Donald Sterling, Los Angeles Clippers owner, was recorded by his mistress making some crude racist remarks. Since then, Sterling’s racist comments have dominated the news, from talk radio to late-night shows. A few politicians have weighed in, with President Barack Obama congratulating the NBA for its sanctions against Sterling. There’s little defense for Sterling, save his constitutional right to make racist remarks. But in a sea of self-righteous indignation, I think we’re missing the most valuable lesson that we can learn from this affair — a lesson that’s particularly important for black Americans.

Though Sterling might be a racist, there’s an important “so what?” Does he act in ways commonly attributed to racists? Let’s look at his employment policy. This season, Sterling paid his top three players salaries totaling over $46 million. His 20-person roster payroll totaled over $73 million. Here are a couple of questions for you: What race are the players whom racist Sterling paid the highest salaries? What race dominated the 20-man roster? The fact of business is that Sterling’s highest-paid players are black, and 85 percent of Clippers players are black. Down through the years, hundreds of U.S. corporations have faced charges of racism, and many have been subjects of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission investigations, but none of them had such a favorable employment and wage policy as Sterling. How does one explain this? People with limited thinking ability might conclude that Sterling is a racist in his private life but a nice card-carrying liberal in his public life, manifested by his hiring so many blacks, not to mention paying Doc Rivers, the Clippers’ black head coach, a healthy $7 million a year. The likelier explanation is given no attention at all.

Let’s use a bit of simple economics to analyze the contrast in Sterling’s private and public behavior. First, professional basketball is featured by considerable market competition. There’s an open opportunity in the acquisition of basketball playing skills. Youngsters just buy a basketball and shoot hoops. There’s open competition in joining both high-school and college teams. You just sign up for tryouts in high school and get noticed by college scouts. Then there’s considerable competition among the NBA teams in the acquisition of the best college players. Minorities and less preferred people always do better when there are open markets instead of regulated markets.

Recently deceased Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker pointed this phenomenon out some years ago in his path-breaking study The Economics of Discrimination. Many people think that it takes government to eliminate racial discrimination, but economic theory predicts the opposite. Market competition imposes inescapable profit penalties on for-profit enterprises when they make employment decisions on any basis other than worker productivity. Professor Becker’s study of racial discrimination upended the view that discriminatory bias benefits those who discriminate. He demonstrated that racial discrimination is less likely in the most competitive industries, which need to hire the best workers.

According to Forbes magazine, the Los Angeles Clippers would sell for $575 million. Ask yourself what the Clippers would sell for if Sterling were a racist in his public life and hired only white players. All the evidence suggests that would be a grossly losing proposition on at least two counts. Percentage-wise, blacks more so than whites excel in basketball. That’s not to say that it is impossible to recruit a team of first-rate, excellent white players. However, because there is a smaller number of top-tier white players relative to black players, the recruitment costs would be prohibitive. In other words, a team of excellent white players would be far costlier to field than a team of excellent black players. It’s simply a matter of supply and demand.

The takeaway from the Sterling affair is that we should mount not a moral crusade but an economic liberty crusade. In other words, eliminate union restrictions, wage controls, occupational and business licensure, and other anti-free market restrictions. Make opportunity depend on one’s productivity.

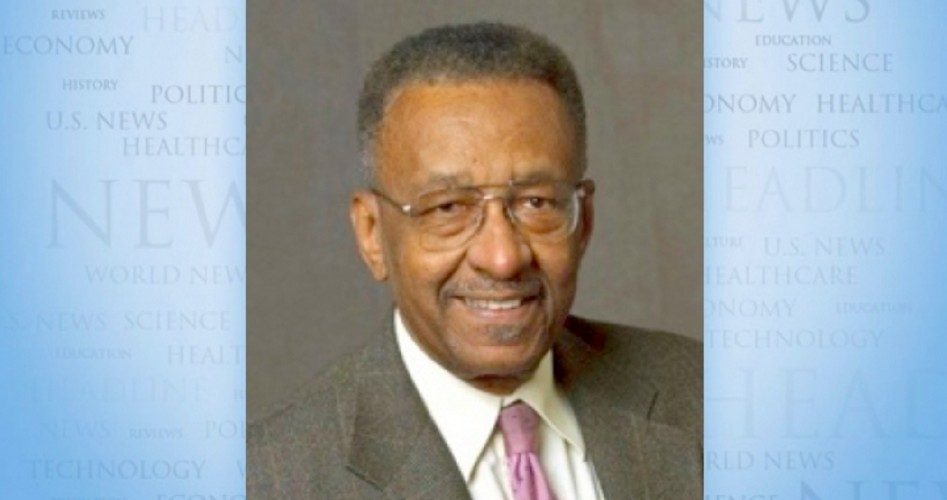

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM