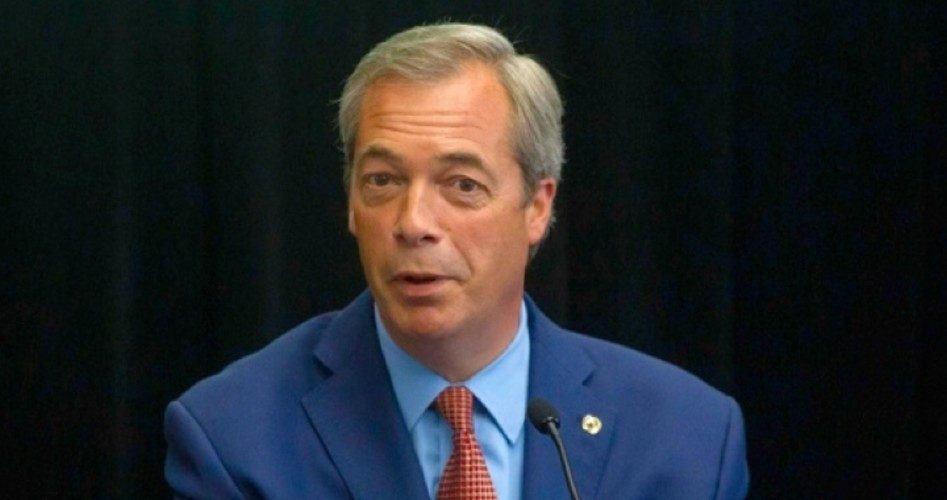

Nigel Farage (shown) resigned Monday from his position as leader of the UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party). His resignation statement, posted on the UKIP website, said:

I have decided to step aside as Leader of UKIP. The victory for the “Leave” side in the referendum means that my political ambition has been achieved. I came into this struggle from business because I wanted us to be a self-governing nation, not to become a career politician.

In a news conference, Farage promised to support the UKIP and its new leader. He added that his involvement in politics has come at a cost to himself and those around him. He referred to his numerous statements during the Brexit referendum campaign that he wanted his country back, and that he now wants his life back.

Farage also added: “I now feel that I’ve done my bit. I couldn’t possibly achieve more than we managed to get in that referendum.”

History doesn’t support Farage’s assertion that he couldn’t possibly achieve more than what was accomplished in the vote. Britain is still in the EU, and votes — as significant as they have been in the past — frequently haven’t accomplished the ends that were intended. They have defined the issue and who’s on each side, but when the opposition didn’t go quietly into the night, it’s obvious the battle has only begun.

Though the Declaration of Independence was passed in a unanimous vote by the colonies in the Continental Congress, King George III didn’t go quietly away. The final military engagement of that war was the Battle of Yorktown on October 19, 1781, over five years later. And the Treaty of Paris, where Britain recognized the independence of these United States, wasn’t drafted until November 30, 1782, and wasn’t signed until September 3, 1783.

President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill that would have renewed the charter of The Bank of the United States July 10, 1832. Nicholas Biddle, who was president of the bank, didn’t go quietly either. He fought back for many years. Even after the bank’s charter expired in 1836, it struggled to survive as a state-chartered bank. Biddle finally resigned as president of the bank in March of 1839. Robert Remini, in his book Andrew Jackson and the Bank War, cites the end of the bank, saying “With credit and reputation gone, the bank closed its doors in 1841, dragging down a number of other banks across the country.”

Hopefully, Nigel Farage’s resignation will be similar to that of General George Washington, who wanted to return to civilian life after the American War for Independence ended, only to find himself needed again to serve as a political leader to see the job done.

Photo of Nigel Farage: AP Images