What is the purpose of studying history? Why do we care what happened more than 2,200 years ago? In his History of Rome, Livy suggests one reason:

The study of history is the best medicine for a sick mind; for in history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see; and in that record you can find for yourself and your country both examples and warnings; fine things to take as models, base things, rotten through and through, to avoid.

In other words, we study history that we might be able to learn from the mistakes of our ancestors and not repeat them, and to learn of their successes and try to model them. Simple as that. We read the records of history and we liken the stories to our own time with the intent that we might profit from that investment of time. And so it is with the story I’m relating to you today: the story of the Second Punic War.

The very name “Second Punic War” reveals that there was a First Punic War. The First Punic War ended about 20 years before the second one began and featured the same belligerents: Rome and Carthage.

You might ask yourself why a war between Rome and Carthage would be called “Punic.” Punicus was the ancient name of Carthage, reflecting the reputed settling of that area of North Africa by the Phoenicians. So, Punic means “about Punicus,” thus Punic Wars means “wars with Punicus,” or Carthage.

First Punic War

Rome’s power and influence was increasing around the Mediterranean, and Carthage didn’t fancy the competition. A brilliant Carthaginian general named Hamilcar Barca decided to take a shot at conquering Rome, a jumped up village that he reckoned was boxing above its weight class.

To Hamilcar’s regret and to the regret of all the citizens of Carthage, he underestimated Rome’s resolve, as well as her military might, and that mistake cost Carthage mightily. As punishment for Hamilcar’s hubris, Rome imposed very harsh terms of surrender on Carthage. Most importantly, Carthage had to cede control of its Mediterranean islands to Rome. That pretty much scuppered any chance Carthage would ever have to expand its empire eastward.

Defeated, but not dissuaded, Hamilcar looked west as a way to expand, but in a direction away from Rome. His focus was on Spain.

Hamilcar figured he could expand Carthage through the Iberian peninsula and Gaul (modern day France), conquering territory, taking spoils, conscripting soldiers, and hiring mercenaries until Carthage could be a contender again, one strong enough to exact revenge on Rome.

In preparation for setting off to try to conquer Spain, Hamilcar called one of his sons to accompany him to the altar as he sacrificed a bull to the gods, imploring them to grant him success in Spain.

The nine-year-old boy went with his father to the temple, put his little hands on the blood-soaked altar and, as Polybius tells it, said, “I swear that as soon as I am old enough I am going to be Rome’s deadliest enemy!” He then stomped his foot in the dust, promising he would not stop punishing Rome until either Carthage or Rome was reduced to dust just like the dust that blew up around his foot.

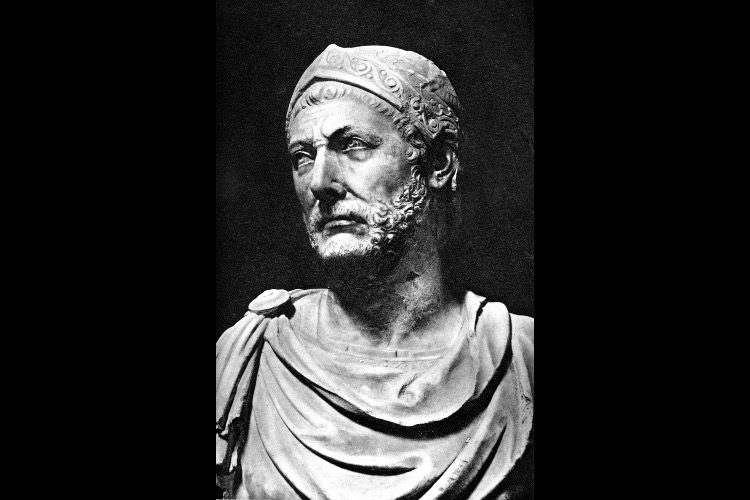

This boy with the bellicose bravado is the famous Hannibal, a general who grew to such great fame that he eclipsed the reputation and renown of his father. He was born about 247 B.C. and his parents wanted his name to remind him of who should be and what great things he should try to accomplish.

Hannibal means “Baal, be merciful to me.” Baal was the Carthaginians’ God of Fertility who manifested himself in thunderstorms. And he was the God to whom Hannibal would make sacrifices for the rest of his life. His surname, Barca, meant “thunderbolt,” so, Hannibal’s name literally meant “divine thunder and lightning.” And Rome definitely experienced the destructive deluge of the mighty storm that was Hannibal.

Hamilcar, Hannibal, Hamilcar’s son-in-law Hasdrubal, and the Carthaginian army landed in Spain in 236 B.C. and established a colony they named New Carthage. The remains of this city can be seen today in Cartagena, Spain. Curious how across more than two millennia it’s still called “Carthage.”

Polybius tells us that the native tribes were brought under Carthage’s power either by “diplomacy or force of arms.”

Nine years later, Hamilcar died in battle. After being ruled for seven years by Hasdrubal, command of the armies of Carthage finally fell to 26-year-old Hannibal, who eagerly and with revenge on his mind set his sights on Rome.

Hannibal remembered his oath and decided to leave Spain and begin his plan to invade, conquer, and rule Rome. Hannibal decided to go around the coast of Spain, cross the Alps and conquer all of Italy from the north to the south.

A quick look at a map will reveal why crossing the Alps wasn’t the typical road to Rome.

As Hannibal made his way through southern Spain, he approached a town called Saguntum, a town which also still exists today and retains its old name: Sagunto, Spain. The Roman senate heard of this and sent a special representative to meet with Hannibal to warn him that any aggression against Saguntum would be considered an act of war.

Second Punic War

Hannibal ignored the Roman representative — as well as the orders of the Senate of Carthage — not to attack Saguntum, and he destroyed Saguntum. While this is considered the beginning of the Second Punic War, Polybius blames Hannibal’s ambition and lust for power.

Hannibal, despite his father’s disastrous underestimating of Rome, reckoned Rome was being too pushy in its effort to exert its power in Spain, and Rome thought Hannibal represented Carthage — he didn’t; he was disobeying his government’s orders — was being pretty bold for a country that got humiliated in war only 20 years or so ago. War was on!

Ultimately, the senate of Carthage was compelled to grant Hannibal power to fight Rome, and that made Hannibal very happy. He headed out across the Alps with an army that eventually included more than 100,000 foot soldiers, 20,000 cavalry, and, most famously, 37 African elephants.

In response, Rome sends one of the consuls — Publius Cornelius Scipio — to head off Hannibal before he, the army, and the elephants could cross the Rhone River. Scipio arrived three days too late, and Hannibal was already approaching the foothills of the Alps and Italy.

The Alps were more of a problem for Hannibal’s Army than Scipio was, though. Livy writes this about the reaction of Hannibal’s African-born troops to the sight of the snowy mountains:

But the sight of the Alps revived the terrors in the minds of his men. Although rumor, which generally magnifies untried dangers, had filled them with gloomy forebodings, the nearer view proved much more fearful. The height of the mountains now so close, the snow which was almost lost in the sky, the wretched huts perched on the rocks, the flocks and herds shriveled and stunted with the cold, the men wild and unkempt, everything animate and inanimate stiff with frost, together with other sights dreadful beyond description — all helped to increase their alarm.

It wasn’t as if there was no reason to worry. As Hannibal and the animals and men climbed higher, the snow became deeper, the ledges became narrower, and hundreds of men and animals slid to their death.

Livy tells us that Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps took 15 days. Hannibal reports he lost 36,000 men and most of his elephants. He came out of the mountains and onto the plains by the Po River.

Scipio was waiting for Hannibal, counting on the young commander and his forces to be near to death from traversing the Alps.

But so far from dead were Hannibal and his men that the Roman Senate recalled all the armies from throughout the lands controlled by Rome to come home and defend the homeland.

Weak and weary as they might have been, Hannibal and the Carthaginians defeated Scipio and the Roman legions gathered there. Scipio hurried back to Rome to recruit reinforcements.

Hannibal chased Scipio, and about a month later, he beat the combined armies of both the consuls, and the citizens of Rome were terrified. Livy writes that Romans worried that any day Hannibal would burst through the city gates and take them all to Carthage to be slaves.

In fact, for centuries after the Second Punic War, Roman parents would tell their children who refused to go to bed on time that “Hannibal was at the gates,” and that if they didn’t go to bed, he would kidnap them.

By 217 B.C. Hannibal was laying waste to the towns and villages of Italy and hastening toward the grand prix: Rome.

By this time, there were two new consuls, and one of them — Gaius Flaminus — met Hannibal at Lake Trasimene and by the end of the engagement, Hannibal and his men had killed 15,000 Roman soldiers, while the Roman legions had taken the lives of only 2,500 Carthaginian troops.

When the news of this latest thrashing reached Rome, the people were beyond consolation. Livy writes, “As soon as the news of this disaster reached Rome the people flocked into the Forum in a great state of panic and confusion.”

With Hannibal marching ever closer to the gates of Rome, the Senate, sensing that the city was facing a clear and present danger, appointed a dictator, a constitutional protection for the peace of Rome when destruction seemed imminent.

Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, surnamed Cunctator (“the delayer”), was the man chosen to serve the constitutionally mandated term of six months. As dictator, Fabius was the commander of the armies of Rome, and he decided to pursue a strategy of avoiding open battles, choosing rather to use guerrilla strikes and delay to gradually wear down Hannibal by exhausting his supplies.

This delaying tactic is known in military history as a Fabian tactic, in honor of the dictator Quintus Fabius Maximus.

It’s worthwhile to note that George Washington was called the “American Fabius” for his success in using Fabian-style delay tactics against the British forces.

A year later, the two new consuls thought they’d try again to stop Hannibal and save Rome, after trying unsuccessfully for a year to wear him down. The two consuls led the Roman army for a final fight against Hannibal in the peninsula. That encounter is known as the Battle of Cannae.

The slaughter at Cannae seemed decisive. The losses to the legions were incalculable, and the people of Rome had no stomach for sacrificing more of their sons and husbands to Hannibal.

While he stood there on the very threshold of fulfilling his father’s fondest wish and his own sacred oath, Hannibal seemed to suffer from what would today be called “imposter syndrome.” Here’s Livy’s description of the scene in the camp of Carthage after their total obliteration of the Roman army at Cannae:

Hannibal’s officers all surrounded him and congratulated him on his victory, and urged that after such a magnificent success he should allow himself and his exhausted men to rest for the remainder of the day and the following night. Maharbal, however, the commandant of the cavalry, thought that they ought not to lose a moment. “That you may know,” he said to Hannibal, “what has been gained by this battle I prophesy that in five days you will be feasting as victor in the Capitol. Follow me; I will go in advance with the cavalry; they will know that you are come before they know that you are coming.” To Hannibal the victory seemed too great and too joyous for him to realise all at once. He told Maharbal that he commended his zeal, but he needed time to think out his plans. Maharbal replied: “The gods have not given all their gifts to one man. You know how to win victory, Hannibal, you do not how to use it.” That day’s delay is believed to have saved the City and the empire.

Hannibal’s delay did, indeed, ultimately, save Rome. To this day, historians debate the cause of Hannibal’s historically significant hesitation.

The prevalent theory is that, although their campaign was a catalog of one success after another, Hannibal’s men began to feel the strain of nearly 15 years at war, and were anxious to get home.

They weren’t the only ones anxious to get to Spain and Carthage: So was Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.

Fall of Carthage

Scipio was elected consul in 205 B.C. and he convinced the Senate and the people that he could end the war, not by defeating Hannibal in Italy, but by invading an all but undefended Carthage.

The Senate of Carthage called Hannibal and his army back to Carthage to defend the city from Scipio and the Roman legions.

Ultimately, the two great generals — Scipio and Hannibal — faced off at the Battle of Zama.

Before the combat began, though, Hannibal and Scipio tried to negotiate a settlement, to no effect. As Livy reports, “Thus, no understanding was arrived at and the commanders rejoined their armies. They reported that the discussion had been fruitless, that the matter must be decided by arms, and the result left to the gods.”

Scipio and the armies of Rome then set about obliterating Carthage — absolutely razing it. It is no exaggeration to say that the Romans mercilessly humiliated the people and the Senate of Carthage.

It all comes down to the fact that Carthage was defeated and Rome punished her severely, making it impossible for the people of Carthage to ever recover their liberty, and they were to remain forever subjects to Rome.

For us, the takeaway is obvious: The government of Carthage could have prevented this. The people of Carthage could have prevented this. To us it remains to profit from the denigration, demise, and debasement of once mighty Carthage.

There was a phrase famous among the Romans and among our Founding Fathers when speaking of opposing tyranny: principiis obsta. It means “stop it at the beginning.” Now, obviously we cannot stop the tyranny at its beginning, but we can stop it at the beginning of our learning of it!

Now we come to Hannibal’s final appearance on the world’s stage as a leading man. He sat in the Senate of Carthage while that body discussed the harsh penalties imposed by Rome for Hannibal’s having instigated a war against Rome.

Hannibal’s final message is powerful, timeless, and, sadly, timely. Read his words carefully so that they might be a warning to us, lest someday we find ourselves wishing we had heeded them, wishing we’d fought back, but, like the Carthaginians, without weapons, without property, and without liberty.

Here is Livy’s description of the scene in the Senate of Carthage, the day that Hannibal spoke his last words before that body. After delivering this powerful rebuke, Hannibal abandoned his home and wandered.

Exhausted by a long war with Rome and with the harsh terms of the peace imposed upon them, senators of Carthage sat weeping with regret. On this occasion, Hannibal sat laughing. A senator rebuked Hannibal for laughing while the people mourned their great loss of liberty and property. Hannibal replied:

If you could discern my inmost thoughts as plainly as you can tell the expression of my countenance you would easily discover that this laughter which you find fault with does not proceed from a merry heart but from one almost demented with misery. All the same, it is very far from being so ill-timed as those foolish and misplaced tears of yours. The time to cry was when our weapons were taken from us, when our ability to travel and defend ourselves was denied us. A very powerful people, apparently safe from all foreign foes, have fallen victim to their overestimation of their own strength. How true it is that we only feel loss of liberty when it affects our private interests and how it always takes a loss of money to feel that effect. So, when others were being stripped of their property and their weapons, none of you complained, but now, when it’s your property and your weapons you behave like mourners at your country’s funeral. All too soon I fear you will realize that our liberty died long ago, with no one there to mourn her.

Let us learn from the Second Punic War and the weeping of the Carthaginian senators for the loss of their liberty. Let us profit from the investment in studying this history and profit from the effort by never weeping for the loss of American liberty.

Sources:

Polybius, Histories, Book III, Section 2

Livy, History of Rome, Book XXI, Section 32; Book XXX, Sections 31,32, 44