Now that statues of Presidents Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, Grant and Theodore Roosevelt have been desecrated, vandalized, toppled and smashed, it appears Woodrow Wilson’s time has come.

The cultural revolution has come to the Ivy League.

Though Wilson attended Princeton as an undergraduate, taught there and served from 1902 to 1910 as president, his name is to be removed from Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs.

And why is this icon of American liberals to be so dishonored?

Because Thomas Woodrow Wilson disbelieved in racial equality.

Says Princeton President Christopher Eisgruber: “Wilson’s racist opinions and policies make him an inappropriate namesake.” Moreover, Wilson’s “racism was significant and consequential even by the standards of his own time.”

And what exactly were Wilson’s sins?

“Wilson was … a racist,” writes Eisgruber, who “discouraged black applicants from applying to Princeton. While president of the United States he segregated the previously integrated civil service.”

Another of Wilson’s crimes was overlooked by Eisgruber.

In February 1915, following a White House screening of “Birth of a Nation,” which depicted the Ku Klux Klan as heroic defenders of white womanhood in the South after the Civil War, a stunned Wilson said:

“It’s like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

Princeton’s board of trustees has endorsed Eisgruber’s capitulation, declaring that Woodrow Wilson’s “racist thinking and policies make him an inappropriate namesake for a school or college whose scholars, students, and alumni must stand firmly against racism in all its forms.”

Yet, as Wilson left the U.S. presidency a century ago and has been dead for 96 years, one wonders: Was Princeton unaware that Wilson had resegregated the civil service? When did Princeton discover this?

Wilson’s support of segregation was a matter of record in his own time and is a subject about which every biographer and historian of that period has been aware. When did Princeton discover that this Southern-born president, the most famous son in the school’s history, like so many of his presidential predecessors, did not believe in integration?

Four years ago, Eisgruber rebuffed student demands to wipe Wilson’s name off the public policy institute, because, as he wrote last week, Wilson “transformed” Princeton “from a sleepy college to a world-class university.”

Talk of ingratitude! Woodrow Wilson is being dishonored today by the house that Woodrow Wilson built.

Wilson was also a history-making liberal Democrat, a two-term president who took us into the Great War, advanced his “14 Points” as a basis for peace, became an architect of the Versailles Treaty, championed a League of Nations and won the Nobel Prize for Peace.

True, it did not all work out well.

Sold as “the war to end war” and “to make the world safe for democracy” Wilson took us in in April 1917 as an associate power of four empires. And rather than make the world safe for democracy, the war made the world that emerged accessible to Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini and Hitler.

Yet, if Wilson’s disbelief in equality is sufficient to get the most famous son Princeton produced from having his name on a public institute, this is likely just the beginning.

The Wilson Center, chartered by Congress in 1968, a nonpartisan policy forum led today by ex-Congresswoman Jane Harman, is the official memorial to President Wilson in Washington, D.C.

It, too, is likely to be headed for the chopping block.

One of the largest and most integrated public high schools in D.C. is Woodrow Wilson High, which has stood since before World War II in the northwest corner of the city. Is that name to be changed as well?

What of the D.C. Beltway’s Wilson Bridge, south of the city, which has brought traffic into, out of and around the capital for decades?

Will we need a name change there as well?

Theodore Roosevelt is under fire for his negative views of Native Americans. Yet, he, too, has a bridge over the Potomac named after him — and a D.C. high school as well.

The Key Bridge connects Georgetown to Virginia’s Lee Highway, which was named for General Robert E. Lee in 1919. The bridge is named after Francis Scott Key, author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and whose statue was lately toppled in Golden Gate Park.

If support for segregation is a disqualification for honor in the new America, is it likely that the oldest of three Senate office buildings on Capitol Hill can remain named for Sen. Richard B. Russell of Georgia?

A confidant and ally of President Lyndon Johnson, Russell was a co-signer of the Southern Manifesto of 1956, which called for “massive resistance” to integrating public schools. Russell also voted against every major civil rights bill in his 40 years in the Senate.

If D.C. ever becomes a state surrounding the Capitol, Mall, White House and major monuments, look for the sweeping destruction of statues and monuments and a changing of the names of streets, parks and circles.

Where does the madness end?

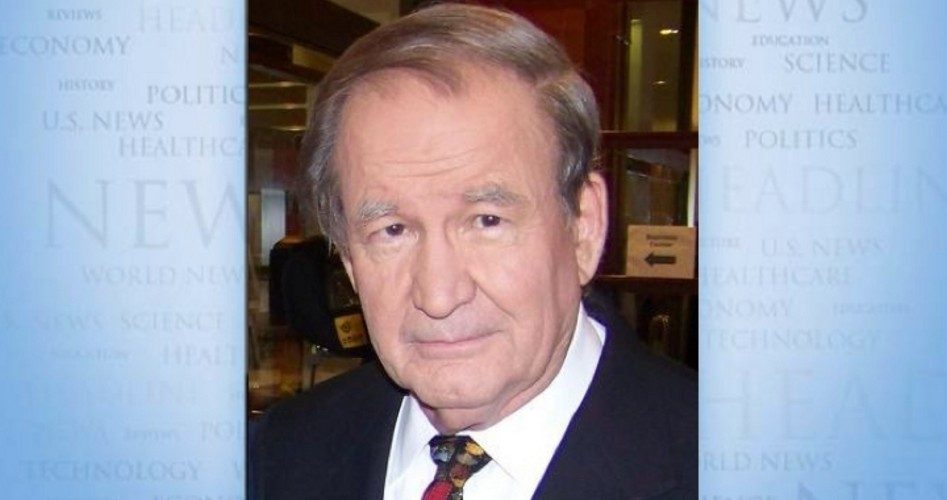

Photo of Patrick J. Buchanan: Bbsrock — Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Patrick J. Buchanan is the author of Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever. To find out more about Patrick Buchanan and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators website at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2020 CREATORS.COM