There’s little debate among academic economists about the effect of minimum wages. University of California, Irvine economist David Neumark has examined more than 100 major academic studies on the minimum wage. He reports that 85 percent of the studies “find a negative employment effect on low-skilled workers.” A 1976 American Economic Association survey found that 90 percent of its members agreed that increasing the minimum wage raises unemployment among young and unskilled workers. A 1990 survey reported in the American Economic Review (1992) found that 80 percent of economists agreed with the statement that increases in the minimum wage cause unemployment among the youth and low-skilled. If you’re searching for a consensus in a field of study, most of the time you can examine the field’s introductory and intermediate college textbooks. Economics textbooks that mention the minimum wage say that it increases unemployment for the least skilled worker. The only significant debate about the minimum wage is the magnitude of its effect. Some studies argue that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage will cause a 1 percent increase in unemployment, whereas others predict a higher increase.

How about the politics of the minimum wage? In the political arena, one dumps on people who can’t dump back on him. Minimum wages have their greatest unemployment impact on the least skilled worker. After all, who’s going to pay a worker an hourly wage of $10 if that worker is so unfortunate as to have skills that enable him to produce only $5 worth of value per hour? Who are these workers? For the most part, they are low-skilled teens or young adults, most of whom are poorly educated blacks and Latinos. The unemployment statistics in our urban areas confirm this prediction, with teen unemployment rates as high as 50 percent.

The politics of the minimum wage are simple. No congressman or president owes his office to the poorly educated black and Latino youth vote. Moreover, the victims of the minimum wage do not know why they suffer high unemployment, and neither do most of their “benefactors.” Minimum wage beneficiaries are highly organized, and they do have the necessary political clout to get Congress to price their low-skilled competition out of the market so they can demand higher wages. Concerned about the devastating unemployment effects of the minimum wage, Republican politicians have long resisted increases in the minimum wage, but that makes no political sense. The reason is the beneficiaries of preventing increases in the minimum wage don’t vote Republican no matter what; where’s the political quid pro quo?

Higher-skilled and union workers are not the only beneficiaries of higher minimum wages. Among other beneficiaries are manufacturers who produce substitutes for workers. A recent example of this is Wawa’s experiment with customers using touch screens as substitutes for counter clerks. A customer at the convenience store selects his order from a touch screen. He takes a printed slip to the cashier to pay for it while it’s being filled. I imagine that soon the customer’s interaction with the cashier will be eliminated with a swipe of a credit card. Raising the minimum wage and other employment costs speeds up the automation process. I’m old enough to remember attendants at gasoline stations and theater ushers, who are virtually absent today. It’s not because today’s Americans like to smell gasoline fumes and stumble down the aisles in the dark to find their seat. The minimum wage law has eliminated such jobs.

Finally, there’s a nastier side to support for minimum wage laws, documented in my book Race and Economics: How Much Can Be Blamed on Discrimination? During South Africa’s apartheid era, racist labor unions were the country’s major supporters of minimum wage laws for blacks. Their stated intention was to protect white workers from having to compete with lower-wage black workers. Our nation’s first minimum wage law, the Davis-Bacon Act of 1931, had racist motivation. Among the widespread racist sentiment was that of American Federation of Labor President William Green, who complained, “Colored labor is being sought to demoralize wage rates.”

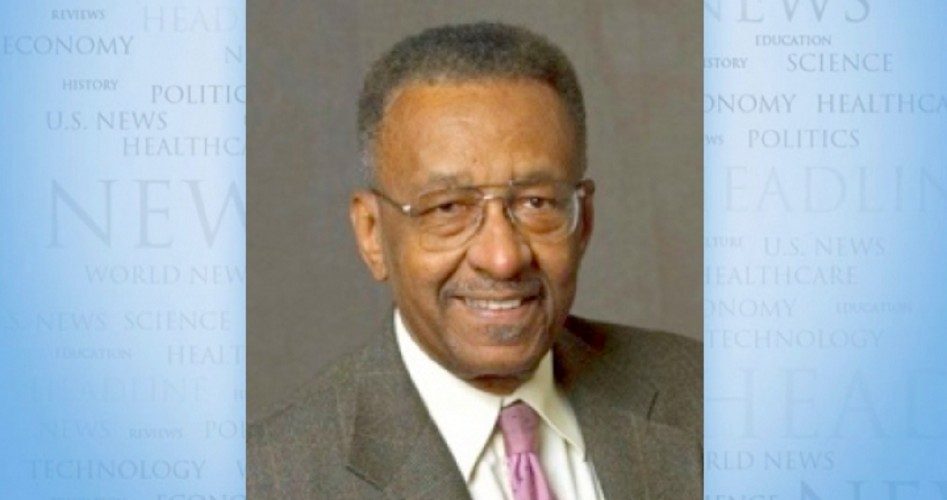

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM