Have you ever read The Federalist Papers?

Have you read Federalist No. 6, 18, or 20?

Do you remember a name being mentioned in each one of those essays: Abbe de Mably?

Did you ever stop and wonder who was this man that James Madison and Alexander Hamilton were quoting, or wonder why they quoted him at all?

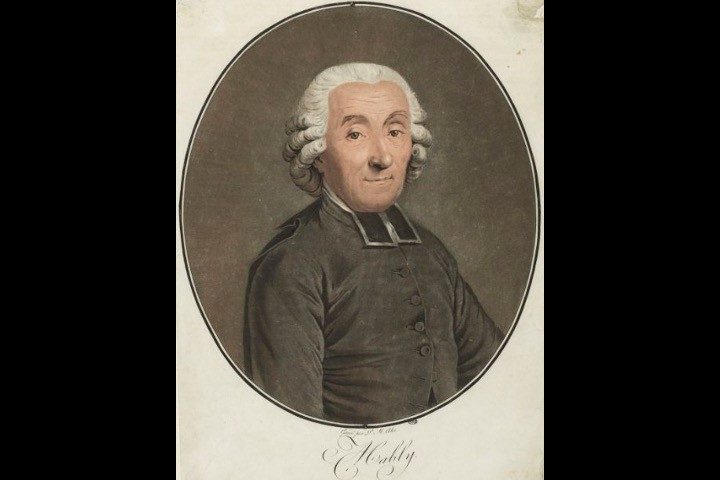

The Abbe Gabriel Mably — abbe is the French word for an abbot, a title for lower-ranking Catholic clergy in France — was born Gabriel Bonnot de Mably, in Grenoble, France, in 1709. He was a French philosopher, historian, and writer. He was very well acquainted with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and they influenced each other in their writings. Mably died in Paris in 1785.

Beyond Rousseau, Mably’s circle of friends and correspondents encompassed great thinkers on this side of the Atlantic, as well.

Benjamin Franklin and John Adams were personal friends and frequent correspondents of the Abbe de Mably, and both held the latter in high esteem and consulted him frequently on matters of political philosophy.

When you read the following selections from the writings of the Abbe de Mably, you will quickly comprehend why the bureaucrats who control the curriculum in American schools have completely removed any mention of Mably — his influence on the Founding Fathers and his political philosophy — from the American History books used by millions of American children today.

State Sovereignty, Nullification, and the Nature of the Union:

Much of what the abbe wrote supports the position that the states that formed the American union retained their independence and sovereignty in all but a few enumerated areas. Consider this observation taken from his essays published as Remarks Concerning the Government and Laws of the United States of America:

It is a great advantage for the Americans, that the thirteen States have not confounded together their rights, their independence and their freedom, for the purpose of forming but one republic, establishing the same laws, and acknowledging the same magistrates….

Whilst almost every European nation remains plunged in ignorance respecting the constitutive principles of society, and only regards the people who compose it as cattle upon a farm managed for the particular and exclusive benefit of the owner, we become at once astonished and instructed by the circumstance that your thirteen republics have, in the same moment, discovered the real dignity of man, and proceeded to draw from the sources of the most enlightened philosophy those humane principles on which they mean to build their forms of government….

One of the most dangerous rocks which hangs over the system of politics is an inclination to blend together and unite establishments, good in themselves, and when separately considered, but which cannot possibly assimilate….

Far from soliciting, like them, in every quarter, for a new master, your efforts were directed solely to the act of raising amongst yourselves a throne sacred to liberty. In all your constitutions, you reascended to the principles of nature; you have established, as a certain axiom, that all political authority derives its origin from the people; and that in the people alone rests the unalienable right of either enacting, annulling, or modifying laws, in the moment when they perceive their error, or aspire to the enjoyment of some greater good….

Amidst this vast extent of country which you possess, how could it have been possible firmly to have established the empire of the laws; to have prevented the several springs of administration from becoming relaxed, in consequence of their distance from that centre to which they were indebted for their powers of motion; and, equally to have cast the same vigilant eye through every quarter, for the purpose of either hindering abuses, or forcing them to disappear? Unavoidably must you have perceived a relaxation of manly firmness; a degradation of morals; a love of liberty giving ground to licentiousness; and soon would you have degenerated into a republic, either languishing through all its frame, or agitated by seditions, which must totally have dismembered it.

The contrary measure which the colonists have adopted, by forming a federal republic, each preserving its independence, may impart to laws the whole of that force which is so necessary to secure for them an inviolable respect….

One of the most dangerous rocks which hangs over the system of politics is an inclination to blend together and unite establishments, good in themselves, and when separately considered, but which cannot possibly assimilate.

Dangers of Democracy:

It is not possible for the people to suppose themselves free without experiencing an inclination to abuse their liberty, because the nature of their passions continually stimulates their endeavours to live more at ease. The hopes which they indulge prepare their minds for greater indocility; they cannot avoid envying the lot of their superiors, and, consequently, they become anxious either to exalt themselves into equal eminence, or to reduce those citizens who are above them to a level with themselves….

The occurrences which have constantly taken place, amidst all nations, where the liberty of the citizens was not established and fostered with a degree of prudence equal to that recorded to have prevailed at Lacedæmon, ought to serve as a lesson to legislators not to employ democracy in a republic, but with extreme precaution….

But, if the legislative power, which is the soul of the state, or rather the pivot whereon turns the whole political machine, be not established according to the most just proportions, what disorders will not result from this extreme defect!…

That system of politics which ought, amidst its present arrangements, to secure provisions for the future, will run into the violence of error, by endeavouring to establish, amongst the citizens, an equality of rights and privileges….

[T]o say nothing of these adventurers who, soaring out of their private authority, may exalt themselves into the stations of tribunes of the people, who can answer for it that no rich trader, no merchant of great opulence will, by affecting to pursue a popular line of politics, avail himself of the disquiet, the hatred and the jealousy which constantly spring up in a democracy where fortunes are so disproportionate, to add fuel to the fire of civil discord, to make a trial of his own power, and to establish his own tyranny.

From state sovereignty to nullification to the dangers of democracy to the evil of tyranny, these selections from the writings of Gabriel Bonnot, the abbe de Mably, should be sufficient to prove why American children will never read his name in the textbooks purporting to teach them the history of the United States.