Californians are experiencing their third year of drought. Headlines read: “Current California Drought Is Driest In State’s History; Scientists Fear ‘Megadroughts’ On Their Way.” “Global Warming Upped Heat Driving California’s Drought.” Then there are scientific claims such as, “There’s a rapidly growing body of scientific research finding that California is in the midst of its worst drought in over a millennium (and) global warming has made the drought worse.” A Stanford University study said, “Human-caused climate change helped fuel the current California drought.” One news outlet summarized the conclusions of a group of environmentalists this way: “California’s severe and ongoing drought is just a taste of the dry years to come, thanks to global warming.”

Let’s examine a few drought facts. California experienced eight major droughts in the 20th century, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. They ranged from two years to as long as nine years, such as that which occurred from 1928 to 1937. In the previous century, there was the bitter drought of 1862-65, which was a catastrophe for the state of California — made worse by a smallpox epidemic. Scott Stine — professor of geography and environmental studies at California State University, East Bay — said that all of these modern droughts were minor compared with California’s ancient droughts of 850 to 1090 and 1140 to 1320. One wonders whether California Gov. Jerry Brown and his cadre of environmental extremists would attribute those ancient droughts to man-made global warming.

A large part of California’s water problem has economic roots. Whenever there’s a shortage of anything — whether it’s water or seats at a baseball stadium — our first suspicion should be that the price is too low. California agriculture consumes about 80 percent of the state’s delivered water, and it has been exempted from many of California’s new restrictions. On top of that, agricultural water users pay a much lower price than residential users. In other words, California’s farmers are being heavily subsidized.

The Imperial Valley, located in the southeastern part of the state, is geologically a desert. Nonetheless, its farmers grow large quantities of potatoes, cauliflower, sweet corn, broccoli and onions. These crops would not be produced without there being subsidized irrigation and other state and federal subsidies. I need someone to show me that there is such a desperate need for somewhere to grow potatoes, corn and other crops that we need to subsidize making a desert bloom.

Western water is mostly controlled by the U.S. Congress and its Bureau of Reclamation. Through lobbying efforts, the Bureau of Reclamation is controlled by growers and other special interests. Water is distributed in California and other Western states not by market prices but by the political process. Agricultural interests have disproportionate political power. That means that agricultural interests receive taxpayer-financed handouts.

California farmers argue that without federal and state government subsidies, crops could not be grown in desert areas. That’s a foolish, self-serving argument. If I were an Alaskan wanting to use government subsidies to build hothouses to grow navel oranges, I could use the same argument: Without government subsidies, I couldn’t grow navel oranges in Alaska.

Some of California’s water conservation regulations are mindless. It is illegal for servers in bars, restaurants and cafeterias to serve water unless customers ask. The amount of water that people drink per day is a trivial part of total water consumption. Estimates vary, but each person consumes 80 to 100 gallons of water per day flushing toilets, bathing and for other residential purposes.

Another California water conservation effort is “drought shaming.” That’s when vigilantes call water utility hotlines to snitch on their neighbors who are watering lawns, washing cars or filling pools. One wonders whether there might arise an anti-vigilante movement to punish the vigilantes.

The bottom line for solving California’s water problem is that there needs to be a move toward a market-oriented method for the distribution of water. Government management has been a failure.

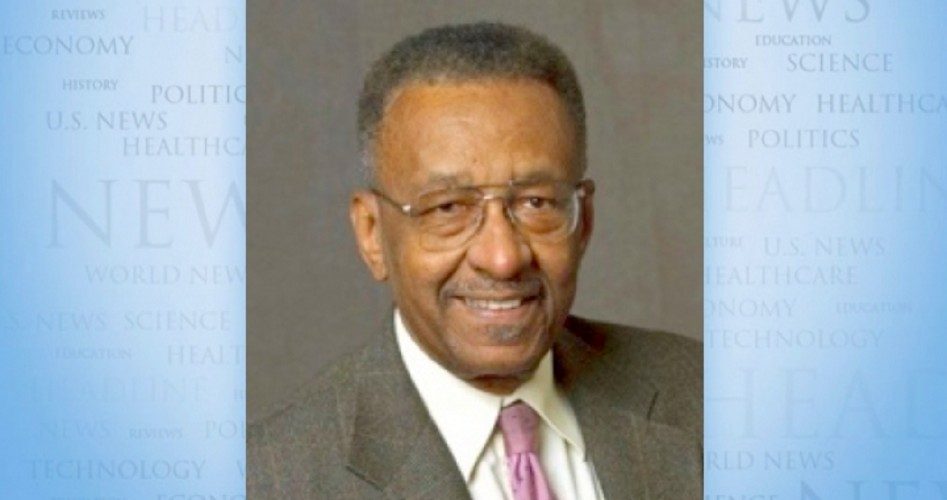

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM