Washington, Adams, Madison, Jefferson, Franklin. All of these Founding Fathers are well known and need no first names.

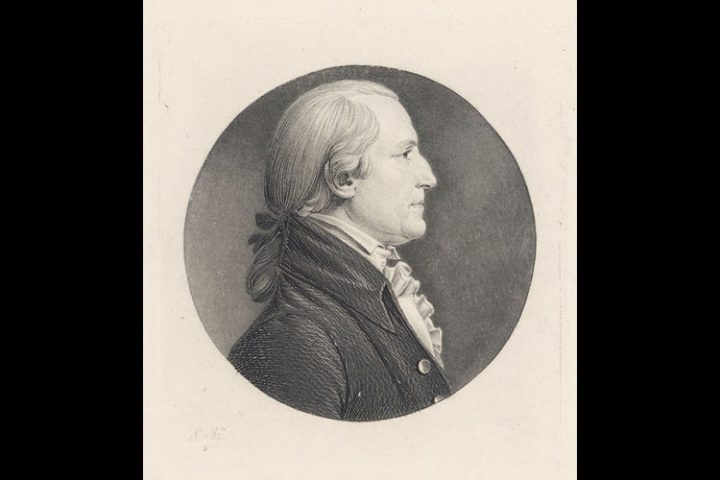

Tucker, however, is a surname of a member of the Founding Generation that for many isn’t familiar, and definitely needs a first name. And what a first name it is: St. George!

St. George Tucker is a man whose name has been scrubbed from the collective memory of Americans, and this is a shame. There was a time when his reputation as an able jurist and a staunch defender of states rights and republican principles was second to none, save only his fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson.

He was a Virginian, but not by birth. Tucker was a transplant from more tropical climes — Bermuda.

Born in July 10, 1752 to a prominent planter family originally from England, Tucker was the youngest of six children who grew up on the estate his family had owned for over 100 years, Grove Plantation.

As a young child, Tucker was curious and studious. His original plan was to study law at one of the prestigious Inns of Law in England, but financial hardship prevented him from following that path.

Undaunted, Tucker was determined to seek his fortune elsewhere, and at 19 years old, he followed a pattern established by many of his extended family members and emigrated to America, hoping to take up the study of law in the colonies.

Arriving in Virginia, St. George was tutored for a time in natural law and philosophy by the Reverend Thomas Gwatkin before matriculating at the Old Dominion’s finest institution of higher learning, the College of William and Mary.

Unfortunately for Tucker, his family was still passing through very tight fiscal straits and he was unable to finish his education at William and Mary. Still determined to receive the training he needed to hang out his shingle and begin the practice of law, in 1772 Tucker sought out noted legal scholar George Wythe.

After two years under Wythe’s tutelage, Tucker was admitted to the bar of Virginia, a colony by now edging ever closer to the brink of hostilities with England.

Just prior to the outbreak of the War for Independence, the courts in Virginia were shut down as armed resistance to British policies began spreading throughout the colony. This left Tucker without a reliable source of employment, so he returned to his native Bermuda to make a living.

Just before sailing home, Tucker told his old classmate Thomas Jefferson that there was an ammunition depot in Bermuda that could be very helpful to the American cause, particularly as ammunition was constantly in short supply in the Continental Army.

Tucker’s father, Henry Tucker, worked with Benjamin Franklin to hammer out an agreement whereby the Americans could bypass the British embargo and purchase the powder and balls kept stored at the Bermuda armory.

Two American ships sailed to Bermuda, took possession of the material, and sailed back to a very grateful George Washington, delivering to the commander-in-chief a much-needed shipment of ammunition. Later in life, Tucker would relate that he himself helped carry the casks full of power onto the American vessels.

Naturally sympathetic to the American cause of liberty, Tucker started working in his family’s trade enterprise, serving as a liaison between his father and representatives of the American war effort. His first and most lucrative contracts called for violating the British ban on trading with her rebellious colonies, by hauling rifles, ammunition, and salt, invaluable commodities to an army on the verge of collapse and conquer.

Not satisfied with simply supplying the American patriots with weapons, Tucker joined the Virginia militia, serving as a major under Nathanael Greene at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Tucker received wounds during this historic battle and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. After his wounds had healed sufficiently, Tucker returned to his unit just in time to participate in the siege of Yorktown in 1781. Here, too, Tucker was injured and his military career came to an early end.

Though war wounds may have closed the door on his military career, his extraordinary talent for writing opened a window through which would flow some of the most influential and insightful works of his generation.

Undoubtedly the most influential and well-known of Tucker’s post-war writings was his View of the Constitution, published in 1803 while he worked as a professor at William and Mary.

Its current publisher, Liberty Fund, describes View of the Constitution as “the first extended, systematic commentary on the United States Constitution after its ratification and later its amendment by the Bill of Rights.”

The essay began merely as a small section of Tucker’s magnum opus, a “republicanized” edition of the unparalleled legal treatise, Commentaries on the Laws of England by William Blackstone. A thorough study of Blackstone was undoubtedly the sine qua non of legal education in America, but after Tucker’s version was published, “generations of American law students, lawyers, judges, and statesmen learned their Blackstone — and also their understanding of the Constitution — through Tucker,” the Liberty Fund introduction to their edition explains.

Noted constitutional scholar and states rights advocate Professor Clyde Wilson describes the impact of Tucker’s scholarship on American political philosophy, saying, “Though nearly forgotten since, Tucker’s work remains an important piece of constitutional history and a key document of Jeffersonian republicanism.”

On this July 10, the 271st anniversary of his birth, we seek to reintroduce 21st-century patriots with the power that comes from the pen of a forgotten Founder and advocate of limited government and the states’ obligation to reject and refuse to enforce any act of the federal government that exceeds the constitutional boundaries of its power. The manner best suited to celebrate Tucker is to present this brief summary of some highlights of his View of the Constitution.

First, a simple primer on the text. Tucker divides the essay into two parts: first, a recitation of the formation of the Constitution and the nature of the confederacy it created; second, a description of the intended allocation of authority between the states and the federal government. In this era of unchecked growth of the federal government and constant capitulation of states that are little more than administrative subunits of the Leviathan, few topics could be more timely.

As for how the Constitution was created, Tucker comes down firmly on the side of the so-called compact theory, explaining:

The constitution of the United States of America, then, is an original, written, federal, and social compact, freely, voluntarily, and solemnly entered into by the several states of North-America, and ratified by the people thereof, respectively; whereby the several states, and the people thereof, respectively, have bound themselves to each other, and to the federal government of the United States; and by which the federal government is bound to the several states, and to every citizen of the United States.

Then, lest there be any confusion as to what was meant by the words “compact” or “federal,” Tucker helpfully defines these key constitutional concepts.

A compact, Tucker explains, is a type of agreement in which

the contracting parties, whether considered as states, in their politic capacity and character; or as individuals, are all equal; nor is there any thing granted from one to another: but each stipulates to part with, and to receive the same thing, precisely, without any distinction or difference in favor of any of the parties.

Next, Tucker puts a finer point on the issue, echoing James Madison’s Federalist 39, averring that the Constitution is

[A] federal compact; several sovereign and independent states may unite themselves together by a perpetual confederacy, without each ceasing to be a perfect state.

Regarding the retention of authority by the states that formed the federal government, Tucker reveals the real, proper relationship between states and the central government:

The state governments not only retain every power, jurisdiction, and right not delegated to the United States, by the constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, but they are constituent and necessary parts of the federal government; and without their agency in their politic character, there could be neither a senate, nor president of the United States; the choice of the latter depending mediately, and of the former, immediately, upon the legislatures of the several states in the union.

[T]he general powers are limited, and that the states, in all unenumerated cases, are left in the enjoyment of their sovereign and independent jurisdictions.

Then, as if that weren’t quite clear enough (and our contemporary climate of federal overreach proves that it wasn’t), Tucker puts a final touch on the topic, restating the purpose of the 10th Amendment:

The powers delegated to the federal government being all positive, and enumerated, according to the ordinary rules of construction, whatever is not enumerated is retained.

Finally, Tucker didn’t view the Constitution through rose-colored glasses. In fact, he recognized that

All governments have a natural tendency towards an increase, and assumption of power, and the administration of the federal government has too frequently demonstrated that the people of America are not exempt from this vice in their constitution.

We have seen that parchment chains are not sufficient to correct this unhappy propensity; they are, nevertheless, capable of producing the most salutary effects; for, when broken, they warn the people to change those perfidious agents, who dare to violate them.

What, then, could keep the people powerful enough to throw off a tyrant who has repeatedly encroached upon the liberty of the people? Tucker had an answer for that one, too, that could not be more contemporarily relevant.

Finally, Tucker explains in one paragraph the purpose of the Second Amendment, as well as a warning to future Americans who might see the rights protected by it being revoked by tyrants:

This may be considered as the true palladium of liberty.… The right of self defense is the first law of nature: in most governments it has been the study of rulers to confine this right within the narrowest limits possible. Wherever standing armies are kept up, and the right of the people to keep and bear arms is, under any color or pretext whatsoever, prohibited, liberty, if not already annihilated, is on the brink of destruction.

In light of his fearless and historically sound support of the power of states to disregard any act of the federal government that is not clearly granted by the states in the Constitution, it isn’t hard to see why the establishment has scrubbed the name, legacy, and constitutional interpretation from our cultural memory, as well as from the history of the post-Revolutionary era.

St. George Tucker’s exemplary and illuminating scholarship should not be hidden under a bushel. Americans must once again become familiar with a prolific and persuasive member of the Founding Generation whose View on the Constitution should be read, recited, and remembered by all who strive to restore the liberties granted to us by God and protected by the Constitution.