“All of the ages of the world have not produced a greater statesman and philosopher united than Cicero.”

— John Adams, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America

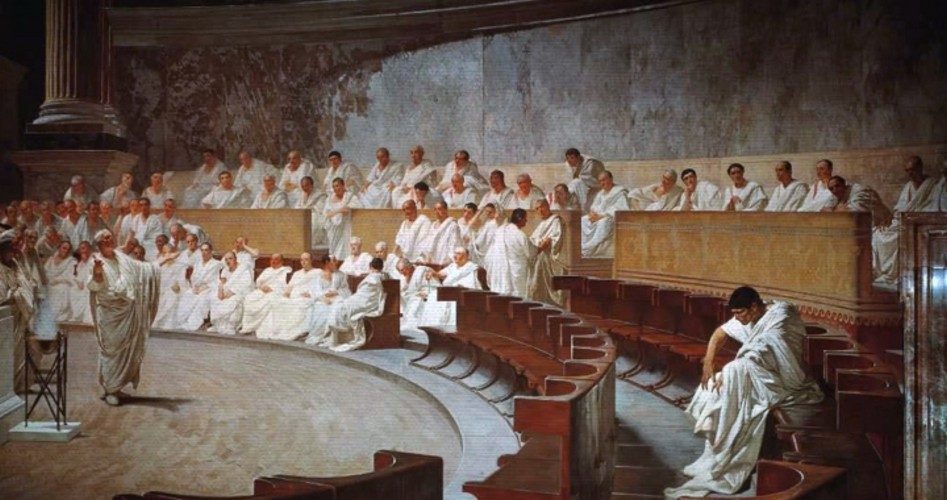

“Did the Roman people elect us so that, having been granted so high a position, we should consider the Republic as nothing?” Cicero asked in the first of 14 speeches against the tyranny of Marcus Antonius, known to history as Mark Antony.

Together, these speeches are known as the Phillipics (or Philippicae), named after similar discourses against despotism delivered centuries earlier in Athens by Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedon (father of Alexander the Great).

On September 2, 44 B.C., Cicero returned to Rome and addressed the Senate, moved to speak boldly against the attempt by Mark Antony to take advantage of a crisis to seize unconstitutional power over Rome.

Calling themselves liberators, several senators rose up against Julius Caesar, who had declared himself dictator for life. On March 15 — the famed Ides of March — they assassinated Caesar, believing the people of Rome would cheer their act and celebrate their freedom from tyranny.

The people of Rome, stoked into anger by Mark Antony, chased the liberators out of town and praised Julius Caesar as a martyr and a god. Antony took advantage of this fervor and confusion to consolidate power.

Recognizing the danger of opposing a man who appeared to have such strong popular support, most senators meekly sidestepped their responsibility to preserve, protect, and defend the constitution of Rome.

Cue Cicero.

Cicero cut short a trip to Athens to return to Rome and address the Senate, chastising them for their feckless retreat from their role as defenders of the constitution.

“You had to do something; I feel sorrow that the Roman people are beginning to think you men were afraid to live up to your position (which itself would be shameful) but because you all did so for different and individual reasons,” Cicero declared.

Fearlessly, Cicero stood in the Senate calling out the co-conspirators — not those who killed Caesar, but those who through their silence were helping Mark Antony assassinate the Roman constitution.

“You should be men who thought not about what you could do for the Republic, but what you personally ought to do,” Cicero challenged.

Cicero then goes on to recount why he returned to Rome, before even reaching Greece.

“I was fixed with such eagerness to return that no oar, no winds were swift enough to keep me from arriving in time to assure that the state might suffer no greater harm from any delay,” Cicero said.

On his way back to Rome, Cicero ran into Brutus, one of the leaders of the liberators who assassinated Caesar, and Brutus explained to his former colleague that he and his fellow assassins had been chased out of Rome by a populace primed to avenge the murder of Caesar.

Upon hearing Brutus’s story, Cicero lamented the fact that the Romans had become people addicted to entertainment and government handouts and driven to murderous rage by the death of a tyrant and of their rights as freemen.

“For pity’s sake, what is this voluntary slavery?” Cicero asked, days later during his first Philippic. He could not believe that there was no one in the Senate and so few citizens of Rome willing to “do anything” in defense of their liberty and in opposition to the autocracy established by Caesar and being perpetuated by Antony and others.

Then, with a flourish, Cicero crescendoed to the end of his speech, calling out Mark Antony for his personal crimes against the constitution of Rome and the liberty of its people.

“Blind to glory’s true path, you think it glorious to possess by yourself more power than all others and to be feared by your fellow citizens,” Cicero asked the absent Antony.

Cicero followed that observation with a reminder of what it truly means to be a statesman.

“To be a citizen dear to all, to deserve well of the state, to be praised, courted, and loved is glorious. But to be feared and to be an object of hatred is invidious, detestable, and proof of weakness and decay,” he added.

Mark Antony, though not present to hear Cicero speak, was informed of Cicero’s assault on his character and his acts against the liberty, peace, and prosperity of the Roman people. Antony, Cicero believed, would not allow these remarks to go unchallenged. Cicero feared he would be killed by Antony or his advocates before he was able to speak again.

“Should my life be lengthened,” Cicero said at the close of his speech, anticipating Antony’s revenge for his words, “it will be lengthened not for myself, but for my fellow citizens and for the republic.”

It would be more than a month before Cicero would deliver his Second Philippic, and in that follow-up speech he would point out how because of the fraud, deceit, and force of Antony and many of those elected to protect the constitution, that the constitution was lying there on floor of the Senate, stabbed by conspirators, just as had been the body of Julius Caesar. Cicero would reveal in this speech, though, that certain members of the government intended to kill him, too. He knew that several of those would-be murderers were seated there in the Senate, squirming as they heard him call out their conspiracy.

We will follow the Philippics as we celebrate the days they were delivered. The purpose is that, as Cicero wrote, “History is the light of truth,” and by that light we might illuminate our own times and avoid walking the trail to totalitarianism walked by Rome.

Image: Cicero Denounces Catiline/Public Domain

Joe Wolverton II, J.D., is the author of the book The Real James Madison, What Degree of Madness: Madison’s Method to Make America STATES Again, and The Founders Recipe. He hosts the YouTube channel “Teacher of Liberty” and the podcast of the same name.