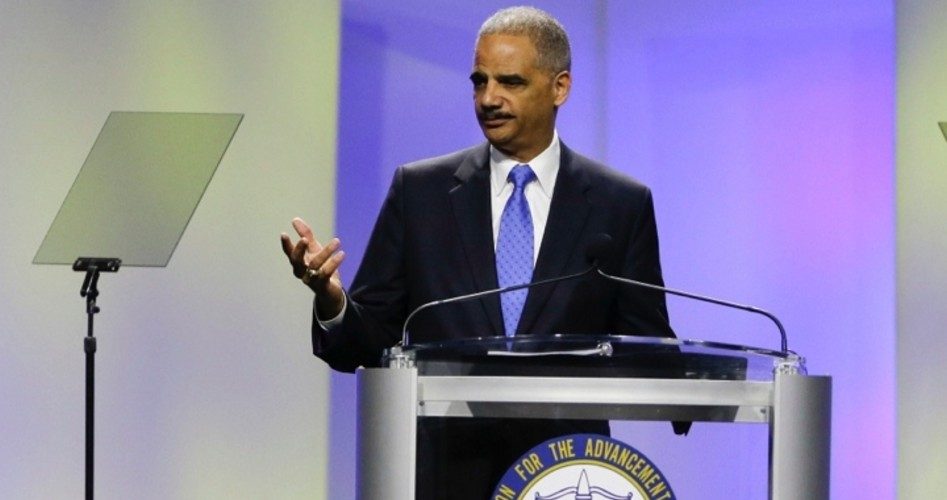

When Attorney General Eric Holder (shown) told his audience at the NAACP’s annual convention on Tuesday, “It’s time to question laws that senselessly expand the concept of self-defense and sow dangerous conflict in our neighborhoods,” he was either ignorant of, or didn’t want to consider, the precedents the Supreme Court has used for nearly 100 years to defend the “stand your ground” laws to which he was referring. Twenty-five states have adopted some form of those laws, including the State of Florida. Simply stated, those laws provide that an individual may be justified in using deadly force to defend himself against an unlawful threat without an obligation to retreat first.

In the Zimmerman case just concluded, Florida’s “stand your ground” law was never considered, as Zimmerman had no option of retreat. But Holder used that case nevertheless to open a discussion that has been largely closed for decades.

Back in 2000, Second Amendment scholar and Research Director of the Independence Institute David Kopel published his analysis of a dozen self-defense cases brought before the Supreme Court in the 1890s. These cases laid the legal groundwork for a decision in 1921 that “became the most important armed self-defense case in American legal history, upholding and extending the right to armed self-defense,” according to Kopel. Calling them “The Self-Defense Cases,” Kopel examined each of them in turn, including the primary case — Beard v. United States — which led inevitably and directly to the 1921 decision, Brown v. United States, that has served as the touchstone that Holder now wants to “question.”

The opinion in the 1895 Beard case was succinct:

A man assailed on his own grounds, without provocation, by a person armed with a deadly weapon and apparently seeking his life is not obliged to retreat, but may stand his ground and defend himself with such means as are within his control; and so long as there is no intent on his part to kill his antagonist, and no purpose of doing anything beyond what is necessary to save his own life, is not guilty of murder or manslaughter if death results to his antagonist from a blow given him under such circumstances. [Emphasis added.]

In the above mentioned case, three brothers went to a farm belonging to one Mr. Beard seeking to retrieve a cow that he possessed. He drove them away but they returned later and attacked Beard, who struck one of the brothers on the head with his shotgun, inflicting a fatal injury. The opinion made it clear that Beard was not obligated to retreat:

The defendant was where he had the right to be, when the deceased advanced upon him in a threatening manner and with a deadly weapon, and if the accused did not provoke the assault, and had at the time reasonable grounds to believe, and in good faith believed, that the deceased intended to take his life, or do him great bodily harm, he was not obliged to retreat nor to consider whether he could safely retreat, but was entitled to stand his ground and meet any attack made upon him with a deadly weapon in such way and with such force as, under all the circumstances, he at the moment, honestly believed, and had reasonable grounds to believe, were necessary to save his own life or to protect himself from great bodily injury. [Emphasis added.]

In 1921 the Supreme Court had an opportunity to consider the Brown case in which a man named Hermes, who had twice assaulted Brown with a knife and warned him that he would kill him in his third attempt, did in fact attack Brown. Brown ran to his coat where he kept a pistol, drew it on Hermes, and shot him dead. The decision was written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. who said:

The right of a man to stand his ground and defend himself when attacked with a deadly weapon, even to the extent of taking his assailant’s life, depends upon whether he reasonably believes that he is in immediate danger of death or grievous bodily harm from his assailant, and not upon the detached test whether a man of reasonable prudence, so situated, might not think it possible to fly with safety or to disable his assailant, rather than kill him.…

Many respectable writers agree that, if a man reasonably believes that he is in immediate danger of death or grievous bodily harm from his assailant, he may stand his ground, and that, if he kills him, he has not succeeded the bounds of lawful self-defense. That has been the decision of this Court [in] Beard v. United States.

Detached reflection cannot be demanded in the presence of an uplifted knife. [Emphasis added.]

As Kopel noted, the “detached reflection” comment from Holmes “has become part of American folk wisdom, further influencing the tendency of the American mind against retreat.”

Historian Richard Maxwell Brown, the author of No Duty to Retreat and professor of history at the University of Oregon, said that history is on the side of the “stand your ground” laws that Holder wants to question:

To Holmes — as to so many other Americans — the right to stand one’s ground and kill in self-defense was as great a civil liberty as, for example, freedom of speech.

It may not be possible to let Holder off the hook by suggesting that he doesn’t know his history or these legal precedents that have guided the court for 92 years. If he does know, then he can be charged with trying to delegitimize the law by questioning it. As Kopel so eloquently put it back in 2000:

The same moral imperative which is reflected in laws against murder requires that victims be able to use whatever force is necessary to defend themselves and their families from murder attempts. If the state ignores the moral imperative of self-defense, the state loses its moral authority.

Photo of Attorney General Eric Holder at NAACP convention in Orlando, Fla.: AP Images

A graduate of Cornell University and a former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American magazine and blogs frequently at www.LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].