This week marks the 210th anniversary of the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which was located in what is now Alabama — then Mississippi Territory — during the War of 1812.

While Americans rightly remember hearing about the Battle of New Orleans (perhaps because of Johnny Horton’s famous song), which made Andrew Jackson a national hero and eventually launched him into the White House, this battle, which took place months earlier, is one of the most under-rated — in importance — of battles of American history.

Unfortunately, those who read an Associated Press article about this battle, written by Kim Chandler, were given a grossly distorted version of it. Either Chandler is uninformed on the history of the battle, or she opted to deliberately write a story that is filled with half-truths, so as to advance a certain viewpoint.

Chandler’s article reads almost like a press release given to her by one side of the battle. “Prayers and songs of remembrance carried across the grassy field where more than 800 Muscogee warriors, women and children perished in 1814 while defending their homeland from United States forces,” Chandler began her piece.

“One thousand warriors, along with women and children from six tribal towns, had taken refuge on the site, named for the sharp bend of the Tallapoosa River. They were attacked on March 27, 1814, by a force of 3,000 led by future U.S. President Andrew Jackson.”

All of this is true, as far as it goes, but Chandler’s version of events lacks historical context, and omits very important facts.

Chandler does not mention that the battle was part of the War of 1812, fought between the United States and the British Empire. While most students are told that the war was caused by British impressment of American sailors into the British navy, or because the British would seize any ship bound for their enemy, France, if they did not first go to a British port and paying a tax (the Orders in Council), little is said about the prime grievance of those in what was then called “the West.”

Settlers on the frontier were incensed that the British had supported the Grand Indian Confederacy of Tecumseh with firearms and other support. Tecumseh had tried to get his fellow Native Americans to join together and fight westward expansion, but most Indian tribes rejected his efforts. The Cherokee, led by the Ridge, a great orator, essentially told Tecumseh to get lost, as they had no reason to fight the U.S. government.

Other tribes were divided over Tecumseh’s proposal. The Muscogee Confederation (called the Creek) was split between the Upper Creek who favored the plan, and the Lower Creek who vehemently opposed it. Upper Creek warriors, known as the Red Sticks, took up arms against the United States.

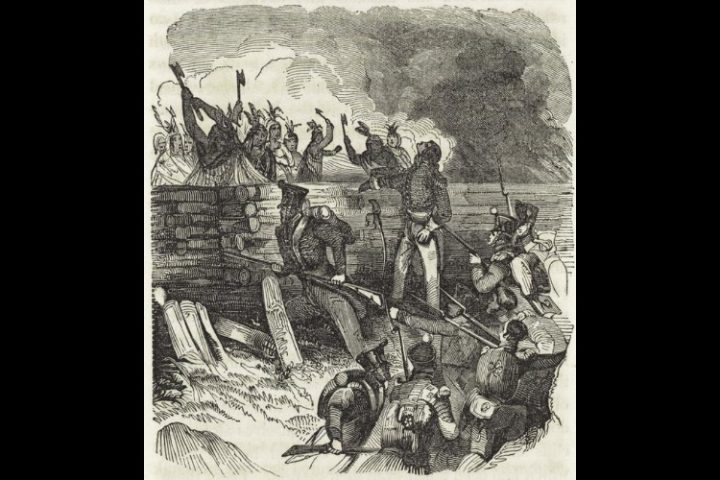

In August of 1813, some of these Red Stick warriors attacked Fort Mims, about 35 miles north of Mobile, Alabama. Led by William Weatherford and Peter McQueen, the Red Sticks overwhelmed the militia garrison at the fort, then proceeded to slaughter the civilian inhabitants who had taken refuge in the fort. Babies were killed by swinging them by their feet and smashing their heads into the stockade fence.

Those who escaped repeated the stories of the atrocities, and the countryside was aflame, demanding retaliation.

At Horseshoe Bend, they got it. Andrew Jackson was in command of a military force that included militia from Tennessee and elsewhere, along with Indians — including Lower Creeks and Cherokees. Several individuals who would later become prominent in history were at the battle, such as Sam Houston (who was severely wounded). The Ridge got his new name — Major Ridge — for his leadership of a Cherokee regiment that included future Cherokee chief, John Ross.

Without the help of the Cherokee and the Lower Creek, it is debatable whether Jackson would have won the battle. Yet, Chandler neglected to even mention them in her biased article. The Cherokee, under General John Coffee, used a wide flanking maneuver and crossed the Tallapoosa River, and turned the tide of the battle.

None of the above is written about by Chandler.

Chandler does quote RaeLynn Butler, the secretary for culture and humanities of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, who said, “When you hear the language and you hear the songs, it’s a feeling that is just overwhelming. Painful. Even though it’s hard to be here, it’s important that we share this history.”

I agree, Secretary Butler, it is important that we share this history — all of it.

The lessons to be learned from this event and its reporting by the Associated Press include that we should be cautious in accepting the reporting of the AP on historical events. As George Orwell wrote, “Those who control the past, control the future. Those who control the present, control the past.” Far too often, those with a left-wing agenda control the present, and thus control the past, seeking to control our future.

This skepticism should include not only history from the 19th century, retold by AP in a biased fashion to advance some political cause of today, but also recent history. Distortions of recent history are also used by progressives to construct a false narrative.

Certainly, the actions of President Andrew Jackson and the U.S. government in their dealings with tribal peoples is fair game for criticism. But in the case of the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, that “force” under Jackson’s command included Native Americans — their story deserves to treated fairly, as well.