In 2006, Jeffrey Stoleson, a sergeant in the Army Reserve then in Iraq, described an unbelievable scene to reporter Frank Main of the Chicago Sun-Times. Based on Stoleson’s account, and the many pictures he had taken, Main wrote: "In a storage yard in Taji, about 18 miles north of Baghdad, dozens of tanks were vandalized with painted gang signs…. Much of the graffiti was by Chicago based gangs," according to Stoleson.

Since then, Congress has banned members of the military from being in street gangs, and the Defense Department put the ban in its rulebooks last November. But that hasn’t slowed down the apparent growth of gang activity inside the military. According to Stoleson and others, it has only gotten worse.

Stoleson, described by Main as a "Wisconsin corrections officer" when not serving as a sergeant with the National Guard, returned home from his latest tour in Iraq in January, where he worked with the Army to set up a prison facility near Baghdad. As before, he said the signs of gang activity were all around.

"I saw Maniac Latin Disciples graffiti out of Chicago," he told Main. According to Main’s report, Stoleson also saw "a lot of graffiti for Texas and California gangs, as well as Mexican drug cartels."

An unnamed Chicago Police officer, who Main says "retired from the regular Army and was recently on a tour of Afghanistan in the Army Reserve" echoed Stoleson’s comments. Noting that Bagram Air Base was covered in Chicago gang graffiti, the officer said the problem "seems bigger now."

The Police officer, who described gang activity in the military as "scary," told the Sun-Times that "he has arrested high-level gang members who have served in the military and kept the ‘infantryman’s bible’ — called the FM 7-8 — in their homes." That book, Main notes, "describes how to run for cover [and] fire a weapon tactically."

But gang members with military experience often have more to rely on than a printed "how-to" manual for warfare. "Gang members are coming home now with one or two tours," Stoleson said. "Some were on the field of battle."

Once back on the streets domestically, militarized gangsters can present an even greater threat to civilians and law-enforcement personnel.

A tragic and deadly example of the potential danger posed by militarized gang members is the ambush of police officers in Ceres, California, in 2005. Hoping to lure officers into his trap, at approximately 8 p.m. on January 9 of that year, Lance Corporal Andres Raya fired his assault rifle in front of a liquor store. Going inside the store, he told the clerk that he had just been shot at, and asked that the police be called. Raya then waited for the police to arrive. He then shot and killed police Sergeant Howard Stevenson, and seriously wounded officer Sam Ryno. Stevenson’s death, in particular, was essentially an execution. Having wounded the officer, Raya ran to him and ended his life with two shots in the back of the head.

It was later determined that Raya was a gang member. A January 14, 2005 press release from the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Department noted: "Authorities have discovered information during the investigation into the Ceres Police Shooting that shows Andres Raya was a Norteño gang member." They also discovered a video tape belonging to Raya that had been seized on December 28 following a burglary at the Ceres High School. According to the Sheriff’s Department: "The videotape shows Raya smoking what appears to be marijuana in several different clips, ‘throwing’ gang signs, and showing gang graffiti while bragging that he wrote it. It also showed a United States flag that had been cut up and arranged on the high school gymnasium floor to spell out ‘F… Bush’."

It was later determined that Raya was a gang member. A January 14, 2005 press release from the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Department noted: "Authorities have discovered information during the investigation into the Ceres Police Shooting that shows Andres Raya was a Norteño gang member." They also discovered a video tape belonging to Raya that had been seized on December 28 following a burglary at the Ceres High School. According to the Sheriff’s Department: "The videotape shows Raya smoking what appears to be marijuana in several different clips, ‘throwing’ gang signs, and showing gang graffiti while bragging that he wrote it. It also showed a United States flag that had been cut up and arranged on the high school gymnasium floor to spell out ‘F… Bush’."

Raya’s attack on police in Ceres was exceptional for its violence, but militarized gang members have been involved in several crimes. Sun-Times reporter Frank Main said that another unnamed Chicago police officer "who searches homes for drugs and guns, said gang members targeted by his team are sometimes current or former members of the armed forces." That officer told Main: "We recently arrested a guy in the reserves for crack [cocaine]. He was a gang-banger."

In fact, as recently as 2007, a multi-agency federal law enforcement task force reported that some gang members known to have committed crimes were being recruited. The report titled "Gang-Related Activity in the US Armed Forces Increasing," dated January 12, 2007 and prepared by the National Gang Intelligence Center (NGIC) found that "US criminal courts have allowed gang members to enter the service as an alternative to incarceration. Several incidences wherein gang members have been recruited into the armed services while facing criminal charges or on probation or parole have been documented."

In one such case, the report found that in 2005 "a Latin King member was allegedly recruited into the Army at a Brooklyn, New York courthouse while awaiting trial for assaulting a New York police officer with a razor."

While gang members make up only a fraction of military personnel, the 2007 NGIC report found that their presence causes an increase in crime, and that "Gang incidents involving active duty personnel on US military bases nationwide include drive-by shootings, drug distribution, weapons violations, domestic disturbances, vandalism, assaults, extortion, and money laundering."

Among the most disconcerting "operations" carried out by gang members in the military involve the theft and trafficking of weapons. In 2006, for instance, "an incarcerated US Army soldier and active gang member identified 60 to 70 gang-affiliated military personnel in his unit allegedly involved in the theft and sale of military equipment and weapons. The solider reported that many of the military personnel in charge of ammunition and grenade distribution are sergeants who are active gang members. The soldier also reported that military commanders were aware of the actions of these gang-affiliated personnel."

That information resembled an interview conducted by authorities one month earlier in which "a former Marine and Gangster Disciple member incarcerated in Colorado detailed how easily soldiers — many of whom were gang members — stole military weapons and equipment and used them on the streets of US cities or sold them to civilian gang members."

Similarly, the NGIC report noted that in August of 2005 "a US soldier in San Antonio was suspected of supplying arms — including hand grenades and bullet-proof vests — to the Texas Mexican Mafia (Mexikanemi), according to uncorroborated but reliable FBI source information."

While uncorroborated, that alleged trafficking is similar to other cases in which trafficking in arms and equipment stolen from the military did occur. In one outrageous case in 2005, an "associate Blood member" was working as a military police officer at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming when he "was charged with theft of body armor stolen from the base." Air Force investigators were able to purchase "vests from gang members following the subject’s arrest for the armed robbery of several gas stations located off base."

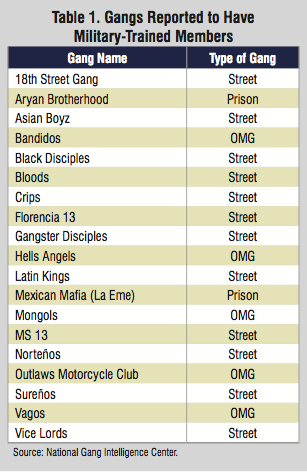

Since then, while gang members are officially banned from duty, the 2009 National Gang Threat Assessment [PDF] produced by the NGIC along with the National Drug Intelligence Center supports the contention that the gang threat in the military has not subsided, or has gotten worse. According to that report:

Members of nearly every major street gang as well as some prison gangs and OMGs [Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs] have been identified on both domestic and international military installations. Deployments have resulted in gang members among service members and/or dependents on or near overseas bases. Additionally, military transfers have resulted in gang members, both service members and dependents/relatives, moving to new areas and establishing a gang presence.

In closing its look at gang members in the military, the NGIC warns, ominously: "While the number of gang members trained by the military is unknown, the threat that they pose … is potentially significant…."