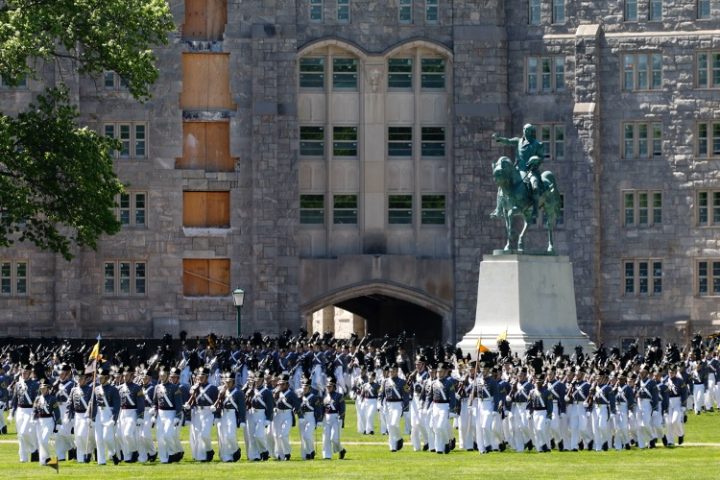

Mottos and slogans do sometimes change, for better or worse. Google retired “Don’t be evil” in 2015; some may say rightly so, too, that its standard now is “Don’t be evil — leave that to us.” Reebok had a slogan “Cheat on your girlfriend, not on your workout” that ran only briefly in Germany, for obvious reasons. Nivea had a “White is Purity” slogan that hit the market in 2017 in the Mideast, but was quickly nixed because, as any wokester knows, “white is privilege.” And now media claim that the vaunted military academy West Point has joined the club.

That is, its mission statement “Duty, Honor, Country” has been “exchanged,” media point out, for “Army values.” What are army values?

(Well, it would depend on what army you’re talking about. See Attila the Hun, Genghis Khan et al.)

In fairness, though, after doing a little digging, I learned that West Point does specify. And on the U.S. Army’s “The Army Values” page is listed “Duty” and “Honor,” along with “Loyalty,” “Respect,” “Selfless Service,” “Integrity,” and “Personal Courage.” I’m not sure how “Personal Courage” differs from “Courage” (is there such thing as “impersonal courage”?), which is technically a virtue. The charitable interpretation is that “Personal” is here an intensifier; the more critical one is that it’s another irritating redundancy, a painfully common example of which is “lived experience.” (I’ve yet to meet anyone who has benefited from “un-lived” experience. But, then again, I’m a kid compared to a large sequoia tree.)

This said, The Army Values page does seem pretty wholesome, with a valid explanation for each “value.” Additionally, “In the past century, West Point’s mission has changed nine times,” explained West Point superintendent Lieutenant General Steve Gilland in a mission statement update. “Many graduates will recall the mission statement they learned as new cadets did not include the [following] motto, as Duty, Honor, Country was first added to the mission statement in 1998.”

“Duty, Honor, Country is foundational to the United States Military Academy’s culture and will always remain our motto,” Gilland also pointed out.

In other words, it’s understandable that in this “woke” time, in which the walls of civilization are crumbling under the weight of moral and cultural corruption, critics are trigger happy vis-à-vis perceived politically correct trespasses. Viewing West Point with a jaundiced eye is fair, too, given past incidents such as the alleged coddling of a vocally communist cadet named Spenser Rapone. (Update: After the Army came under pressure, Rapone was, reportedly, “administratively discharged.” In 2021 it was learned that, surprise, surprise, he was a Ph.D. candidate and teaching assistant at the University of Texas-Austin. Academia never disappoints!) Nonetheless, insofar as the motto story goes, it doesn’t appear there’s any “there” there.

Yet this doesn’t mean this can’t be a teaching moment. In particular, of interest is West Point’s, and most everyone else’s, touting of “values.” Commentator George F. Will treated this terminological matter well in 2000, writing:

Today it would be progress if everyone would stop talking about values. Instead, let us talk, as the Founders did, about virtues.

Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb rightly says that the ubiquity of talk about “values” causes us to forget how new such talk is. It began in Britain’s 1983 election campaign, when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher jauntily embraced the accusation, which is what it was, that she favored “Victorian values.”

Time was, “value” was used mostly as a verb, meaning to esteem. It also was a singular noun, as in “the value of the currency.” In today’s politics, it is primarily a plural noun, denoting beliefs or attitudes. And Friedrich Nietzsche’s nihilistic intention — the de-moralization of society — is advanced when the word “values” supplants “virtues” in political and ethical discourse. When we move beyond talk about good and evil, when the language of virtue and vice is “transcended,” we are left with the thin gruel of values-talk.

How very democratic values-talk is: Unlike virtues, everyone has lots of values, as many as they choose. Hitler had scads of values. George Washington had virtues. Who among those who knew him would have spoken of Washington’s “values”?

To be precise, “values’” origin (in the sense of “principles, standards”) only dates back to, quite tellingly, 1918 and the progressive era. It’s part of what G.K. Chesterton called the “atheistic literary style.”

Unlike virtues, “values” are not good by definition; they’re just “ideas people value” by definition. A saint treasuring holiness and a sociopath treasuring hatefulness both have values — but only one exhibits virtue.

“Virtue” is out of favor because it is that set of “objectively good moral habits,” and in an age in which that objective thing called “morality” is called an illusion because it’s fancied mere “social construct,” “good” is reckoned a relative term. Of course, everything transcendent is thought relative in a philosophically materialistic time (“good’s” existence is dependent on God’s, as I explain here).

To further illustrate the distinction here, we might call someone virtuous but not “valuous,” not any more than we’d label a chair or anything else that occupies space and has mass matterous; there’s nothing notable about embodying something everyone/thing has.

So Will was right: We should talk about virtues, not values. But this won’t happen unless we again start talking about God, not just man. And God, mind you, is what’s really missing from The Army Values. And such remissness, unless remedied, will guarantee ultimate defeat.