A few years ago, BET had a commentary titled “Where Are the Grocery Stores in Black Neighborhoods?” One wonders whether anyone thinks that the absence of supermarkets in predominantly black neighborhoods means that white merchants do not like dollars coming out of black hands. Racial discrimination cannot explain the absence of supermarkets in black communities.

Compare the operation of a supermarket in a low-crime neighborhood with that of one in a high-crime neighborhood. You will see differences in how they operate. Supermarkets in low-crime neighborhoods often have merchandise on display near entrances. They may have merchandise left unattended outside the store, such as plants and gardening material. Often these items are left out overnight. Supermarket managers’ profit maximizing objective is to maximize merchandise turnover per square foot of leased space. The economic significance of being able to have merchandise located at entrances and outside is the supermarket manager can use all of the space he leases.

Supermarket operation differs in high-crime neighborhoods. Merchandise will not be left unattended outside the store — and surely not overnight. Because of greater theft, the manager will not have products near entrances and exits. As a result, the manager cannot use all of the space that he leases. On top of this, it is not unusual to see a guard employed by the store.

Because supermarkets operate on a very lean profit margin, typically less than 2 percent, crime makes such a business unprofitable. The larger crime cost is borne by black residents, who must pay higher prices, receive inferior-quality goods at small mom and pop stores and/or bear the transportation cost of having to shop at suburban malls. Crime works as a tax on people who can least afford it.

Racial discrimination suits have been brought against pizza companies whose drivers either refuse to deliver pizzas to certain neighborhoods or require customers to come down to their car. In many instances, the pizza deliverymen are black people who are reluctant to deliver pizzas even in their own neighborhoods. For a law-abiding person, not to have deliveries on the same terms as everyone else is insulting, but who is to blame?

It is not just pizzas. Recently, Comcast notified a cable customer on the South Side of Chicago the company would not send out a technician because of the violent crime in the area. Delivery companies do not leave packages in high-crime neighborhoods when the customer is not home. The company must bear the costs of making return trips, or more likely, the customer has to bear the cost of going to pick up the package. Taxi drivers, as well as Uber and Lyft drivers, are reluctant to provide services to high-crime neighborhoods.

Crime and lack of respect for property rights impose another unappreciated cost. They lower the value of everything in the neighborhood. A house that is not even worth $50,000 might be worth many multiples of that after gentrification. Gentrification is a trend in some urban neighborhoods whereby higher-income people buy up property in poor repair and fix it up. This results in the displacement of lower-income families and small businesses. Before we call gentrification an exclusively racial phenomenon, many gentrifiers are black middle-class, educated people.

It is by no means flattering to law-abiding black people that “black” has become synonymous with “crime.” Crime not only imposes high costs on blacks but also sours race relations. Whites are apprehensive of blacks, and blacks are offended by being subjects of that apprehension. That apprehension and offense are exhibited in many insulting ways to law-abiding blacks — for example, jewelers keeping their displays locked and store clerks giving extra surveillance to black shoppers.

White people and police officers cannot fix this or other problems of the black community. If blacks do not fix them, they will not be fixed, at least in a pleasing way.

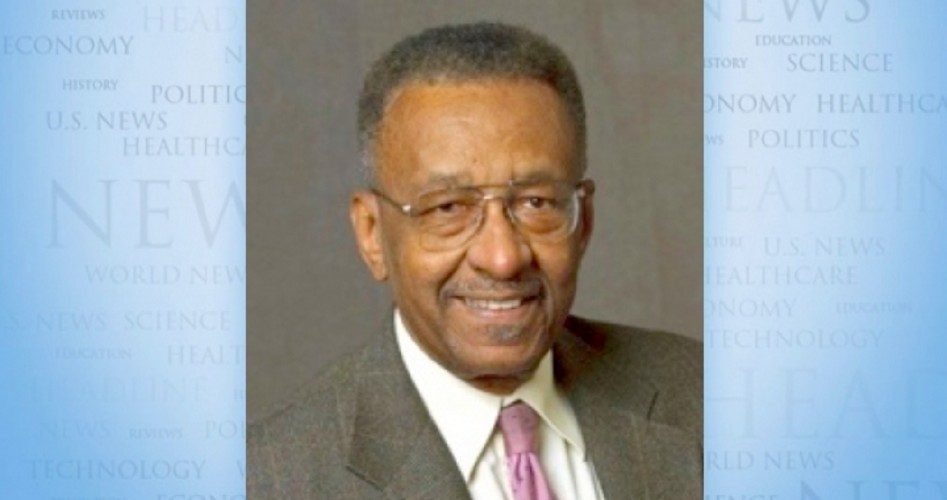

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2016 CREATORS.COM