When Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke speaks on Friday at the Fed’s annual meeting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Fed-watchers from around the world will be hanging on his every word, phrase, and nuance for clues. They’ll be listening to hear that the chairman knows what’s happening in the economy, and that if things get worse, he has a plan.

The economy continues to suffer as shown by weak demand for housing, high unemployment, and declines in hard goods manufacturing. As Randall Forsythe put it, “Every data point on employment and housing since midyear has fallen short of expectations, in some cases, far short.” The numbers just

released by the National Association of Realtors for July were horrific, despite the Fed’s efforts to “re-flate” the housing market, as Tom Eddlem pointed out.

And it’s foolish to look for a recovery in housing without a recovery in employment. As noted here there are three main reasons why housing isn’t likely to rebound anytime soon: 1) There is a mountain of unsold homes on the market, more than a year’s supply; 2) There aren’t enough qualified buyers trying to purchase a home right now; and 3) bankers are still holding onto their cash, preferring to keep it invested in risk-free Treasuries.

Michael Feroli of JP Morgan Chase said that July’s durable goods report on Wednesday was “disastrous,” with “core” capital goods off 8 percent in one month and the most since January, 2009. Looking forward, he said that business capital spending looks “atrocious,” while Nouriel Roubini,the New York University economist, expects that growth next quarter will be “well below” 1 percent, adding, “With growth at a stall speed of 1 percent or below, the stock markets could sharply correct … [creating] a negative feedback loop between the real economy and … risky asset prices [that could] easily then tip the economy into a formal double-dip.” David Wyss, chief economist at Standard & Poor’s, agrees with Roubini: “The economy is surely not in good shape — the odds of a double dip are a long ways from zero.”

The trouble is that policymakers themselves are divided about what to do. The Washington Post pointed out that the Fed’s policy intentions “have been unusually muddled in the past two months,” and according to the view shared by many mainstream economists, “it is unclear how likely it is that the Fed will undertake major new efforts … [or] what form those actions would take.”

Those attending the conference have differing opinions. President of the St. Louis Fed James Bullard said that the Fed should consider pumping additional billions of dollars into the moribund economy, while Kansas City Fed chief Thomas Hoenig says the Fed should raise interest rates to choke off incipient inflation. Most of them, however, favor muddling through, taking a wait-and-see attitude.

What are the Fed’s options? At bottom, the Fed can do only two things: speak, and print. If the Fed follows Bullard and expands the money supply even further (inflation), rising prices will eventually be the result. Some will say that a cheaper dollar will make American goods look cheaper abroad, which will stimulate exports. But the long term course of that policy is the ultimate destruction of the dollar. If the Fed follows Hoenig and stops the printing press, the resultant rise in interest rates will add another burden to the struggling economy.

Some Fed people admit that they don’t know what to do. Dennis Lockhart, president of the Atlanta Fed, just trusted his gut when the Fed’s balance sheet started shrinking because of mortgages being paid off due to refinancings. Said Lockhart, “The shrinking of the balance sheet just didn’t feel right to me under the circumstances.” (Emphasis added.)

And equivocating isn’t good either. Fed governor Kevin Warsh argued that an abrupt change in either direction would spook the markets since the public would believe that the Fed is more worried about the economy than it is letting on. This may explain the nervousness shown by investors of late. As David Callaway succinctly put it, “If this group can’t tell whether we’re headed for Japanese-style deflation or German-style hyperinflation, then investors certainly don’t want to be in the game at all.”

Hans Sennholz claimed that “faith in the Fed” to know what it is doing is not only foolish but dangerous.

It is the federal moneybag which can finance any government expenditure and come to the rescue of any number of banks and financial institutions, it can create new money with the speed of a computer command and transfer it in seconds by high-speed modem. It can create deposits of one dollar as efficiently as it can create one million, one billion, or even one trillion dollars. The Fed derives this magical power from its position as money monopolist, from the legal tender force of its money, and from its regulatory powers over financial institutions. Its power is purely political, created and granted by the United States Congress, sanctioned by the courts, and enforced by the police….

When the Chairman speaks, the financial world holds its breath….

Most economists view the vast powers of the Fed with favor and applaud its managers. Unfortunately, they seriously overestimate the Fed’s power and take no heed of the fateful role played by the Fed. Their blind faith in political power cannot bear to look.

On Friday, the chairman will use one of the only two tools the Fed has at its disposal: words. In a rational, free-market world, Bernanke would be sight-seeing in Jackson Hole, and nobody would care. And the free market would determine the the value of money, with no one granted monopoly power to create it out of thin air.

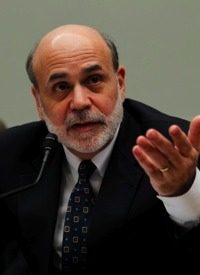

Photo of Bernanke: AP Images