Olympic hammer thrower Gwen Berry recently re-opened the debate on “The Star Spangled Banner” — our official national anthem since 1931, and our unofficial national anthem for decades prior to that — by disrespectfully turning her back on its playing during the Olympic trials in Oregon. She even covered her head with a T-shirt as the song was played.

Berry calls the song racist, while protesting that she does not hate America. “If you know your history,” Berry told the Black News Channel, “you know the full song of the National Anthem, the third paragraph speaks to slaves in America, our blood being slain … all over the floor. It’s disrespectful and it does not speak for black Americans. It’s obvious. There’s no question.”

Actually, there is a question, and what is obvious is that Berry, like so many Americans who have been brainwashed in far too many of America’s public and often, private, schools, in recent years, sees our country as inherently, structurally, and historically racist.

One wonders — if this country is so horribly bigoted — then why have millions of people from all over the globe immigrated to it since colonial times?

Berry’s argument is based on two lines from the third stanza of the song, which has the words, “No refuge could save the hireling and slave, From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.”

Nothing there about blood being slain (perhaps she meant shed, as blood isn’t slain) all over the floor, but it does mention “the hireling and slave.” What was that all about?

Berry is not the first person to assert that the third stanza of the “Star Spangled Banner” is intended as a slur against black slaves. Back in 2016, when NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick began his campaign to disrespect the American flag and the playing of the National Anthem before an NFL game, Shaun King of the New York Daily News wrote, “As it turns out, Key’s full poem actually has a third stanza which few of us have ever heard.” King then charged that the third stanza “openly celebrates” the killing of slaves.

In fact, Shaun King insisted that Key’s stirring tune “was rooted in the celebration of slavery and the murder of Africans in America.”

This is blatantly false.

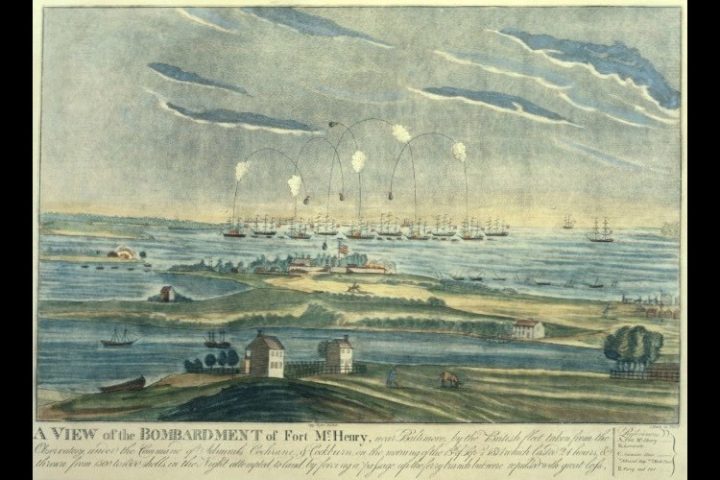

The song certainly does not “celebrate” slavery or the murder of slaves. According to King, black men, called the Corps of Colonial Marines, were serving the British military, and “Key despised them. He was glad to see them experience terror and death in war — to the point that he wrote a poem about it.” There’s little doubt that Key did not like anyone who was involved in the attack upon Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, which was what actually inspired the writing of the poem, later put to music and turned into a song. One might also recall — which Berry, Kaepernick, and King do not bother to mention or are just ignorant of — that Americans have never been too fond of the German mercenaries, the Hessians, whom King George III hired to suppress the American War for Independence.

Attempting to invade a country, whether one is British, German, or African, is not a way to win the love of that country.

And killing invading soldiers is not generally regarded as murder. What does King think the African mercenaries were going to do the defenders of Fort McHenry, given the chance?

Yes, it was the successful defense of Fort McHenry — not some abstract celebration of slavery or hatred of black Africans — that inspired Key to write his poem. He had been dispatched by President James Madison to negotiate the release of a civilian prisoner on a British warship, but the attack upon the fort delayed the release until after the battle, which lasted most of the night of September 13-14, 1814. When the first rays of sunshine lit up the “star-spangled” flag above Fort McHenry the next morning, Key took out an envelope he had with him and began to pen on it the words of his poem. It is ridiculous to the extreme for anyone to contend that Key wrote the poem even thinking about slavery, much less that it was somehow “rooted in the celebration of slavery.”

The poem was soon put to music, and, in the burst of patriotic fervor following the War of 1812, became a popular and beloved American tune. It grew in popularity over the course of the next several decades, being performed at Independence Day celebrations, and the U.S. Navy adopted it for official use in 1889. It was played at the 1918 World Series, and was so well-received that, by World War II, was being performed before every baseball game.

By then, Congress had responded to a national campaign by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and made it the National Anthem of the United States. Five million people signed the VFW petition, and with the signature of President Herbert Hoover, the “Star Spangled Banner,” which had been our unofficial national anthem, was made official.

That is some history that Berry, Kaepernick, King, and other leftists need to know.