Trying to choose the greatest pitcher of all time is at least as difficult as trying to choose the greatest hitter of all time. In both cases, the best we can do is narrow down the list.

Outside a charmed circle of five batters, no one had both a higher lifetime batting average and a higher lifetime slugging average than any of those five. In alphabetical order, they are Ty Cobb, Lou Gehrig, Rogers Hornsby, Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. There are other batters whose lifetime records came close, including Barry Bonds, Jimmie Foxx and Hank Greenberg. But close cannot define the greatest.

When it comes to choosing the all-time greatest pitcher, there are even more complications than there are in choosing the candidates for the all-time greatest batter. Batting is much more of an individual achievement, while a pitcher’s record depends on what his team does, both at bat and in the field.

A great pitcher who is pitching for a team that scores very few runs may have a tougher time winning games than a pitcher who gives up an average of 3 runs a game, but who is pitching for a team that scores an average of 5 runs a game for him.

When a pitcher has a great double-play combination behind him at shortstop and second base, or a Willie Mays or Joe DiMaggio in center field, that can also keep his earned run average down.

With pitchers, as with batters, a spectacular season should not carry as much weight as a whole career of great achievements. Back in the early 20th century, there were a couple of 40-game winners, and 37-game winner Iron Man McGinnity on several occasions pitched both games in a double-header. But pitching a lot of games in a season was not a formula for longevity.

On the other hand, total wins in a lifetime cannot be the sole criterion, since that obviously depends on longevity as much as on pitching effectiveness. Weighing strikeouts against earned run averages can also vary from one observer to the next.

Since the ultimate purpose of pitching is not simply to strike out batters but to keep the other team from scoring, I would give a lot of weight to shutouts. Here one man stands head and shoulders above the rest.

Walter Johnson is the only pitcher to pitch more than a hundred shutouts in his career — 110, in fact. Playing for a team that was not always among the best, more than one-fourth of his 416 career victories were shutouts.

With even the greatest pitchers of our era seldom going the full nine innings, Walter Johnson’s 110 shutouts seems to be the baseball record least likely to be broken. In order to compare the pitchers of our time with those of the past, earned run averages may have to be used.

Walter Johnson’s lifetime earned run average was 2.17. Christy Mathewson had a lifetime ERA of 2.13, but Mathewson played for better teams. It is hard to think of any other pitcher whose lifetime records top theirs, except for records based on sheer longevity, like Cy Young’s 511 victories. Cy Young had a lifetime ERA of 2.63 — obviously great, but not the greatest.

Hard as it is to narrow down the candidates for the title of greatest batter of all time, or the greatest pitcher of all time, selecting who should be nominated as having the greatest versatility seems a lot easier.

There is only one baseball player who, at various times, led the league in both batting and pitching categories. That one man was Babe Ruth.

The Bambino had a league-leading batting average of .378 in 1924 and hit .393 the previous year, when Harry Heilmann hit .403. When it came to home runs, Ruth was the only man to lead the league in that category in 12 different seasons.

Babe Ruth’s records as a pitcher are not nearly as well known. But he led the league in ERA with 1.75 in 1916. His lifetime ERA was 2.28, putting him in the company of the greatest pitchers of all time. The Babe still holds the American League record for the most shutouts in a season by a left-handed pitcher, and holds the record for the longest shutout ever pitched in the World Series — 14 innings.

Is anyone else even close to leading the league in both of these very different and very fundamental aspects of baseball?

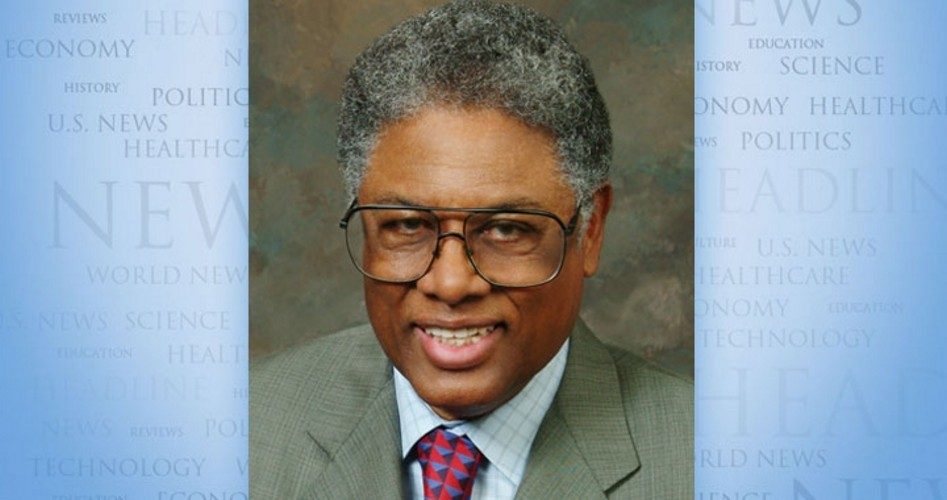

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. His website is www.tsowell.com. To find out more about Thomas Sowell and read features by other Creators Syndicate columnists and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2012 CREATORS.COM