Canada’s Quebec province is considering a law that would make it illegal for public employees to wear religious headwear such as Muslim burqas and Jewish skull caps (kippas), along with prominently displayed religious symbols such as crucifixes. The proposal mirrors a law passed in France in 2010 that effectively banned Muslim women from wearing burqas in public. Some observers suggest the proposed legislation is part of a push by separatist-minded French Quebec to move toward total independence from the rest of Canada.

The minority Parti Quebecois, which is behind the proposal, says that the law would treat everybody equally by eliminating special clothing privileges for certain individuals in the public workplace, and allow other employers to set limits on employees’ religious practices, such as prayer times, that interfere with business. They point out that the law would discourage the wearing of clothing such as burqas which, they insist, cultivates discrimination against women.

“We want rights and values that will be the source of harmony and cohesion,” Bernard Drainville, Quebec’s minister of democratic institutions and active citizenship, was quoted by the Wall Street Journal as saying of the proposed law. “That will apply to all Quebecers, regardless of our faith and religion.”

Opponents of the measure argue that it is a blatant attack on religious freedoms and cultural minorities, with Muslims and Jews insisting that the proposed law specifically targets them and their unique worship practices.

“This is painful; it’s an encroachment on freedoms that are guaranteed constitutionally,” said Salam Elmenyawi, head of the Muslim Council of Montreal.

Harvey Levine, president of the Quebec branch of B’nai Brith, an international Jewish organization, agreed, charging that “they’re trying to remove religious freedoms. They’re trying to impose rules on religious values.”

Luciano Del Negro of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs in Quebec noted that “the Jewish community has been in Quebec for 250 years. Now, if you wear a kippa, you will have to choose between religious observance and a job in the Quebec public service.”

Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper quoted Khadija Darid, director of Espace Féminin Arabe, as saying that the proposed law “is extremely discriminatory and essentially targets Muslim women. These women chose Quebec and Canada for its freedoms. Now, everything is being cut.” She noted that Quebec welcomed Muslim immigrants from French-speaking North Africa, and is now making their lives unnecessarily difficult. “A lot of women are telling me they will leave Quebec,” she said.

The Globe and Mail quoted one Muslim woman, 38-year-old Samah Tliba, 38, who came to Quebec from Algeria. “I love Montreal,” she said. “I came here because it was an open place, and it felt like home. I’m not so sure now. I have a sister in Toronto; I think I’ll move there.”

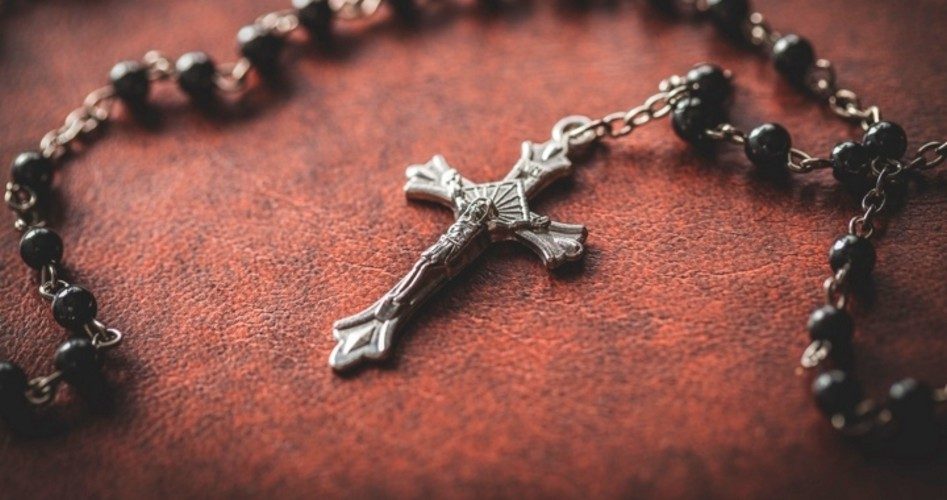

Additionally, Christians expressed their concern that such a law would be used, as it has been in the U.K., to ban the wearing of all crosses and Christian symbols. According to the BBC, while banning larger crosses and Christian symbols, the law “would allow public workers to wear discreet religious symbols including small crucifixes or a Jewish Star of David.”

Some Christians in the Canadian province said the government has no right to determine what they can or cannot wear relative to expressing their faith. “If you want to wear a cross on your neck, that’s your business,” said an official with a union representing Quebec teachers. “Just as long as you don’t talk about the crucifixion in class.”

Drainville insisted that under Quebec law, public workers must remain as secular as the government that employs them. “That’s why the government of Quebec is proposing to ban public employees from wearing ostentatious religious symbols during work hours,” he told reporters. “We’re talking about very obvious symbols … which send a clear message: ‘I am a believer and this is my religion.’”

But according to the Montreal Gazette, Drainville thinks the law will also impact the policies guiding private businesses in Quebec. “We think private enterprise will effectively be guided in the future by the guidelines we are giving ourselves,” he said. “There are many employers who are scared to find themselves in the face of requests for reasonable accommodations, and we are responding to these fears.”

Observers have noted that Quebec’s push toward a secular society over the past several decades has been notably aggressive. “Until the early 1960s, Quebec was heavily dominated by a Roman Catholic church that ran the health-care and education systems and wielded huge influence over public and private life,” recalled Reuters News. “Over the next decade, a new generation of politicians, frustrated by what they saw as the stifling influence of the church, pushed through reforms that stripped it of much of its influence. ‘The rate of change has been astounding,’ said Pierre Martin, a politics professor at the University of Montreal.”

As for separatist notions in the province, Reuters noted that the changes of the 1960s “helped create the separatist Parti Quebecois, which wants Quebec to break away from the rest of Canada. Separatist governments have held two referendums on independence, in 1980 and 1995. Both failed.”

The Montreal Gazette noted that if passed, the law will initially continue to allow such religious symbols “as the crucifix over the speaker’s chair of the National Assembly to remain as well as the cross atop Mount Royal.” Additionally, in contrast to some government entities in the United States, public workers will still be allowed to display Christmas trees, though nativity scenes may be a stretch.

However, noted the Gazette, “it will be up to the courts to decide if witnesses will still swear to tell ‘the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth,’ by holding their hand on the Bible.”