“I don’t deny your right to believe whatever you’d like; but I have the right to point out it’s ignorant and dangerous for as long as your baseless superstitions keep killing people.”

Craig Stephen Hicks may or may not embrace “baseless superstitions,” as he characterized religious faith in the above statement at the top of his Facebook page. The 46-year-old Chapel Hill resident nonetheless killed three people Tuesday in an act that may be what authorities call a “hate crime” or simply a dispute over noise and parking at his condominium complex.

Hicks’ ex-wife, Cynthia Hurley, said the self-described “gun-toting” atheist exhibited “no compassion at all” for other people, and, writes the AP, “A woman who lives near the scene described Hicks as short-tempered. ‘Anytime that I saw him or saw interaction with him or friends or anyone in the parking lot or myself, he was angry,’ Samantha Maness said of Hicks. ‘He was very angry, anytime I saw him.’” And on Tuesday, it appears, the North Carolina man exploded, shooting to death Deah Shaddy Barakat, 23; his wife, Yusor Mohammad, 21; and her sister Razan Mohammad Abu-Salha, 19. All three victims were Muslim.

Hicks’ current wife, Karen Hicks, said the murders were “related to long-standing parking disputes my husband had with various neighbors…, had nothing [to] do with religion or the victims’ faith” and that her husband “champions the rights of others,” reports the AP.

Nevertheless, the murdered sisters’ father, psychiatrist Mohammad Abu-Salha, insists the act was a “hate crime.” The AP quotes him as saying, “The media here bombards the American citizen with Islamic, Islamic, Islamic terrorism and makes people here scared of us and hate us and want us out. So if somebody has any conflict with you, and they already hate you, you get a bullet in the head.”

And while many others also blame anti-Muslim rhetoric — with some social-media users posting crime information with the hashtag “#MuslimLivesMatter” — this analysis perhaps ignores Hicks’ ideological/philosophical profile.

Hicks’ Facebook page is thoroughly devoted to opposition to religion in general. In fact, above the statement of his cited at this article’s opening, he expresses the sentiment “Of course I want religion to go away.” Below it he wrote, “ANTI-THEISM: The conscientious objection to religion” and “Atheism 411.” “Anti-theism” is the term apparently coined by late writer Christopher Hitchens — who penned the book God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything — and refers to not just disbelief in God but active opposition to faith (usually accompanied by hostility). Hicks’ Facebook page also bears the logo of “Atheists for Equality” in the upper-left-hand corner, and the Independent tells us, “TV programmes liked by Hicks include The Atheist Experience, Criminal Minds and Friends, while he describes himself as a fan of Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason and Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion.”

This brings us to what some might call the Hate Crime Delusion. It’s hard to imagine any crime, at least one deserving the designation, that’s an act of love. Yet not all criminals are prosecuted for hatred. And it seems the always “very angry” Hicks was certainly filled with hate. Yet should he be prosecuted for a “hate crime,” it won’t simply be because he hated. It will be because he hated the wrong people.

It’s absolutely possible that ever-hostile Hicks, who had “no compassion at all” for others, was a misanthrope; in other words, a hater of humans. And while this group certainly enjoys legal protection relative to cows, horses, or aardvarks (despite PETA’s best efforts), it doesn’t qualify as a “protected class” under hate-crime law. For that the group must be a subset of humans — the right subset.

In North Carolina this means, a state government website tells us, a class defined by “race, color, religion, nationality, or country of origin” but not, as yet, by “sexual orientation, gender or disability.” And if you’re a crime victim and you make the protected-class cut, your victimizer will suffer, as the state puts it, “penalty enhancement.” If you don’t, you’ll have to settle for your victimizer getting an unenhanced penalty.

What this means for Mr. Hicks is unclear. If it’s determined he committed his murders not because he hated Muslims in particular but “religious” people in general, will he suffer enhancement? Or are religionists too generic? For sure, enhancement won’t be deemed necessary if he’s an equal-opportunity hater, a mere human-despising reverse speciesist. (The same is true for unprotected subsets. Killing people because they’re Republicans, Democrats, conservatives, liberals, gluttons, smokers, or Phillies fans also isn’t considered enhancement-worthy.)

Then, even if it was friction over parking that finally set Hicks off, is it possible he might have been more amicably disposed toward the victims if they’d been fellow atheists? Could this have had a subconscious effect? Since the government has appointed itself arbiter of not only the acceptability of thoughts but also their existence, it has its work cut out for it. And perhaps science can help. It has already developed a primitive mind-reading device, and maybe future innovations will take all the guesswork out of who needs a good enhancin’.

Of course, some deny that hate-crime laws are an effort at thought control. Others ask: If two crimes are committed and are identical in terms of the acts themselves, but one is deemed to warrant more punishment, what could the extra punishment be for other than the thoughts expressed through the act? Many citizens still consider this un-American and believe we should punish behavior, not beliefs. They might point out that, traditionally, intention was considered during prosecution only insofar as it was a mitigating factor (e.g., self-defense, jealous rage), not an aggravating one.

Some critics might conclude that hate-crime law itself is driven by prejudice, by a desire to punish certain people and thoughts — while offering special protection to other people — based on a politically correct code of values. After all, hate (wrath) is just one of the Seven Deadly Sins, which also include sloth, gluttony, pride, envy, lust, and greed. Is it possible our focus on wrath is a tad gratuitous? Note, the Bible tells us that “the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil,” and most crimes are driven by greed.

Of course, there is a solution here: Apply enhanced hate-crime punishments to all crime — and then eliminate the hate-crime category. For if the increased punishment serves as a greater deterrent to, let’s say, murder, shouldn’t we want to deter all murder? Barring this, every politician who supports hate-crime law should have to meet monthly with the loved ones of a non-hate-crime murder victim and explain, face-to-face, why his killer deserved less punishment. It just might induce an epiphany in some legislators’ craniums.

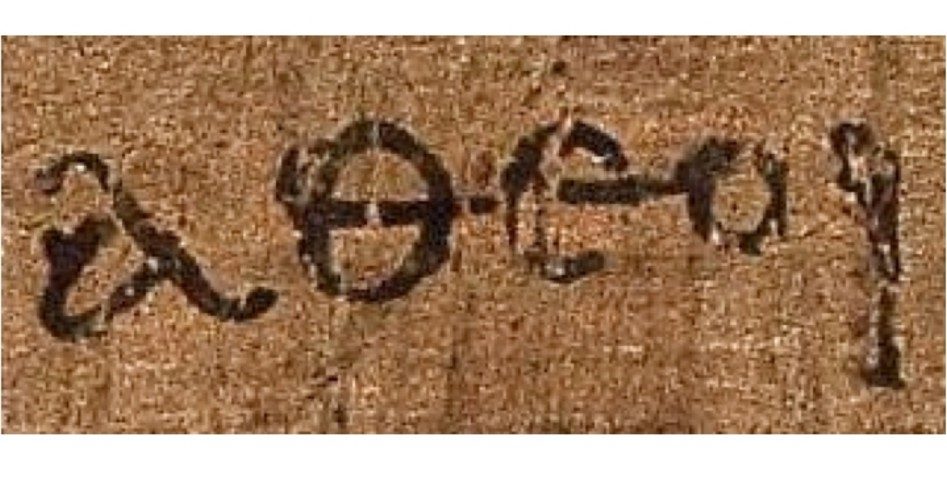

Photo is of ancient Greek word that means “without God”