On March 12, 1932, French police discovered a man dead of a gunshot wound in a sumptuous apartment on Avenue Victor Emanuel III in Paris. After a thorough investigation, it was determined that the man, a middle-aged Swedish businessman, had died of a self-inflicted shot from a 9 mm pistol. The man’s name was Ivar Kreuger.

Nowadays, the name of Ivar Kreuger is remembered by very few, but in the early thirties, the flamboyant Swedish businessman and financier was the toast of investors and bankers in both Europe and the United States. Kreuger, who was known as the “Match King,” had built his fortune in the then-fledgling match industry. At the height of his influence, he controlled an estimated three-quarters of the world’s match manufacturing. Kreuger maintained six or seven homes on two continents, including three mansions in Sweden, a permanent suite at the London Carlton, and apartments in Berlin, New York’s Park Avenue, and the Avenue Victor Emanuel III in Paris. At his Parisian lodging, he entertained an unending parade of mistresses that included Parisian shop girls, students, and streetwalkers.

Not content merely to manufacture “lucifers,” as they were then sometimes called, Kreuger diversified his portfolio to eventually acquire some 200 different corporations. He also was lauded for extending huge loans to many governments foundering in the uncertain financial waters of the postwar 1920s.

Kreuger was credited for single-handedly rescuing the likes of Poland, Greece, Ecuador, Guatemala, Hungary, Latvia, and Romania from outright bankruptcy, and with helping many others, including France and Germany, survive the turbulent period. He usually required that countries who benefited from his largesse, including France and Germany, return the favor by granting his matches preferential trade status. Of the Germans, he even stipulated that they ban all imports of matches from Russia, one of his major competitors.

Kreuger also capitalized on his larger-than-life reputation to issue large amounts of debentures, or unsecured long-term corporate debt, to thousands of Swedish investors. These so-called “Kreuger papers” were extremely popular, since it was widely believed that the Kreuger financial empire was on very solid footing.

Events in the early thirties changed all that. The collapse of markets all over the world laid bare balance-sheet weaknesses far and wide. Banks and huge numbers of other corporations that had failed to save for a rainy day, relying instead on the unwarranted belief that unending growth would overwhelm shaky assets or excessive leverage, failed spectacularly.

In a climate of renewed financial vigilance, banks and other creditors began examining Kreuger’s activities in more detail. As suspicions mounted that the Match King’s financial house was built on sand, banks became reluctant to extend further credit. After Kreuger failed to convince the Sveriges Riksbank, the Swedish central bank, to extend an emergency loan (what would now be called a bailout), Kreuger knew the game was up and apparently took his own life rather than face scandal and ruination. (There remain some doubts that Kreuger’s death was suicide, but since he was cremated immediately and the gun that took his life disappeared, the truth will never be known).

When the balance sheets of the hundreds of Kreuger enterprises were examined, it quickly became apparent that Kreuger had for years been running a vast Ponzi (pyramid) scheme. The Kreuger papers and other debts supposedly guaranteed by Kreuger’s assets became worthless overnight when it was revealed that most of his companies had negative worth. The man who has been called “the prince of the first global finance state” had been exposed as an utter fraud.

The collapse of the Kreuger empire had far-reaching consequences, causing the so-called “Kreuger crash” that affected thousands of banks and investors, especially in Sweden and the United States. In the larger context of the Great Depression, however, the Kreuger affair proved to be a flash in the pan, and Kreuger himself merely the gaudiest of a generation of financial hucksters who had built phantom fortunes in the inflationary economy of the Roaring Twenties. In all, Kreuger’s activities cost banks, investors, and governments hundreds of millions of dollars — a very formidable sum indeed by the standards of the early thirties.

Fast Forward to Today

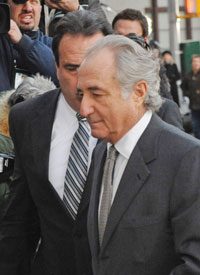

On December 10, 2008, prominent investor, philanthropist, and former chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange Bernie Madoff sat down with his two sons Mark and Andrew to confess to them that the asset management arm of his firm Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC was nothing but “a big lie.” For decades, Madoff had been trusted with the assets of many of the world’s wealthiest and best-connected individuals, charitable foundations, banks, and investment firms. Now, he told his sons, the game was up, and he wanted to make a full breast. The following day, his sons reported their father’s confession to the authorities, and Madoff was taken into custody by the FBI and charged with securities fraud.

As the extent of the Madoff Ponzi scheme came to light, Wall Street learned that one of its own was responsible for hundreds of billions of dollars in stolen assets. The Madoff affair could scarcely have come at a worse time, with markets already reeling from the severest global downturn since the Great Depression. Many institutions with a large exposure to Madoff’s scheme, like European banking giant Banco Santnader, suffered huge losses, and at least two destitute clients chose to commit suicide. As with the Kreuger affair almost 80 years earlier, the man on the street marveled that one con artist could have gotten away with so much for so long.

Madoff, in contrast to Kreuger, led a superficially down-to-earth life. The son of hardworking Eastern European immigrants, Madoff started his professional life as a plumber. He began his career in finance as a penny stock trader in 1960, using money saved while working as a lifeguard and sprinkler installer. Married for decades to his high-school sweetheart, Madoff donated widely to a large number of charities, and sat on the boards of many of the nonprofit organizations he founded or helped to fund.

But evidence now being uncovered shows that, for decades, the munificent Madoff led a double life, stealing investors’ assets and chalking up tens of billions of dollars of non-existent investor assets. Yet in spite of the duration of the fraud — and years of warnings to federal authorities by an astute financial analyst, Harry Markopolos, who began telling the SEC a decade ago that Madoff’s claimed assets were obviously bogus — it was Madoff’s own confession, prompted, perhaps, by a burden of guilt, that finally exposed the charade.

We would do well to wonder how it is that, in our day of supposedly seamless government vigilance over the activities of investors, the U.S. financial sector could be rocked by two gigantic scandals (Enron, of course, was the first) in a single decade. The vaunted SEC, founded in the early thirties in no small measure because of the Kreuger affair, is supposed to nip fraud in the bud, shining the light of day on otherwise secretive brokers and financiers, and creating a climate of transparency that would deny the Madoffs of the world cover for their dishonest ambitions.

Yet, as both the Madoff and Enron scandals have made clear, we are no less vulnerable today than was the world in Ivar Kreuger’s time. The parallels between the two men, in fact, are striking: both operated in times of irrational economic exuberance created by the expansionary policies of central banks like the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. As in the Roaring Twenties, so too in the Roaring Eighties and Nineties: easy-money policies brought about by artificially depressed interest rates encouraged a bacchanal of debt, a disdain for savings, and an appetite for risk that overwhelmed the sober wisdom of more prudent generations. In such a climate, individuals and institutions were eager to put their money in what in saner times would be deemed very risky places. Everybody was making money, and no one believed that a day of accounting would ever come.

But the mania of artificial economic booms eventually cools, and with it, more sober counsels prevail. In Ivar Kreuger’s case, the contraction of global finances eventually forced his hand. In Madoff’s, the economic downturn probably persuaded him to come clean, knowing he could not conceal his wrongdoing much longer.

Let the Buyer Beware

As the Madoff case shows, federal oversight of the market is no guarantee of protection against endlessly inventive scam artists. The Madoff scandal, in point of fact, may have been made worse precisely because investors, already giddy from market gains, consoled themselves that the federal government — the SEC in particular — would safeguard them from being victimized by large-scale fraud.

In reality, reliance on free-market forces rather than government regulation and oversight is a far sounder way to protect the market against fraud. If individuals and firms must judge for themselves the soundness of an investment, they will be far more vigilant, or less willing to put all their eggs in one basket, if they know they must assume the risk of being defrauded. Caveat emptor works as well with investment portfolios and bank accounts as with used cars.

But if investors expect the government to do due diligence for them, they are far less likely to concern themselves with the balance sheets of the investment houses and banks where they place their hard-earned money. The SEC has proven to be a burdensome failure, thanks to the Madoff scandal, yet the Obama administration, undeterred by the spectacular failure of government regulatory intervention in the markets, is proposing more, not less, market regulation as the solution.

But the real rub of the twin sagas of Ivar Kreuger and Bernie Madoff is that both men, in misrepresenting their assets and using debt to conceal debt, have had the misfortune of being private citizens brought down for doing precisely what governments, thanks to the legerdemain of central banking, do as a matter of course.

This is an obvious point that the news media, in condemning Bernard Madoff, have refused to acknowledge. For if the Madoffs and the Kreugers of the world are guilty of operating fraudulent Ponzi schemes (and they most certainly are), the governments that prosecute them are guiltier still. Even as Madoff — who has at least acknowledged his guilt and will pay for his crimes — is pilloried by the media and prosecuted by the state, the mandarins at the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve continue to try to stave off the fact of impending national insolvency by printing money and issuing horrendous amounts of new debt that will never, ever be repaid. The entire United States federal government, addicted to deficit spending, is operating the largest Ponzi scheme the world has ever seen, defrauding not merely a few investors but every U.S. citizen and every institution, public or private, on the face of the Earth that holds U.S. government debt.

This is so because the money that the U.S. government uses to pay its obligations — the U.S. dollar — loses value constantly thanks to the activities of the Federal Reserve. The effects of this inflation (artificial expansion of the money supply) are higher prices and the gradual erosion of the value of savings. This means that Treasury bonds and bills — instruments of debt which the government pledges to repay — will be redeemed in depreciated dollars, effectively defrauding holders of government debt. It is thus ironic that, even as Bernie Madoff is rhetorically and prosecutorially hung in effigy, the Federal Reserve has expanded the money supply by about $1.2 trillion, which will trigger a calamitous decline in the value of the dollar in the not-too-distant future.

Whether or not government imposes its heavy hand on financial activity, scam artists large and small will always be with us. But in a day when the government is expected to be intimately involved in the marketplace, the reality of fraud and scandal will actually be greater, and not only because the Bernie Madoffs of the world will find ways to operate under the radar screen.

It is a harsh but unavoidable truth that the entire basis for our modern financial system — the U.S. dollar — is fraudulent, a gigantic confidence game from which no one not living a subsistence lifestyle in the forests of Amazonia or Papua New Guinea is protected. For on the day the dollar Ponzi scheme comes apart, the day people realize that the U.S. government never intends to repay its debts or can’t repay its debts, triggering an unprecedented global currency crisis and the end of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, the misdeeds of the Madoffs and Kreugers — penny ante players by comparison — will seem almost forgivable.

— Photo: AP Images