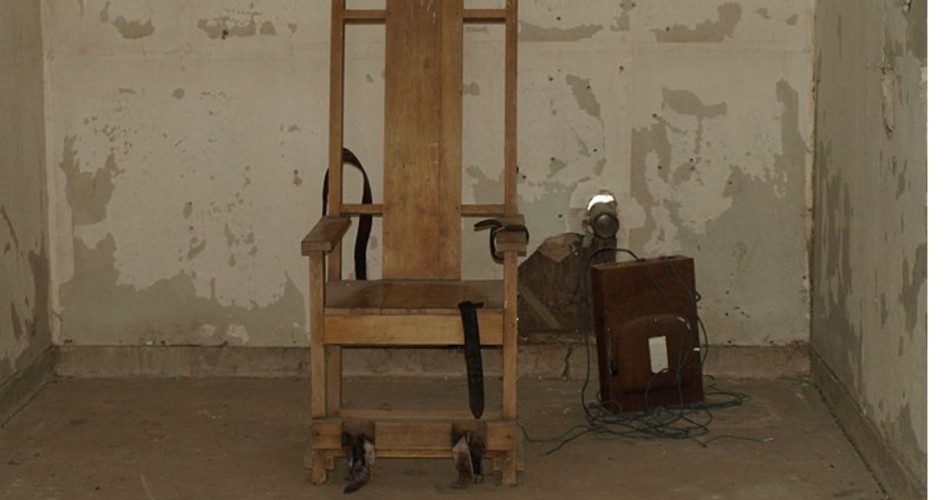

Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam has signed a bill allowing for the use of the electric chair in executions in that state when the appropriate drugs are not available for lethal injection. Botched executions over the past months and an increasing refusal by some foreign manufacturers to make the necessary drugs available has prompted a number of states to look for alternative ways to carry out executions, including a return of such archaic but effective methods as the firing squad.

Haslam’s signature followed passage of the bill in April, with the State Senate voting 23-3 and the House 68-13 to reintroduce the electric chair as an alternative to lethal injection. The bill’s main sponsor, Republican State Senator Ken Yager, explained that he introduced the bill because of “concern that we could find ourselves in a position that if the chemicals were unavailable to us that we would not be able to carry out the sentence.”

Tennessee has 74 inmates on death row, and since 1999, condemned prisoners have had the option of choosing the electric chair over lethal injection. The last one to do so was Daryl Holton, a Gulf War veteran who was electrocuted in 2007 for the murders of his three sons and stepdaughter with a rifle 10 years earlier.

The new law will put the decision in the hands of prison officials, who will decide the means of execution based on the availability of lethal drugs such as pentobarbital, which some European drug makers have refused to sell to state governments for the use of lethal injection, reportedly because of the increasing number of botched executions. In 2009, the U.S. manufacturer of sodium thiopental, another commonly used execution drug, stopped making the drug.

The latest execution gone awry was in April in Oklahoma, where convicted murderer Clayton Lockett, 38, began writhing, clenching his teeth, and lifting his head off the pillow of the death gurney after he was supposed to have been rendered unconscious by the first of three drugs in the state’s death machine. Lockett reportedly finally succumbed to a heart attack 10 minutes after the execution procedure began.

Earlier in the year, convicted murderer and rapist Dennis McGuire gasped and convulsed for some 10 minutes during his lethal-injection execution in Ohio before finally expiring. In 2009, Ohio stopped the lethal injection of convicted murderer Romell Broom after the executioners tried nearly 20 times to get a needle in his veins. Broom remains on death row, but is challenging the state’s right to try to kill him again.

Currently 32 states allow for the death penalty, and while most rely on lethal injection and a handful have the electric chair as a prisoner-preferred option, according to the Washington Post three states also allow the gas chamber (Arizona, Missouri, and Wyoming), three have an option for hanging (Delaware, New Hampshire, and Washington) and two states keep a firing squad on reserve (Oklahoma and Utah).

Richard Dieter of the anti-electric chair Death Penalty Information Center predicted that Tennessee would face legal challenges if it attempts to move ahead with using the device for an execution. “This is unusual and might be both cruel and unusual punishment,” Dieter said in a statement. He charged that making electrocution mandatory in some situations would be “forcing the inmate to use electrocution,” in which case “the inmate would have an automatic Eighth Amendment challenge.” That amendment protects Americans against cruel and unusual punishment.

The day that Haslam signed the electric chair bill, May 20, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a rarely used last-minute stay of execution for a Missouri death-row inmate, Russell Bucklew, telling a lower court to take another look at his case. While the Supreme Court did not offer a reason for its ruling, some observers wonder if the decision of the justices was in some way impacted by the controversy over lethal injection. According to news report, Bucklew suffers from a medical condition that affects his veins.

Meanwhile various groups in Tennessee have come out in force to protest the state’s revised electric chair policy. A United Methodist group opposed to the death penalty in general conducted a prayer vigil May 27 in an attempt to persuade Haslam and the state legislature to stop the new law, slated to go into effect July 1. Nashville’s United Methodist bishop, William T. McAlilly, penned a letter to the governor pointing out that “in only a handful of states is the electric chair still used as a means of capital punishment, because its use constitutes ‘cruel and unusual punishment’ as prohibited by the Constitution of the United States.”

The bishop noted that the “United Methodist Church believes that all human life is sacred and created by God and therefore, we must see all human life as significant and valuable, and that the death penalty denies the power of Christ to redeem, restore, and transform all human beings.”

Proponents of the use of capital punishment as a deterrent to, as well as retribution for, certain heinous crimes note that there is nothing “unusual” about the death penalty in its various present forms. After all, it has been practiced by just men and societies since the beginning of this nation — and throughout history.

As for its cruelty among supposedly Christian peoples, while it is true that Christ came to “redeem, restore, and transform” humanity, executing a person for the killing of another person presents no hindrance to the condemned being redeemed by Christ and restored to God for all eternity if the condemned individual so chooses — even though his body may be killed as punishment for his crime.

One might wonder if Bishop McAlilly and his followers would consider God’s damnation of the unredeemed, for sins and crimes far less repugnant than murder, to constitute “cruel and unusual,” as well as unjust, punishment.

In a 1994 article in The New American, Notre Dame law professor Dr. Charles Rice noted the belief by Church Father St. Thomas Aquinas that the common good requires some individuals to be removed from society through execution. Wrote Aquinas: “The life of certain pestiferous men is an impediment to the common good which is the concord of human society…. Therefore, certain men must be removed by death from the society of men…. Therefore, the ruler of a state executes pestiferous men justly and sinlessly in order that the peace of the state may not be disrupted.”

As for the value of the death penalty as a deterrent, Dr. Rice pointed out that when a “would-be murderer comes at his victim, the victim can rightfully kill him if necessary to save his own life since the murderer by his aggression has forfeited his right to life. Having forfeited his right to live for purposes of immediate self-defense, it is not unreasonable for the murderer to be held to forfeit his life to save the lives of future victims of other would-be murderers.”

Dr. Rice added that the death penalty as a retributive force “involves the rightful use of that penalty to restore [the balance of justice] and thereby to promote the common good. Murder should be stigmatized as the crime of crimes. To punish it by imprisonment — a penalty qualitatively no different from that inflicted for embezzlement — is to devalue innocent life. Seen in this light, the death penalty promotes respect for innocent life.”