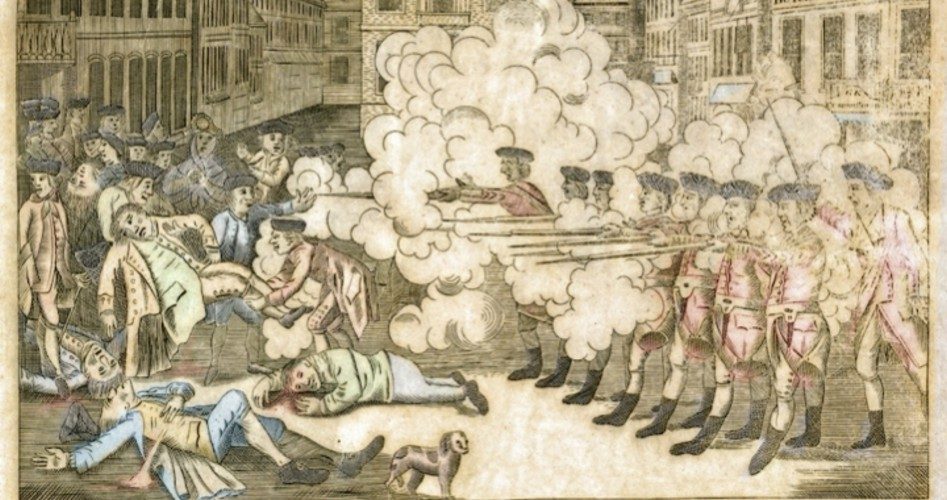

You can still see the spot. If you take the Freedom Trail tour in Boston, a uniformed park ranger will let you stand right on the spot where five Americans were killed by British soldiers on the night of March 5, 1770. This bloody encounter came to be known as “The Boston Massacre.” That fateful and fatal clash happened 250 years ago today.

However, the fuse that set off that powder keg was lit a couple of years before that night. Here’s the part of the story that is rarely told.

For years prior to the massacre, animosity toward the British by the colonists had been growing. The British wanted the colonists to help pay for the Seven Years’ War, a great deal of which consisted of England protecting its colonies from incursions from the French and their Native American allies, so the British taxed the colonists in various ways, starting with the Stamp Act, a tax on newspapers and legal and commercial documents. The taxes were unpopular.

In 1767, the passage by the English Parliament of the Townsend Acts, acts taxing glass, lead, paper, and tea (among other things), would lead to additional colonial discontent. The revenue generated by these taxes would be used to house British troops and to pay for the salaries and other maintenance of “civil government,” the representatives of the Crown that oversaw enforcement of regulations imposed on Boston by London. British troops had been stationed in Boston since 1768.

Both these groups were daily reminders to Bostonians that their natural right to govern themselves — a right they had exercised for nearly 150 years — was being denied them and that they were being treated as second-class citizens in the town and colony that they built.

In retaliation for acts of the British government that sought to transfer governing of the colonies from the people to the English Parliament — an act in open violation of Magna Carta — merchants in the Boston capital had united to refuse to purchase goods imported from England, called the nonimportation agreement.

Americans in Boston (and in other colonies who joined in the nonimportation alliance) did not take such tyranny lightly. As Englishmen they were born free, and Paragraph 63 of the Magna Carta guaranteed the enjoyment of their rights forever, regardless of where they lived:

IT IS ACCORDINGLY OUR WISH AND COMMAND that the English Church shall be free, and that men in our kingdom shall have and keep all these liberties, rights, and concessions, well and peaceably in their fullness and entirety for them and their heirs, of us and our heirs, in all things and all places for ever.

Those words meant something to the men in Boston who were being denied these “liberties, rights, and concessions.” Consequently, patriot leaders such as Samuel Adams and James Otis worked tirelessly and relentless to publicize and protest abuses of the British government in and around Boston.

At first, these abuses perpetrated by troops and by British government agents were reported in the pages of a weekly newspaper called the Boston Gazette. Upon seeing that the English had no intention of removing the troops and the troops had every intention of taking what they wanted from the townspeople, Adams, Otis, and other in the cadre of leaders of the patriot movement spread the news of these horrendous acts far and wide. An editor in New York named John Holt published the chronicle of British injustice in his own newspaper, the New York Journal, and then circulated it throughout the other colonies. The reports were eventually read by Americans in all 13 colonies.

In 1769, it was rumored that the English Parliament planned to pass a law amending the Massachusetts’ constitution, yet another tyrannical attempt to seize control of the colony and place its people under the command of an overreaching tyrant thousands of miles away.

Adams, Otis, and other members of the Sons of Liberty continued futilely pressing for the repeal of the Townsend Acts. In order to garner greater popular support for the patriot cause, the Sons of Liberty and others organized pro-liberty events throughout the city, celebrations marking the end of the Stamp Act, for example, where citizens would gather and toast liberty and declare their intention to protect their God-given rights against all who would dare deprive them of the same.

British officials and representatives of the Crown, including newly appointed Governor Thomas Hutchinson, were irritated by the agitation. They saw that every time they deployed British soldiers to enforce a law or control a demonstration, the crowds at the next demonstration even grew larger. These gatherings, Hutchinson declared in a letter to some Boston merchants, were “unlawful” and “evil” and would end up exposing the people and their assemblies to stricter control and harsher punishments for any man participating in such acts of “terror.”

“Never was the popular insolence at such a pitch,” wrote William Dalrymple, a British colonel and commander stationed in Boston. He was right. The British government’s insistence on depriving Massachusetts of self-government and the rights guaranteed them in the Magna Carta, as well the use of the money collected in taxes from the people of Boston themselves to house the soldiers and the tax collectors were pushing the people to the point of open revolt against such tyranny.

On February 22, 1770, a group of boys were carrying an effigy of the four loyalist Boston merchants who decided not to participate in the peaceful act of refusing to import British goods and were leading a group of protesters through the streets of Boston. The boys carried the effigy to the door of one of these dissenters. At this point, a man named Ebenezer Richardson — a man infamous in Boston for being not only a loyalist but an informer on all who tried to avoid paying taxes — yelled at the boys and the crowd that followed them and demanded that they give him the effigy and disperse.

Rather than obey this known turncoat, the assembled patriots chased Richardson to his house and began throwing rocks at it. Richardson ran inside his house, grabbed a rifle, and fired several shots into the crowd, killing 11-year-old Christopher Snider and wounding another young man of the same age.

There’s no need for a description of how the men and women of Boston reacted to the murder of this young boy. The four merchants who refused to participate in the nonimportation agreement left in a hurry. Richardson narrowly escaped being hanged on the spot by the men who watched him murder young Snider.

The Sons of Liberty organized a funeral for Christopher Snider, and the procession extended, according to most accounts, more than two miles. Snider was described in the patriot press as “the first whose life has been a victim to the cruelty and rage of oppressors!” The Boston Gazette declared that the blood “of young Snider … crieth for vengeance, like the blood of the righteous Abel.”

Within two weeks, British soldiers and the citizens of Boston were to have frequent clashes, as the former were placed throughout the city with orders to protect all agents of His Majesty, including customs officers, whom the Bostonians regarded as complicit in the murder of Christopher Snider.

When British officials in Boston complained that the people of Boston were harassing the troops, the Massachusetts Council advised that the enmity could be eased if commanders of the British army would withdraw the troops from the city. That advice was not taken and on March 5, 1770 the clashes would rise to a bloody crescendo.

Early on that day, British troops printed and posted a pamphlet insulting the people of Boston. Later, a soldier and a rope worker got in a fight. A small crowd assembled and a protest percolated and became a near riot.

As the sun set, a British soldier struck his apprentice with his musket for having the temerity to talk about the murder of Christopher Snider and to suggest that the boy would still be alive, but for the presence of the British army in Boston. Upon hearing of this abuse, a crowd of citizens gathered outside the living quarters of one of the army regiments in town and began throwing snowballs.

Soon, the bell rang signaling the beginning of a meeting, and a large group of Bostonians gathered outside the custom house where most of the British soldiers were posted. Someone in the crowd recognized the soldier who hit the apprentice and called it out to the crowd and immediately the protestors began pelting the garrison with icicles and snowballs.

As the crowd continued throwing snow and ice at the soldier identified as the one who struck his young apprentice, the customs officials sent word to the commander of the main guard, Captain Thomas Preston, to come to aid of his companions stationed at the customs house, and to defend the representatives of the Crown, whose will and reports had brought the British army to occupy Boston.

Captain Preston arrived with a cohort of seven men, and they began to work their way through the crowd by pushing people out of the way with the point of their bayonets. By this time the citizens were so filled with indignation and courage that they refused to be moved, despite being prodded by bayonets.

As they moved through the tightly packed protestors, the gun of one of the British soldiers was dropped and the troops opened fire on the crowd. From the second floor of the customs house, customs officers began firing, as well, taking advantage of the opportunity to shoot citizens without fear of reprisal.

When the smoke cleared, five men were dead or nearly so, and six others were wounded. Nearly immediately, the attack became known as “The Boston Massacre” and news of the deadly clash spread quickly throughout Massachusetts and the rest of the colonies.

Among the dead was a black sailor named Crispus Attucks. He was an active member of the Sons of Liberty, and now his life was taken from him by the standing army he spoke out so forcefully against.

The gunfire caused the crowd to disperse, but after the shooting ended, the men returned to carry away the dead and the wounded. The soldiers raised their weapons to fire again, but Captain Preston ordered them to stand down and, in fact, knocked their weapons out of position. It was too late. The shots had been fired and the flames of resistance had been fanned.

Upon hearing the ruckus, men and women began crowding into the streets of Boston shouting “To Arms!” “To Arms!” All told, almost 500 Bostonians took to the streets that night, determined to deal justice to the killers and once and for all to rid themselves of the British army of occupation that had terrorized their city for two years.

Preston, savvy enough to see how such an encounter would end, led his squad in a hasty retreat back to the guard house. The deed was done, and the people would no longer be silenced or intimidated by the superior arms of the standing army that occupied their city.

The next day, the people of Boston would show up en masse to protest the armed assault by British regular soldiers on the people of Boston. Here’s the story as summarized in an article published by the University of Missouri at Kansas City:

On March 6, 1770, the day after the shootings, Samuel Adams was chosen by a citizens group gathered in Faneuil Hall to chair a committee of fifteen that would petition Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson for the “immediate removal of troops” from the city of Boston. When Hutchinson suggested that he lacked the authority to order the removal of troops, Adams responded: “Sir, if the Lieutenant Governor or Colonel Dalrymple, or both together, have the authority to remove one regiment, they have the authority to remove two, and nothing short of a total evacuation of the town, by all regular troops, will satisfy the public mind or preserve the peace.” Adams wrote that as he made his demands to Hutchinson, “I thought I saw his face grow pale, and I enjoyed the sight.” Adams would have his way: two British regiments (jokingly called “Sam Adams’ two regiments”) sailed from the city to Castle William.

Later, Adams would continue his defense of liberty and his opposition to occupation by the army in writing. When in response to an essay Adams penned someone claimed that Crispus Attucks was carrying a club and therefore the soldiers were justified in shooting him, Adams wrote that Crispus Attucks “had as good a right to carry a stick, even a bludgeon, as the soldier who shot him had to be armed with musket and ball.”

And there’s the rub. There are those to this day who claim that the citizens of Boston had no right to throw snowballs at the soldiers or to carry clubs to the demonstration, while ignoring that the greater evil was the fact that British soldiers were occupying Boston and abusing their authority all while being funded by taxes unconstitutionally imposed on the people of Boston.

People who say there would have been no “Boston Massacre” had the colonists not reacted violently to the actions of the British army, forget that there would have been no reaction on the part of colonists at all had the British army not been occupying the formerly free city of Boston in defiance of Magna Carta and the natural rights of all men to govern themselves.

Image of Boston Massacre: Keith Lance / DigitalVision Vectors / Getty Images Plus