Black politicians, civil rights organizations and others who say they are concerned with the welfare of poor black people often support harmful measures. One of the most effective tools for disadvantaged people is to be able to charge a lower price for what they sell and pay a higher price for what they buy. Let’s look at this principle first using a couple of nonracial examples.

How does chuck steak compete with a more preferred cut such as filet mignon? Everyone knows the answer. It sells for a lower price, say $7 a pound compared to filet mignon’s $20. Suppose one wanted to rig the market against chuck steak. He need only lobby the legislature to set a minimum price for steak, say $15 a pound.

Many customers would voluntarily discriminate against chuck steak in favor of the more preferred filet mignon. The reason is simple. Before the law, it cost 13 additional dollars per pound to discriminate in favor of filet mignon. With a minimum steak price of $15 a pound, it only costs five additional dollars to do so. A fundamental law of economics posits that the lower the cost to do something the more people will do of it. That applies to doing anything, including discrimination.

What about the opposite of setting not minimum prices but maximum prices like a price ceiling? Again, let’s begin by using a nonracial example. Suppose you see a fat, old, ugly cigar-smoking man married to a beautiful young woman. What would you predict about the man’s income? I’m guessing you’d predict it was high. The fat, old, ugly cigar-smoking man essentially propositions: I can’t compete for your hand on the basis of a guy like Williams, so I’m going to offset my disadvantages by offering you a high price. Some might conclude that it’s unfair for pretty women to exact higher terms from fat, old ugly men than from handsome men. If they managed to enact a law banning such a practice, they would take away the less preferred man’s most effective means of competing with the more preferred man: offering a higher price.

How about a couple of real-world examples of minimum prices? During South Africa’s apartheid era, the secretary of its avowedly racist Building Workers’ Union said, “There is no job reservation left in the building industry, and in the circumstances, I support the rate for the job (minimum wage) as the second-best way of protecting our white artisans.” The South African Nursing Council condemned low wages received by black nurses as unfair. Some white nurses said they would refuse wage increases until the wages of black nurses were raised.

Racist intentions were obvious during the legislative debate on the Davis-Bacon Act (1931), the nation’s first federal minimum wage law. Among the statements of support for this racially discriminatory law were those of Rep. William Upshaw, D-Ga., who complained about the “superabundance or large aggregation of Negro labor.” Rep. Miles Allgood, D-Ala., said, “That contractor has cheap colored labor that he transports, and he puts them in cabins, and it is labor of that sort that is in competition with white labor throughout the country.” American Federation of Labor President William Green complained, “Colored labor is being sought to demoralize wage rates.”

How about the right to pay higher prices? During grossly racially discriminatory times, one could not prevent whole urban neighborhoods from going from white to black virtually overnight. Blacks simply outbid whites. For example, a white family might have rented a three-story brownstone for $100 a month. Maybe six black families told the landlord that if he’d cut the building into six parts, they’d pay him $50 a month for each unit. Landlords found the higher income preferable to their discriminatory preferences. If there were a law setting a $100 maximum rent on a three-story brownstone, discriminated-against poor people could not compete with wealthier more preferred people.

Minimum and maximum prices are but two ways do-gooders handicap poor and discriminated-against people.

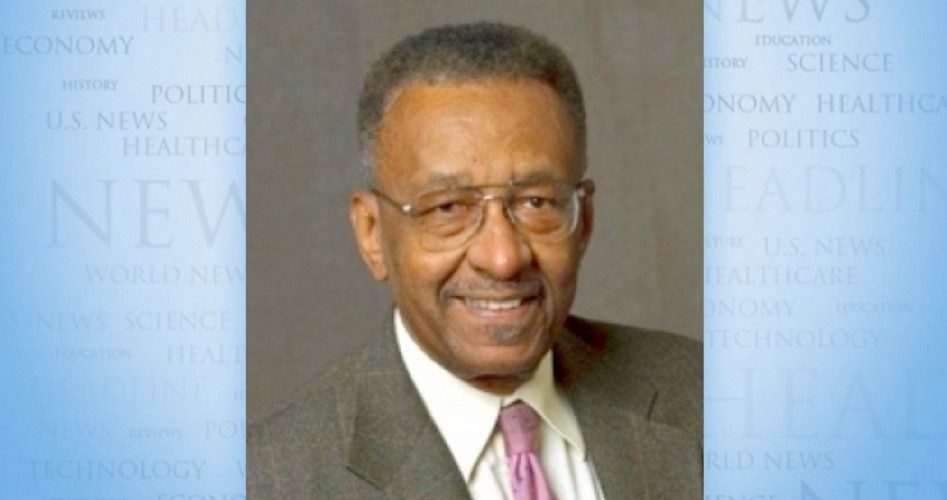

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM