Gas is getting expensive again. A year ago, according to AAA’s Daily Fuel Gauge Report, the price of a gallon of regular unleaded was $2.051. That was a reasonable price, one, relatively speaking, that did not hurt American pocketbooks.

That’s no longer true. Since then prices have risen dramatically. Currently, AAA reports that the average price for a gallon of regular unleaded has hit $2.85. Of course, it could be worse. Just take a look across the Atlantic. In the UK, gas prices have reached truly terrifying levels. According to London’s Daily Express: “Unleaded hit an average of 119.9p a litre for the first time ever, breaking the previous July 2008 record of 119.7p. But some forecourts are already charging 131.9p a litre – just a penny short of the £6 gallon.”

To relate this to prices in the U.S., head over to a site like this one that converts currencies and you’ll quickly find that £6 works out to $9.22. Imagine filling up a big SUV in London — filling the 28-gallon tank on a new Ford Expedition would set you back a whopping $258. Sobering indeed.

While the price of gas in the UK makes $3 gas in the U.S. suddenly look much more appealing, it doesn’t mean that Americans shouldn’t be alarmed by rising gas prices. In fact, rising prices on fuel should have Americans very alarmed. UC-San Diego economist James D. Hamilton puts the situation into perspective:

Americans buy a little less than 12 billion gallons of gasoline in a typical month. With gas prices now about a dollar per gallon higher than they were a year ago, that leaves consumers with $12 billion less to spend each month on other things than they had in January of 2009.

He goes on to note that because prices are still about a dollar lower than they were at their peak in 2008, we really don’t have to worry about this missing $12 billion.

This might be true, if the rising price was being caused by increased demand for fuel, or conversely, by decreased supply. Neither of these, however, seem to be the case. On the supply side, U.S. stocks are way up. On April 9, Myra P. Saefong of the Wall Street Journal’s “MarketWatch” site reported: “Oil’s moves leave traders scratching their heads.” As well they might because, as an Energy Department report she cited put it, U.S. crude inventories are “above the upper limit of the average range for this time of year.”

Saefong also cited energy economist James Williams who pointed out: “petroleum stocks of crude oil, gasoline, jet fuel, and distillates are all above the high end of the normal range.” Moreover, Williams also noted that OPEC has “plenty of spare production capacity.” Clearly, there is no shortage of fuel.

The demand side is less clear, but reports indicate that it remains weak. On April 12, the South Florida Business Journal noted that “crude oil demand continues to be weak….” This follows the March 12 report of the International Energy Agency that found “higher-than-expected non-OECD data, which largely offset persistently weak OECD readings.” In other words demand has been largely flat overall.

Weak demand in the U.S. on April 12 actually pushed the price of a barrel of oil lower by 58 cents. Not much, but according to MF Global energy analyst Mike Fitzpatrick, “The sentiment pendulum has shifted temporarily back towards skepticism that demand has not sufficiently recovered to support current prices.”

With strong supply and weak demand, shouldn’t prices at the pumps be falling instead of increasing? Because it seems that they should be falling, it becomes easy to find a scapegoat among the oil companies and suggest that they are artificially holding the price at the pumps high in order to maximize profits at the expense of the consumer during the beginning of the summer driving season.

But it’s too easy to assign blame to the corporate sector when there is another player at the pump: the government.

There are both obvious and less than obvious ways government has a negative impact on fuel prices. First and most obviously, government restricts access to U.S. based natural resources. Consider that now the Obama administration has announced plans to open up more off-shore areas for exploration and drilling. That sounds great, except that it was government that had those areas locked away in the first place. Moreover, as Texas Congressman Ron Paul trenchantly observed, “it is too little, much too late to have any meaningful or long-term effect on what Americans pay at the pump….”

By restricting access to domestic resources, the government has delivered the American public into the hands of OPEC, a cartel of not entirely friendly nations that controls pricing via production levels.

Given that supply is at high levels currently, OPEC can’t be blamed for high prices currently, so we have to look further into government activity. The next rock to turn over is regulation.

There is a patchwork of regulation stemming from the Clean Air Act that requires refiners to make a variety of special gasoline blends. A 2005 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that “there were at least 45 different kinds of gasoline produced in the United States during all of 2004.” This supposedly leads to cleaner air through reduced emissions. “The extent of reductions remains uncertain,” the GAO reported. For this uncertainty, however, we trade production efficiency and create costly problems. According to the GAO:

The proliferation of special gasoline blends has put stress on the gasoline supply system and raised costs, affecting operations at refineries, pipelines, and storage terminals. Once produced, different blends must be kept separate throughout shipping and delivery, reducing the capacity of pipelines and storage terminal facilities, which were originally designed to handle fewer products. This reduces efficiency and raises costs.

The use of these boutique fuels definitely leads to seasonal volatility in prices at the pump. But in the current price rise, a new factor appears to be at play: fear of fiat money.

The dollar has weakened substantially over the past decade, primarily due to Federal Reserve polices that have sought to keep interest rates low. This contributed to the housing boom and bust and the current recession. Nonetheless, the Fed loose money policy has continued, keeping the economy unnaturally inflated. Consider that in the current recession consumer spending has declined significantly, representing a reduction in demand for goods and services. This should represent deflationary pressure on pricing, but in contrast, we’ve seen just the opposite.

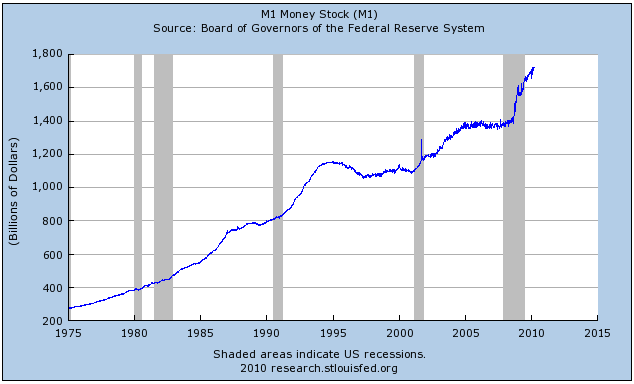

Keeping prices inflated is a function of the money supply in a fiat-money economy. And, in fact, there has been a steady trend of increases in the money supply, with a significant jump in M1 in recent months (see chart from the Federal Reserve below).

Inflation, however, is not the natural response to the current situation. Economist Peter Schiff, who perhaps more than anyone else has been prophetically forecasting the economic problems of the past few years, recently pointed out that deflation, rather than inflation, is what is needed to help the economy. In his blog on for April 12, he writes:

We need deflation. As a result of a phony boom in assets, prices levels are still too high relative to the earning power and productivity of American workers. Falling prices will cushion the blow of recession (by allowing people to buy more with their paychecks and savings) and will eventually encourage people to spend when prices fall low enough. Deflation is the only way to save us from the much greater horror of inflation, or hyper-inflation….

Inflation can’t save us from lower real wages and falling living standards, it will simply change the manner in which we are impoverished. With deflation, workers’ wages fall; with inflation, consumer prices rise. Deflation hurts, but inflation can spiral out of control, especially with an Administration addicted to spending.

As an interesting side note, the M1 multiplier, in the words of some economists has “crashed.” The multiplier, essentially, measures the effect of Fed monetary policy. Writing for iStockAnalyst, Brian Kelly describes it this way: “A multiplier is calculated simply by dividing either M1 or M2 by the monetary base. In this way, the impact of monetary policy can be measured. For example, a multiplier reading of 2.0 would indicate that for every dollar the Fed puts into the system two dollars are created. Therefore, the higher the number the more sensitive the gas pedal.”

The multiplier has dipped below the 1.0 level, indicating a strong deflationary signal despite M1 growth. But why? As it turns out, this is also a string being pulled by the Fed. There is an ongoing effort to shore up the banks, encouraging them to raise their capital ratios. In other words, the banks are beginning to hold dollars in the form of excess reserves. Moreover, lending is at relatively low levels (corresponding to low consumer demand), with the end result being that inflationary dollars are not reaching the market. This accounts for the crash of the multiplier.

But taken as a whole, this also points to volatility in the fiat currency, the U.S. dollar. And if the dollar is not necessarily a safe bet, why not invest in commodities that retain value? That’s been behind the high price in gold. Apparently it is also behind investments in oil.

This was noted by Tom Kloza, chief oil analyst with the Oil Price Information Service. Increases in price in 2010 have been “thanks to financial money managers embracing crude oil as an asset class,” he said according MarketWatch’s Saefong. Joining him was Patrick Kerr, managing director at Amerifutures Commodities & Options. Summarizing Kerr’s opinion, Saefong said he pinpointed, among other factors, that oil has been impacted by “a lack of substantial alternatives and the diversification out of fiat currencies into hard assets.”

All of the foregoing can be boiled down to a simple formula of sorts. The impetus for increasing prices, whether for fuel or anything else, is largely to be found not in the operation of the market, but in the policies and regulations of economic and other policies followed by government.

Given the dislocations of the recent past, and the continued shaky economic future, perhaps it is time to consider a return to limited government and the unfettered operations of a market economy, rather than to continue to trust in the power and wisdom of bureaucrats, planners, regulators and politicians in Washington.

Dennis Behreandt is a contributor to The New American magazine. Visit his blog and archives here.