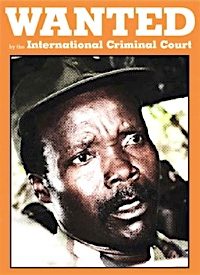

The Kony 2012 campaign is one of the latest causes that many Americans are supporting. A large number of Facebook subscribers are talking about the Ugandan warlord and international criminal Joseph Kony (left) — who abducted countless children from eastern and central Africa to become sex slaves and child soldiers — and calling for greater efforts to have him arrested. While the sudden show of support may be viewed as inspirational, some fear that the newfound attention being given to Uganda may compel international intervention, particularly by the United States.

For those who are unaware, the activism organization Invisible Children put out a documentary called Kony 2012 about the African guerrilla group leader, head of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), an organization that was supported by the public until it turned on its supporters to “purify” the Acholi people and transform Uganda into a theocracy. Kony was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court, but has been on the loose and unseen since 2006.

The documentary on Kony has gone viral recently — having been viewed by more than 32 million people in four days — sparking in a number of Americans the spirit of humanitarianism. They have been posting it on various social networking sites to show their support for capturing Kony. The campaign has the backing of many celebrities and politicians alike, including Lady Gaga, Bill Gates, George Clooney, Bill Clinton, Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, Harry Reid, and Angelina Jolie. And the list goes on. The documentary has been tweeted by a variety of celebrities including Justin Bieber, Rihanna, and Oprah Winfrey.

Polly Curtis and Tom McCarthy wrote of Kony 2012 in The Guardian:

With its slick Hollywood production values, the film has been an almost instant viral success, dominating Twitter worldwide and having one of the fastest ever take-offs on YouTube. The hashtag #stopkony has had hundreds of thousands of tweets, and millions of people now know something about Uganda and what is happening to children there. Support for the campaign to end the conflict in the country this year is spreading.

Even before the release of the documentary, the situation in Uganda did not entirely escape the attention of the U.S. government. In 2010, President Obama signed the LRA Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery bill passed by Congress in 2009 that sent American soldiers to Uganda to track down the LRA and capture Kony.

“Although the U.S. forces are combat-equipped, they will only be providing information, advice, and assistance to partner nation forces, and they will not themselves engage LRA forces unless necessary for self-defense,” Obama said at the time.

Predictably, the effort was painted as a humanitarian gesture, even as Uganda is a prized strategic asset. In 2005, investigative journalist Wayne Madsen reported on his website that the United States set up major communications and listening stations in Uganda.

The irony of the sudden support for stopping Kony in his tracks is that his appalling activities began in 1986, and therefore it took 26 years for interest suddenly to be stimulated. Furthermore, because Kony has not been seen or heard from for the last six years, some wonder if he is even still alive.

According to some analysts, the entire Kony 2012 campaign is “misrepresenting” the situation in Uganda in order to achieve a greater agenda.

“To call the campaign a misrepresentation is an understatement,” declared Ugandan blogger Angelo Izama, adding:

While it draws attention to the fact that Kony, indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court in 2005, is still on the loose, its portrayal of his alleged crimes in Northern Uganda are from a bygone era.

London’s Telegraph reported:

“What that video says is totally wrong, and it can cause us more problems than help us,” said Dr Beatrice Mpora, director of Kairos, a community health organisation in Gulu [Uganda], a town that was once the centre of the rebels’ activities.

“There has not been a single soul from the LRA here since 2006. Now we have peace, people are back in their homes, they are planting their fields, they are starting their businesses. That is what people should help us with.”

The Telegraph story also quotes Rosebell Kagumire, a Ugandan journalist specializing in peace and conflict reporting, who insisted, “This paints a picture of Uganda six or seven years ago, that is totally not how it is today. It’s highly irresponsible.”

According to the group Invisible Children, the purpose of the Kony 2012 campaign is to “support the international effort to arrest him, disarm the LRA and bring the child soldiers home.” In other words, military interventionism.

Some critics have raised concerns about Invisible Children’s endorsement of military action in Uganda to stop Kony. A counter-group called Visible Children, a Tumblr dedicated to evaluating the legitimacy of the Kony campaign, has raised several points about the Invisible Children organization:

The group [behind Kony 2012] is in favour of direct military intervention, and their money supports the Ugandan government’s army and various other military forces. Here’s a photo of the founders of Invisible Children posing with weapons and personnel of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Both the Ugandan army and Sudan People’s Liberation Army are riddled with accusations of rape and looting, but Invisible Children defends them, arguing that the Ugandan army is ‘better equipped than that of any of the other affected countries.’… These books [Abducted and Abused: Renewed Conflict in Northern Uganda and The Resolution of African Conflicts] each refer to the rape and sexual assault that are perennial issues with the UPDF [Uganda People’s Defense Force], the military group Invisible Children is defending.

Huffington Post blogger Michael Deibert makes the same argument, that Invisible Children advocates U.S. military support for the government of Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni, whose regime has been accused of human rights violations (ironically including the use of child soldiers) as well as election fraud.

Deibert concludes:

By blindly supporting Uganda’s current government and its military adventures beyond its borders, as Invisible Children suggests that people do, Invisible Children is in fact guaranteeing that there will be more violence, not less, in Central Africa.

I have seen the well-meaning foreigners do plenty of damage before, so that is why people understanding the context and the history of the region is important before they blunder blindly forward to “help” a people they don’t understand.

US president Bill Clinton professed that he was “helping” in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1990s and his help ended up with over 6 million people losing their lives.

Writer Jeff Sparrow of Drum TV points to warlordism in Afghanistan to assert that “military interventions, no matter how benevolent their rhetoric, tend to foster warlordism rather than ending it. The ongoing violence in Afghanistan means that the nation’s more subject to the rule of the gun, not less.”

In addition to these concerns, Visible Children has also investigated the finances of the group behind the Kony 2012 campaign, Invisible Children. It discovered:

Invisible Children has been condemned time and time again. As a registered not-for-profit, its finances are public. Last year, the organization spent $8,676,614. Only 32% went to direct services (page 6), with much of the rest going to staff salaries, travel and transport, and film production. This is far from ideal, and Charity Navigator rates their accountability 2/4 stars because they haven’t had their finances externally audited. But it goes way deeper than that.

Likewise, Reddit users have observed that Invisible Children has failed to comply with the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance. “While participation in the Alliance’s charity review efforts is voluntary, the Alliance believes that failure to participate may demonstrate a lack of commitment to transparency,” states Reddit’s evaluation.

Others contend that the campaign successfully inspires emotional support, but fails to provide a real solution that can be accomplished by individuals. According to Yahoo News, “Others across the Twittersphere have accused Kony 2012 of promoting slacktivism — the idea that sharing, liking, or retweeting will solve a problem — across the social web.”

TMS Ruge, the Ugandan co-founder of the development NGO Project Diaspora, which seeks to “mobilize the African diaspora to invest in Africa,” believes the Kony campaign draws attention away from more pressing issues:

Catching and stopping Kony is not a priority of immediate concern. You know what is? Finding a bed net so that millions of kids don’t die every day from malaria. How many of you know that more Ugandans died in road accidents last year (2,838) than have died in the past three years from LRA attacks in [the] whole of central Africa (2,400)?