Last month’s vote by the United Kingdom to withdraw from the European Union not only sent shock waves throughout the world, but doubled down on a theme resonating loudly in the United States: the curtailment of unrestrained globalism.

Like all themes, the picture is painted with a broad, diffuse brush. The Brexit vote was tight, with 51.9 percent casting “leave” ballots and 48.1 percent wishing to remain in the EU, signifying — as in the United States — a divided population. Some believe exiting the union represents a clear opportunity for long-term growth and new, advantageous trade deals, while others fear retrenchment and marginalization of British influence in Europe.

Regardless, the impacts of Brexit are certain to affect the United States now and down the road. On balance, will it be a net positive for the U.S. economy?

Globalization

Let’s start with what the term “globalization” means. Per Investopedia:

Globalization is the tendency of investment funds and businesses to move beyond domestic and national markets to other markets around the globe, thereby increasing the interconnection of the world. Globalization has had the effect of markedly increasing international trade and cultural exchange.

With the advent of the Internet and following the rise of global inter-connectivity, the growth of international trade has trended upward for the better part of the last two decades. While many of the effects of said growth have been positive, there is a dark side to globalization: resource allocation shifting to cheaper venues.

The Purpose of the European Union

The European Union officially came into existence on November 1, 1993. Investopedia defines its fundamental purpose in the following passage:

The European Union (EU) is a group of 28 countries that operates as a cohesive economic and political block. Nineteen of the countries use the euro as their official currency. The EU grew out of a desire to form a single European political entity to end the centuries of warfare among European countries that culminated with World War II, which decimated much of the continent. The European Single Market was established by 12 countries in 1993 to ensure the so-called four freedoms: the movement of goods, services, people and money.

In some ways, the EU appeared to contribute toward the stabilization of Europe. Movement of goods, services, people and money was, for the most part, simpler. With that said, economic prosperity trumps all, and to that end, the net impact of the EU was decidedly negative for Great Britain.

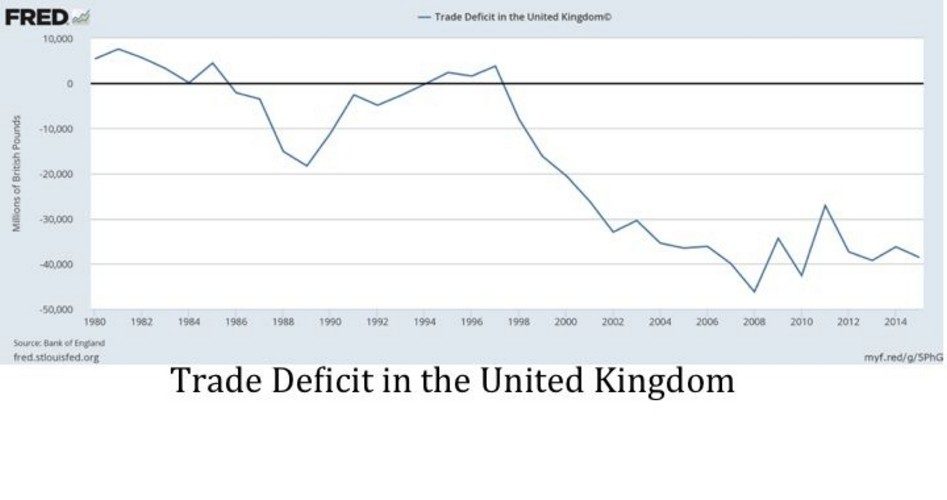

Britain’s Trade Deficits

The European Union was a big step in Great Britain’s globalization. And although British exports did rise, imports increased even more quickly.

At the time the EU was formed, Britain was emerging from the early 1990s recession, posting a small trade deficit (£185 million) in 1994. After generating surpluses the next three years, its balance of trade fell through the floor, bottoming out at £46.2 billion by 2008. At the end of 2015, it remained in the cellar, recording a deficit of £38.6 billion.

How do large trade deficits hurt an economy? Simply put, the consumption of internationally produced goods displaces domestic manufacturing, costing well-paying jobs. In Great Britain, manufacturing jobs fell 31.1 percent during the 1990s and have continued to decline since then.

As in the United States, GDP growth followed a similar pattern, trending downward over the past 20 years. Britain’s average growth rate has been about .5 percent slower than the tepid increases seen in the United States over the past 20 years.

Brexit’s Benefits for U.S. Trade

As with all multi-party agreements, partnerships carry the risk of systemic disadvantages. Too often, weaker partners (in the EU’s case, Greece) require propping up or bailing out, shifting resources and capital away from stronger parties. Over the long term, flaws in multiparty agreements come to light, creating a sense of unfairness that can fester before eventually boiling over. Such was the case with the Brexit referendum results.

The United States has no formal union per se, but is a signer of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a sweeping multilateral pact between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The Trans-Pacific Partnership is yet another free trade agreement under consideration, this time between Pacific Rim countries.

The most significant benefit of Brexit to the United States is the mounting pressure the next president will face to renegotiate — or possibly even scuttle — these trade agreements. As William F. Jasper of The New American wrote about the TPP back in 2013 :

It would … confer huge advantages on foreign businesses and large multinationals, while at the same time putting companies that operate here in America — especially small and medium-sized enterprises — at a competitive disadvantage. American businesses would remain shackled by the regulations of EPA, FDA, OSHA, etc. while their foreign competitors could operate here unimpeded by those same strictures.

What about NATFA? This writer discussed its deleterious impacts upon the U.S. economy in The New American two months ago:

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the average manufacturing wage was $14.55 per hour as of February 2001. Assuming a 40-hour workweek, the sector would have generated $515 billion in total salaries. Fast forward to February 2016: After adjusting for inflation, manufacturing wages are effectively at three-quarters their former level, despite an economy that is 73 percent larger. Clearly, a major drag on consumer spending — and, commensurately, glacial economic growth over the past 15 years — is the dramatic decline of manufacturing jobs in the United States.

Other Advantages

The Brexit saga carries other potential financial advantages for the United States, including:

• Stock markets: Long considered a financial “safe haven,” international turmoil and uncertainty typically benefit U.S. markets as capital flows in from around the world, pushing up values.

• Interest rates: Although long overdue for increases, the uncertainty on the world stage should keep the Federal Reserve from raising rates aggressively, keeping borrowing costs down and spurring capital investment. The negative effects of prolonged low interest rates are a discussion for another day.

• Travel: The dollar is likely to remain strong, making overseas travel cheaper.

• Nationalism: With the tide turning against rampant globalism, a renewed focus on solving domestic problems could be just what the doctor ordered for the American economy.

Of course, the formal exit of Great Britain from the European Union is still up to two years away, so anything can happen before then. As Hugh MacKay once wrote, “Nothing is perfect. Life is messy. Relationships are complex. Outcomes are uncertain. People are irrational.”

Sounds like a good summary of the upcoming presidential election.