In a March 2008 column, I criticized pundits’ concerns about whether America was ready for Barack Obama, suggesting that the more important issue was whether black people could afford Obama. I proposed that we look at it in the context of a historical tidbit.

In 1947, Jackie Robinson, after signing a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization, broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball. He encountered open racist taunts and slurs from fans, opposing team players and even some members of his own team. Despite that, his batting average was nearly .300 in his first year. He led the National League in stolen bases and won the first Rookie of the Year award. There’s no sense of justice that requires a player be as good as Robinson in order to have a chance in the major leagues, but the hard fact of the matter is that as the first black player, he had to be.

In 1947, black people could not afford an incompetent black baseball player. Today we can. The simple reason is that as a result of the excellence of Robinson — and many others who followed him, such as Satchel Paige, Don Newcombe, Larry Doby and Roy Campanella — today no one in his right mind, watching the incompetence of a particular black player, could say, “Those blacks can’t play baseball.”

In that March 2008 column, I argued that for the nation — but more importantly, for black people — the first black president should be the caliber of a Jackie Robinson, and Barack Obama is not. Obama has charisma and charm, but in terms of character, values, experience and understanding, he is no Jackie Robinson. In addition to those deficiencies, Obama became the first person in U.S. history to be elected to the highest office in the land while having a long history of associations with people who hate our nation, such as the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s pastor for 20 years, who preached that blacks should sing not “God bless America” but “God damn America.” Then there’s Obama’s association with William Ayers, formerly a member of the Weather Underground, an anti-U.S. group that bombed the Pentagon, U.S. Capitol and other government buildings. Ayers, in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attack, told a New York Times reporter, “I don’t regret setting bombs…. I feel we didn’t do enough.”

Obama’s electoral success is truly a remarkable commentary on the goodness of the American people. A 2008 NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll reported “that 17 percent were enthusiastic about Obama being the first African American President, 70 percent were comfortable or indifferent, and 13 percent had reservations or were uncomfortable.” I’m 77 years old. For almost all of my life, a black’s becoming the president of the United States was at best a pipe dream. Obama’s electoral success further confirms what I’ve often held: The civil rights struggle in America is over, and it’s won. At one time, black Americans did not have the constitutional guarantees enjoyed by white Americans; now we do. The fact that the civil rights struggle is over and won does not mean that there are not major problems confronting many members of the black community, but they are not civil rights problems and have little or nothing to do with racial discrimination.

There is every indication to suggest that Obama’s presidency will be seen as a failure similar to that of Jimmy Carter’s. That’s bad news for the nation but especially bad news for black Americans. No white presidential candidate had to live down the disgraced presidency of Carter, but I’m all too fearful that a future black presidential candidate will find himself carrying the heavy baggage of a failed black president. That’s not a problem for white liberals who voted for Obama — they received their one-time guilt-relieving dose from voting for a black man to be president — but it is a problem for future generations of black Americans. But there’s one excuse black people can make; we can claim that Obama is not an authentic black person but, as The New York Times might call him, a white black person.

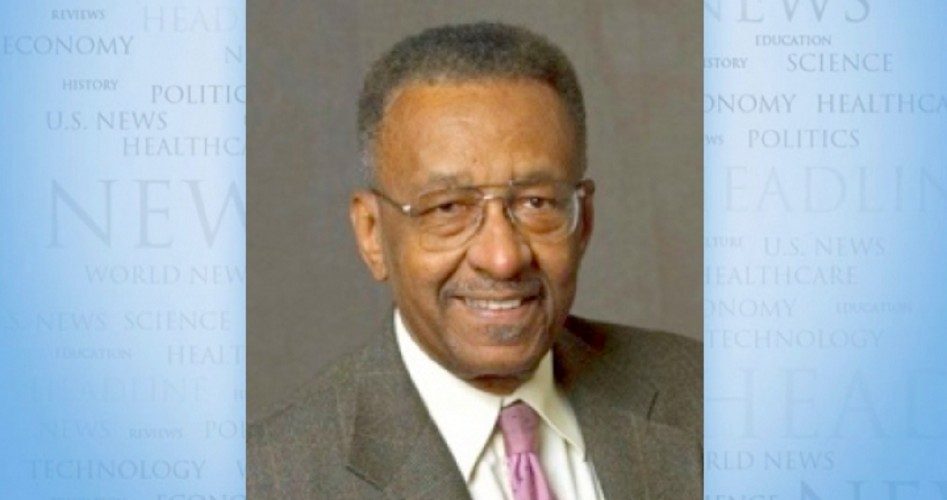

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2013 CREATORS.COM