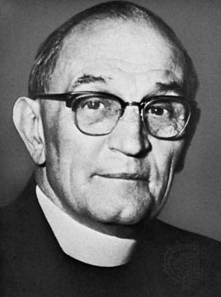

On July 1, 1937, 75 years ago, the utter incompatibility of Christianity with Nazi totalitarianism was made clear to the world when Protestant Bishop Martin Niemöeller, a U-boat captain and hero during WWI, was arrested by the Gestapo for his sermons against Nazi sins manifested in brutal torture, euthanasia, anti-Semitism, and paganism. Because of the bishop’s fame as a war hero, the Nazis would have been happy to have given him a high position in their Nazified “German Christian Church”; however, he — like so many thousand other lesser-known German ministers and priests — refused the easy path and thus was consigned to the dark realms of Nazi brutality. Niemöeller eventually endured seven long years of solitary confinement in a prison camp.

Though the Nazis came to national power in 1933, they had gained control of state governments as early as 1930. What did they do with that power? In his 1940 book Hitler’s 12 Apostles, Oswald Dutch recalls of senior Nazi party official Wilhelm Frick: “Whoever in 1930 observed Dr. Frick’s official activities could have had a foretaste of National Socialist government. The first thing he did was to abolish religious prayer in school.” As soon as the Nazis gained power anywhere, they began to suppress Christianity.

The rhetoric of the Nazis matched their conduct. In 1932, before his ascension to power, Hitler declared: “We are not against the hundred and one different kinds of Christianity, but against Christianity itself.” Authors of books written at the time noted the same hatred of Christianity expressed by Hitler before the Nazis came to power in 1933. Arthur Duncan-Jones quoted Hitler expressing his attitude toward Christianity even before he gained power: “I insist on the certainty that sooner or later, once we hold power, Christianity will be overcome. Of course, I myself am a heathen to the bone.” Alfred Nestor recorded these words from Hitler’s mouth, long before Hitler took control: “We shall work towards replacing the cross of Christ with the cross of loyalty to our party, the Swastika,” and “We must conduct war — not against this religion or that religion — but against all of Christianity.”

Leo Stein, who was at the brutal concentration camp Dachau with Niemöeller, recorded from the pastor the utter antipathy with Christianity that Hitler presented almost as soon as he came to power. In Stein’s book I Was in Hell with Niemöeller, he relates what Hitler told the famous pastor: “Jesus Christ was only a man, and a Jew to boot.” The Führer went on to describe Christianity as a sort of “mental illness.”

The Nazis began a steady process of what many writers at the time called the “de-Christianization of Nazi Germany,” directed at Protestants and Catholics alike. The Confessional Church which broke off from the traditional Protestant church in Germany was headed by Niemöeller. These clergymen were relentless in their resistance to Nazism. The Confessional Synod in June, 1935, unanimously passed a resolution in favor of continuing the struggle against the Reich bishop. That August the bishops of Germany presented at Fulda a pastoral letter warning of the Nazi “campaign of annihilation against Christianity,” and the same month, SA (stormtrooper) members in the Rhön district were punished by an SA officer for the “crime” of attending church.

The Confessional groups of Christians — Protestants who had refused to join the “German Christian” movement — sent Hitler a letter in May of 1936 asking whether he intended to “de-Christianize the German people.” The response was wholly unsatisfactory, with the Christian clergy believing that Hitler had accepted “honors due only to God.” In July of the same year, a manifesto was read in thousands of churches: “Things have come to pass that the honor of German citizens is being dragged through the mud because they are Christians … They are jeered at and mocked at in every way (press, theatre, lectures, mass meetings) because their faith is in Jesus Christ … Those who firmly cling to the Gospel are specially suspected in these respects.” The same year, Rom Landau wrote: “We have it from the Führer’s own lips that ‘to-day the Christian era is replaced by the National Socialist Era.’”

By 1937 death notices in Germany began stating that the decedents “died in the faith of Adolph Hitler” or, as another writer put it, “in place of the customary phrase ‘died with belief in God,’ is used the formula, ‘died with belief in Adolf Hitler,’ or ‘Died with belief in his Führer.’” In June of 1937, the month before Niemöeller was arrested, all representatives of the Confessing Church had their passports confiscated by the Gestapo.

The hostility of Nazis towards Christianity was intense, but Christians such as Bishop Niemöeller were not passive. They recognized the evil of Nazism and early on condemned it in unequivocal terms. In November of 1934, 20,000 Christians in Germany turned out to hear Niemöeller denounce Nazi racial policies. Father Viktor Koch told the assemblage, “We are fighting against the defamation of Christ and true Christianity. There are false prophets abroad in this land preaching the doctrine of blood and soil and racial mysticism, which we denounce.” At the end of the meeting, Niemöeller stated, “For us, it is a question of which master German Protestants are going to serve: Christ or another.”

Olive Wyon, in her introduction to A Lutheran in the Weimar Republic, Hanns Lilje’s inspiring story of his survival as a Christian clergyman held for years by the Gestapo, notes: “The Churches were the first groups to show the National Socialist government that there were limits to the brutal exercise of power…. Priests and pastors were in the foreground of the conflict. They suffered severely and heroically.” Paul Means noted in his 1935 book Things That Are Caesar’s: “It is significant that the first organized protest and the first effective response to Nazi racial doctrines came not from German science or philosophy but from zealous groups bent on maintaining the purity of the Gospel within the German Church. The prophetic voice in the church, Catholic and Protestant, could not be silenced.” The same year, Philip Dorf, in his textbook Europe at the Crossroads, saw exactly the same thing: “German politics, industry, finance, labor, and culture submitted meekly to the imprint of the swastika. Only in the field of religion did the principle of the totalitarian state encounter any serious resistance.”

Seventy-five years ago, the courage of Christian conscience in Germany resisted godless totalitarianism as it has so often in the last century (and does today). Although Martin Niemöller would up in Dachau, as Leo Stein noted in his book, all the bishop would have had to do to be freed was promise to cooperate with the Nazis. He did not.

Niemöller was not the perfect hero for many. He was a pacifist during the Cold War whose conduct earned him the dubious honor of the Lenin Peace Prize and the equally dubious honor in 1961 of being president of the World Council of Churches. But 75 years ago, when his faith was on the line, Niemöller was on the side of the Lord Jesus Christ, as were so many other martyred German pastors and priests who suffered at the hands of the Gestapo and SS, and who died rather than abandon the clear demands of their Christian faith.

Photo: Bishop Martin Niemöeller