Some of the confusion in thinking about matters of race stems from the ambiguity in the terms that we use. I am going to take a stab at suggesting operational definitions for a couple terms in our discussion of race. Good analytical thinking requires that we do not confuse one behavioral phenomenon with another.

Let’s start with “discrimination.” Discrimination is the act of choice, and choice is a necessary fact of life. Our lives are spent discriminating for or against different activities and people. Some people shop at Wegmans and thus discriminate against Food Giant. Some students discriminate against George Mason University in favor of attending Temple University. Many people racially discriminate by marrying within their own race rather than seeking partners of other races. People discriminate in many ways in forming contracts and other interrelationships. In each case, one person is benefitted by discrimination and another is harmed or has reduced opportunities.

What about prejudice? Prejudice is a useful term that is often misused. Its Latin root is praejudicium, meaning “an opinion or judgment formed … without due examination.” Thus, we might define a prejudicial act as one where a decision is made on the basis of incomplete information. The decision-maker might use stereotypes as a substitute for more complete information.

We find that in a world of costly information, people seek to economize on information costs. Here is a simple yet intuitively appealing example. You are headed off to work. When you open your front door and step out, you are greeted by a full-grown tiger. The uninteresting prediction is that the average person would endeavor to leave the area in great dispatch. Why he would do so is more interesting. It is unlikely that the person’s fear and decision to seek safety is based on any detailed information held about that particular tiger. More likely, his decision to seek safety is based on tiger folklore, what he has been told about tigers or how he has seen other tigers behave. He prejudges that tiger. He makes his decision based on incomplete information. He uses tiger stereotypes.

If a person did not prejudge that tiger, then he would endeavor to seek more information prior to his decision to run. He might attempt to pet the tiger, talk to him and seek safety only if the tiger responded in a menacing fashion. The average person probably would not choose that strategy. He would surmise that the expected cost of getting more information about the tiger is greater than the expected benefit. He would probably conclude, “All I need to know is he’s a tiger, and he’s probably like the rest of them.” By observing this person’s behavior, there’s no way one can say unambiguously whether the person likes or dislikes tigers.

Similarly, the cheaply observed fact that an individual is short, an amputee, black, or a woman provides what some people deem sufficient information for decision-making or predicting the presence of some other attribute that’s more costly to observe. For example, if asked to identify individuals with doctorate degrees in physics only by observing race and sex, most of us would assign a higher probability that white or Asian men would have such degrees than black men or women. Suppose you are a police chief and you’re trying to find the culprits breaking into cars, would you spend any of your resources investigating people in senior citizen homes? Using an observable attribute as a proxy for an unobservable or costly-to-observe attribute lies at the heart of decision theory.

Lastly, is there a moral dimension to discrimination and prejudice? Should one be indifferent about whether he attends Temple University or George Mason University and thus makes his decision by flipping a coin? Is it more righteous to use the same technique when choosing to marry within or outside his race? Is it morally superior to be indifferent with respect to race in marriage, employment and socializing? Can one make a rigorous moral case for government coercion to determine whether one attends Temple University or George Mason University, marries outside of his race, or is indifferent about the racial characteristics of whom he employs?

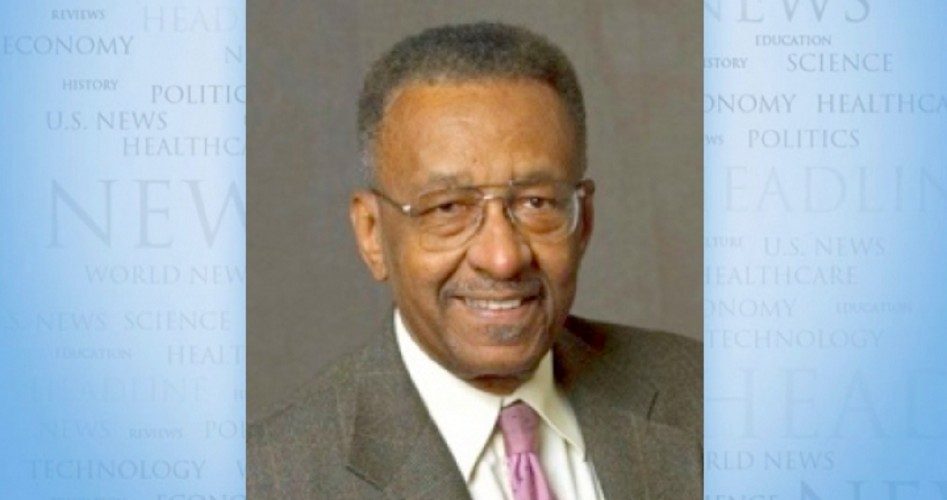

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate webpage at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2020 CREATORS.COM