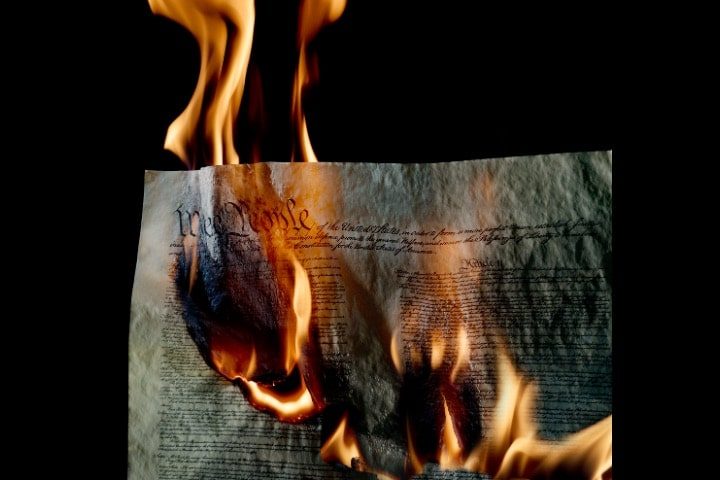

A blog post entitled “Convention of States supporters from the Founders and beyond,” written in 2021 by Gregory Kipp, includes statements made by George Mason, George Washington, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton. The title of the post would lead a reader to believe that the quotations selected from these Founding Fathers proved that they supported the call for another constitutional convention — or convention of states, or amendments convention, or whatever name they call it this week.

Looking over the selected quotations, however, a reader discovers that they simply express those Founding Fathers’ support for a process by which the Constitution could be amended. That’s it. And I am certain that not one of us fighting to avoid the unnecessary risk of a second constitutional convention believes that the Constitution cannot be amended, or that the Founding Fathers didn’t intend for it to be amended. That is not the issue, but reading the quotations on the Convention of States (COS) blog, one would believe that to be the case.

Not one of the statements so prominently included in that blog post could reasonably be construed to express support for the type of convention being flogged and funded by the Convention of States (COS) organization.

To be of service to COS and to anyone who wants to read quotations regarding the type of convention that COS is pouring millions of dollars into promoting, I present the following words of warning spoken and written by many of our Founding Fathers regarding the seriousness of the threat posed by a convention of states to the Constitution and the liberties it was designed to protect. Let’s begin with the man called the Father of the Constitution, James Madison, and then proceed to the man called the Father of His Country, George Washington.

James Madison:

“Conditional amendments or a second general Convention will be fatal.” (Letter to George Nicholas, April 8, 1788)

“The circumstances under which a second Convention composed even of wiser individuals, would meet, must extinguish every hope of an equal spirit of accomodation [sic]; and if it should happen to contain men, who secretly aimed at disunion, (and such I believe would be found from more than one State) the game would be as easy as it would be obvious, to insist on points popular in some parts, but known to be inadmissible in others of the Union.” (Ibid.)

“I am confirmed, by a comparative view of the publications on the subject, and still more of the debates in the several conventions, that a second experiment would be either wholly abortive, or would end in something much more remote from your ideas and those of others who wish a salutary Government, than the plan now before the public.” (Letter to Edmund Randolph, April 10, 1788)

“I should be unwilling to see a door opened for a re-consideration of the whole structure of the government, for a re-consideration of the principles and the substance of the powers given; because I doubt, if such a door was opened, if we should be very likely to stop at that point which would be safe to the government itself….” (Speech in the House of Representatives, June 8, 1789)

George Washington:

“Some respectable characters have wished that the States, after having pointed out whatever alterations and amendments may be judged necessary, would appoint another federal Co[n]vention to modify it upon these documents. For myself I have wondered that sensible men should not see the impracticability of the scheme. The members would go fortified with such Instructions that nothing but discordant ideas could prevail.” (Letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, February 7, 1788)

“It will be more consistent with those circumstances, and far more congenial with the feelings which actuate me, to substitute, in place of a recommendation of particular measures, the tribute that is due to the talents, the rectitude, and the patriotism which adorn the characters selected to devise and adopt them.” (First Inaugural Address, April 30, 1789)

Beyond Madison and Washington, there are other men of the Founding Generation who likewise foresaw the fatal effect an amendments convention could have on the Constitution and on the government created therein.

Melancton Smith, a representative of New York to the Continental Congress wrote:

The amendments contended for as necessary to be made, are of such a nature, as will tend to limit and abridge a number of the powers of the government. And is it probable, that those who enjoy these powers will be so likely to surrender them after they have them in possession, as to consent to have them restricted in the act of granting them? Common sense says—they will not. (“An Address to the People of the State of New York,” April 17, 1788)

Edward Carrington, friend of many Founding Fathers and himself an influential member of that generation, wrote to Thomas Jefferson regarding the risks of a second or amendments convention:

The formers of it [the Constitution] met under powers and dispositions which promised greater accommodation in their deliberations than can be expected to attend any future convention—the particular interests of States are exposed and future deputations, would be clogged with instructions and biassed by the presentiments of their constituents…. (Letter to Thomas Jefferson, October 23, 1787)

Finally, this last selection is lengthy, but I believe it is one of the most timely and to-the-point predictions of what would happen should a new constitutional convention/amendments convention/convention of states be called today. Please read this very closely! And remember: this letter (written anonymously) was published in April 1788! Here, now, I present “A Citizen of New-York: An Address to the People of the State of New York:”

Although the new Convention might have more information, and perhaps equal abilities, yet it does not from thence follow that they would be equally disposed to agree. The contrary of this position is the most probable. You must have observed that the same temper and equanimity which prevailed among the people on the former occasion, no longer exists. We have unhappily become divided into parties, and this important subject has been handled with such indiscreet and offensive acrimony, and with so many little unhandsome artifices and misrepresentations, that pernicious heats and animosities have been kindled, and spread their flames far and wide among us. When therefore it becomes a question who shall be deputed to the new Convention; we cannot flatter ourselves that the talents and integrity of the candidates will determine who shall be elected. Federal electors will vote for federal deputies, and anti-federal electors for anti-federal ones. Nor will either party prefer the most moderate of their adherents, for as the most staunch and active partizans will be the most popular, so the men most willing and able to carry points, to oppose, and divide, and embarrass their opponents will be chosen. A Convention formed at such a season, and of such men, would be but too exact an epitome of the great body that named them. The same party views, the same propensity to opposition, the same distrusts and jealousies, and the same unaccomodating [sic] spirit which prevail without, would be concentred and ferment with still greater violence within. Each deputy would recollect who sent him, and why he was sent; and be too apt to consider himself bound in honor, to contend and act vigorously under the standard of his party, and not hazard their displeasure by preferring compromise to victory. As vice does not sow the seeds of virtue, so neither does passion cultivate the fruits of reason. Suspicions and resentments create no disposition to conciliate, nor do they infuse a desire of making partial and personal objects bend to general union and the common good. The utmost efforts of that excellent disposition were necessary to enable the late Convention to perform their task; and although contrary causes sometimes operate similar effects, yet to expect that discord and animosity should produce the fruits of confidence and agreement, is to expect “grapes from thorns, and figs from thistles.”

I hope this article finds its way into the hands of the Convention of States, but more importantly, I hope it finds its way into the hands of those who might have been tricked by the COS blog post into believing the Founding Fathers would support something I have here shown they so stridently opposed.