When defense counsel for James Holmes, the alleged Aurora, Colorado shooter, said on Monday that Holmes was not ready to enter a plea in his murder trial, Arapahoe County District Court Judge William Sylvester entered one for him: not guilty. The judge also said Holmes could change that plea to not guilty by reason of insanity, but if he did, Holmes would be required to submit to a “narcoanalytic interview” using “medically appropriate” drugs to determine if he really was insane at the time of the shooting or if he was just faking it.

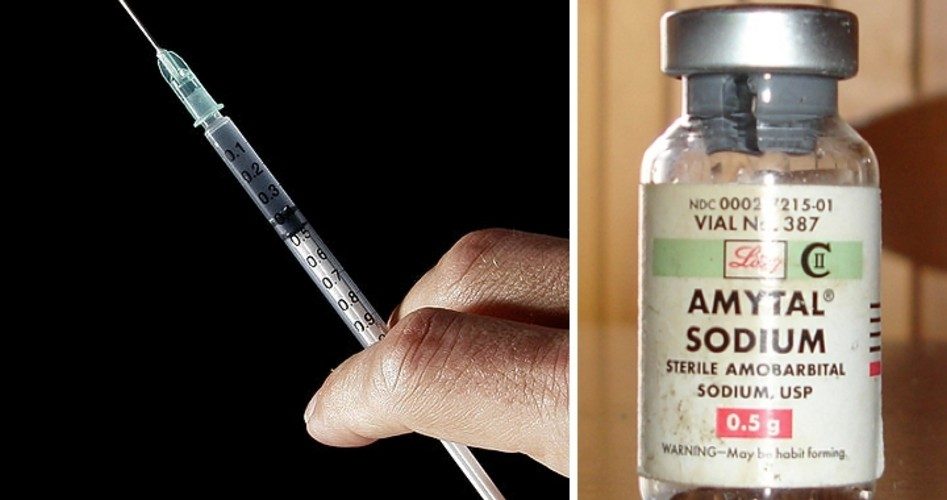

Truth serums have a lurid history, and their effectiveness in rooting out truth has been seriously questioned. Use of them raises serious legal, ethical, and constitutional questions, as well. Scopolamine, sodium pentathol, and Amytal are the drugs most commonly used in such interviews, as they cause the patient (in this case, the defendant) to become uninhibited and talkative, but according to the Gale Encyclopedia, they “do not guarantee the veracity of the subject.… Persons under the influence of truth serums are still able to lie and even to fantasize.”

The procedure involves injecting Holmes with gradual doses of the drug until he relaxes and becomes more open to questioning. August Piper, a Seattle-based psychiatrist who has used truth serum in treating patients, explained how it works:

During an Amytal interview, the physician administers small amounts of the drug, by vein, every few minutes. The procedure usually takes about an hour. The patient is drowsy and slurred of speech, but awake — the so-called “twilight state” for the duration of the interview.

Intravenous Amytal causes a feeling of relaxation, warmth, and closeness to the interviewer; while in this state, the patient is questioned.

However, the answers to those questions may not be useful or even legal in court. Piper said that all this does is “lower the [patient’s] threshold for reporting virtually all information, both true and false.”

William Shephard, chairman of the criminal justice section of the American Bar Association, said that using a truth serum to prove a defendant’s claim that he was insane at the time of the shooting would be highly unusual and would provoke other problems as well:

If a defendant loses his right to remain silent because the court has authorized the use of drugs that make him talk, that would raise all sorts of Fifth Amendment issues that both sides would have to address.

The Supreme Court has already ruled that a confession resulting from the use of drugs is inadmissible in court. In Townsend v. Sain, Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren wrote the majority opinion:

Numerous decisions of this Court have established the standards governing the admissibility of confessions into evidence. If an individual’s “will was overborne” or if his confession was not “the product of a rational intellect and a free will,” his confession is inadmissible because [it was] coerced. These standards are applicable whether a confession is the product of physical intimidation or psychological pressure and, of course, are equally applicable to a drug-induced statement.

It is difficult to imagine a situation in which a confession would be less the product of a free intellect, less voluntary, than when brought about by a drug having the effect of a “truth serum….”

Any questioning by police officers which in fact produces a confession which is not the product of a free intellect renders that confession inadmissible.

But that case may not apply, as Judge Sylvester isn’t seeking a confession but rather a determination that Holmes was, or wasn’t, insane at the time of the shooting.

If Holmes decides to enter a plea of not guilty, then he has an equally difficult task of proving his innocence in the shooting, which took the lives of 12 people and injured 58 more. The prosecution will present evidence that he planned the massacre well in advance, that he ordered ammunition through the Internet, and purchased firearms on separate occasions at different stores, dressed in paramilitary gear, and installed a highly sophisticated series of explosive devices in his apartment to be triggered by anyone opening the door. Holmes is facing 166 counts of murder and manslaughter in the case.

Aside from the legal, ethical, and constitutional questions surrounding the use of a “truth serum” to determine if Holmes was insane or not at the time of the shooting, there are other questions that may never be answered. Did the drugs he was taking at the time of the shooting have anything to do with his behavior, both during and after the incident? What would explain his odd behavior at his pre-trial hearing, with his flaming red hair and distant robotic look? Did he have outside help? What would explain the statements by witnesses that he had help holding the door to the theater and throwing tear gas canisters into the audience? Where did he get the estimated $20,000 to fund his purchases? He was, after all, a poor college student. Who taught him how to rig the explosives in his apartment? Was this a setup with help from the FBI, as some have asked?

There is at least one certainty: Holmes’ Sixth Amendment right “to a speedy and public trial” will be further abrogated as the issue of the efficacy and legality of administering a truth serum to ferret out the truth will likely be long and drawn out.

A graduate of Cornell University and a former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American and blogs frequently at www.LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].