S&P said: "Progress [in] containing the growth of public spending, especially on entitlements, or on reaching an agreement on raising revenues, is less likely than we previously assumed…. The fiscal consolidation plan [Budget Control Act of 2011] that Congress and the Administration agreed to this week falls short of the amount we believe is necessary to stabilize the general government debt burden…. Elected officials remain wary of tackling the structural issues required to effectively address the rising U.S. public debt burden in a manner consistent with a ‘AAA’ rating." (Emphases added.)

In other words, the Sturm und Drang masquerading as serious discussions that had virtually taken over the conversation in Washington for the past weeks has generated nothing substantial — at least nothing substantial enough to keep S&P from doing exactly what it warned it would do back in June: “If we conclude that Congress and the Administration have not achieved a credible solution to the rising US government debt burden and are not likely to achieve one in the foreseeable future, [then] we may lower the long-term debt rating on the US by one or more notches into the AA category.”

Which is exactly what it did, along with noting that its “negative watch” means a further downgrade is possible within the next two years. At present, the AA+ rating on the country’s sovereign debt is now on a par with Belgium and New Zealand, and is lower than a dozen other countries that still enjoy a AAA rating from S&P. Any delay in a further downgrade would be based on real reductions in government spending and improvements in the country’s economic outlook, neither of which, at the moment, is likely.

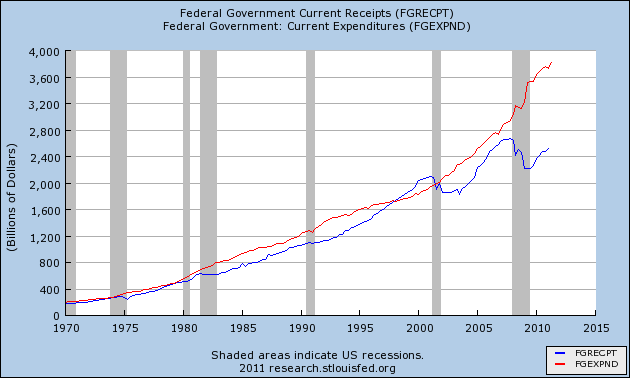

Here is what the rating agency is looking at:

(Blue line shows federal govt. receipts & red line expenditures; source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

The United States has been living on borrowed time. Taking full advantage of the fact that the dollar has been the world's reserve currency and that China and others have accepted dollars in exchange for their goods, the United States has been able to expand government spending and print more money with relatively little negative ramifications. But this cannot continue indefinitely — particularly considering that the spending-revenue gap, exacerbated by a recession, has grown alarmingly during the Bush and (more obviously) Obama administrations.

Making matters worse, the debt deal signed into law by President Obama on Tuesday does not even cut government spending in the real sense. The purported cuts are actually cuts in projected future increases. Government spending is still projected to go up, but not as much as otherwise.

That is why the S&P says that it is “pessimistic about the capacity of Congress and the administration to be able to leverage their agreement this week into a broader fiscal consolidation plan that stabilizes the government’s debt dynamics anytime soon.” That’s economic-speak for: the Budget Control Act of 2011 is a farce, and S&P sees little hope of things changing anytime soon.

The other two debt-rating agencies, Moody’s and Fitch Ratings, still consider U.S. debt as AAA, but each is watching the situation closely, with Moody’s preparing to give its opinion at the end of the month. Moody’s mouthpiece, Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, says that “U.S. Treasuries are still the gold standard.”

What is the immediate impact of the downgrade? In the short run, analysts are holding to the opinion that little will change. The downgrade will affect those institutions with direct and indirect links to the U.S. government, such as states and municipalities holding Treasuries in their accounts. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will also be downgraded, as will other financing arms of the government. The immediate impact will be minimal, with interest rates likely to rise perhaps one-half of one percent over the next month or so. And investment agreements of insurance companies and pension funds requiring AAA holdings as part of their portfolios will merely change the language in those agreements to allow for the inclusion of U.S. sovereign debt regardless of the lack of the AAA rating. It’ll be easier to change the language than to flood the market with government bonds.

But in the longer term the downgrade by Standard and Poor’s may be viewed as the beginning of a “death spiral,” where interest rates begin to climb to the point where a significant part of the revenue stream is required just to service the debt. Interest rates on mortgages, auto loans, and other types of lending will slowly increase, reducing inevitably the amount of borrowing. This will continue to slow economic growth, with JPMorgan estimating that an increase in interest rates of 50 basis points (one-half of one percent) would reduce the US’s economic growth by about 0.4 percentage points. With the economy stalled, that could be the straw that pushes the economy into negative territory, triggering the feared “double dip” recession.

The “death spiral” could begin as the economy continues to slide into recession, generating less and less revenue, while government spending continues and accelerates. As interest rates rise (to compensate bond holders for the additional default risk), the economy is less and less able to service the debt. As Chief Executive Officer Mohammed Al-Erian of PIMCO, the world’s largest bond management company, noted in a Bloomberg Television interview, “The minute you start downgrading away from AAA, you take small steps toward credit risk and that is something any country would like to avoid.” At the moment, debt service on the nearly $15 trillion of debt the government has issued is $414 billion annually. If interest rates do rise, as many are anticipating as a result of the downgrade, by just one-half of one percent, that will increase that debt service by $100 billion, an increase of nearly 25 percent in just one year.

Another impact of the downgrade is the inevitable loss of confidence in the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. That loss of confidence is already showing up as the world’s portion of dollars held as reserves is dropping, down from 72.7 percent in 2001 to just 60.7 percent at the end of March. The Treasury Borrowing Committee (TBAC), which advises the U.S. Treasury, noted in a presentation on Wednesday, “The fact that [at present] there are not currently viable alternatives to the U.S. dollar is a hollow victory and perhaps portends a deteriorating fate.” The TBAC presentation added, “The idea of a reserve currency is that it is built on strength, not typically that it is [the] ‘best among poor choices.’”

Commenting on the downgrade, the National Inflation Association said they believe “that a AAA rating should be reserved for countries that have budget surpluses, low levels of debt that could easily be paid off without printing money, and low levels of inflation…. If it wasn’t for our printing press and the world’s willingness to accept and hoard the dollars we print in return for the real products and commodities they produce, the U.S. credit rating would be junk.”

The ultimate determinant of the value of government debt, however, will not be made by what rating agencies think, but by consumers in the economy making economic decisions in light of their own self-interest. It is revealing that according to Rasmussen Reports their Consumer Index (which measures the economic confidence of consumers on a daily basis) just reached a two-year low on Thursday, while their Investor Index fell to a new two-year low last Saturday. And these polls were taken before S&P downgraded U.S. government debt.

Photo: New York Stock Exchange