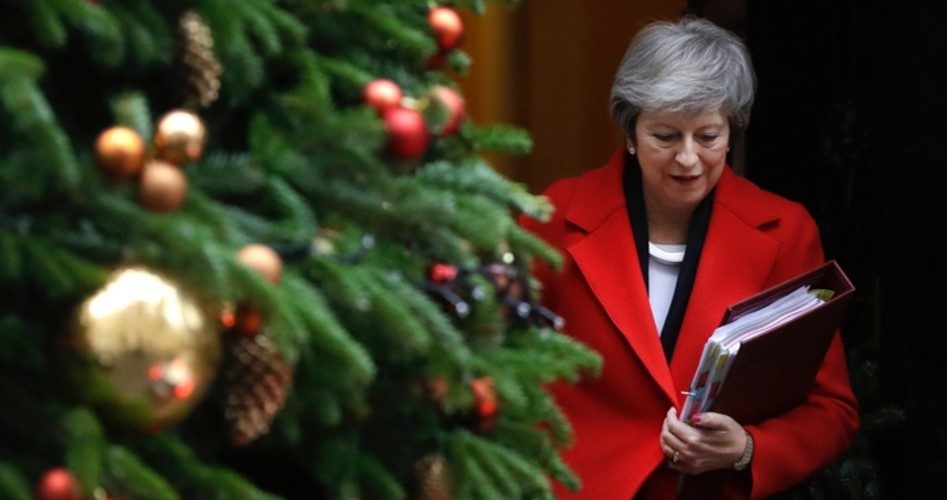

It was a tough Tuesday for U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May as the House of Commons handed her three significant defeats in the space of one hour. All three votes were connected to the Brexit issue, which is coming to a head in Great Britain as the March 31, 2019 exit date looms.

In 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Since then, May has been tasked with coming up with a deal in which the United Kingdom can leave the union while remaining on good terms with Europe.

May’s compromise deal, called a “soft Brexit” by detractors, is in peril. She issued a fiery defense of the deal in advance of the votes, warning that “Brexit could be stopped entirely” should the deal be voted down next Tuesday when it is scheduled to be voted on by Parliament.

While May recognized the criticisms of the current deal, she argued against scrapping it. “We should not let the search for a perfect Brexit prevent a good Brexit that delivers for the British people.”

“And we should not contemplate a course that fails to respect the result of the referendum, because it would decimate the trust of millions of people in our politics for a generation.”

One of the votes held May’s government in contempt of Parliament for refusing to publish the legal advice it ordered in connection with the “Irish Backstop” issue. The Parliament then voted again to publish the text of the legal advice. Attorney General Geoffrey Cox was even facing the prospect of being suspended from Parliament over his refusal to publish the advice.

Succinctly put, the Irish Backstop issue is meant to make certain that the border between the independent Republic of Ireland and U.K.-controlled Northern Ireland remain open regardless of the United Kingdom’s future relationship with the European Union.

These votes prompted the government to reluctantly publish the advice, a portion of which argues that, because of the Irish Backstop issue, the U.K. could be linked long-term to the EU in an unofficial trade union and still be subject to many EU laws.

From the legal advice: “While it will not be directly bound by EU rules, GB [Great Britain] will be obliged to observe a range of regulatory regulations in certain areas, such as environmental, labour, social and competition laws (the “level playing field”), which reflects varying levels of correspondence to EU standards.”

The third vote, which is potentially the most damaging for May, was an amendment brought forth by Tory Brexit opponent Dominic Grieve, which lays out what might happen should May’s deal be rejected next week. That amendment specifies that, should May’s deal not be accepted, the government would have to come back to the House of Commons within three weeks to discuss what course will next be taken. This will give members of Parliament (MPs) a significant say in how the U.K. would precede on Brexit.

Among the likely options MPs would consider, should the Grieve amendment be triggered, might be that Great Britain would stay in a permanent customs union with the EU, engage in a membership agreement in the single EU market or decide on a new referendum where voters would again decide whether to leave the EU — a “do over” of the original Brexit vote.

26 Tory MPs abandoned May and voted for the Grieve amendment, a sure sign of May’s weakened influence in her own party.

In other Brexit related news, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled that, under Article 50 of the EU treaty, the government of Great Britain has the right to unilaterally decide, against the wishes of its citizens, to cancel the decision to leave the EU, up until the time when a formal agreement is reached.

The statement from the ECJ, which is non-binding, declared that “Article 50 allows the unilateral revocation of the notification of the intention to withdraw from the EU.”

It’s an ugly, complicated mess. Should no agreement be reached — which seems likely at this point — it could mean that Great Britain might remain in the EU, against the wishes of its own people. Another possibility is Great Britain could leave the EU with no deal, which could lead to economic chaos, not just in Europe but worldwide. The EU might also establish a border between the Republic of Ireland, an EU member, and Northern Ireland, which is a part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. And neither Ireland nor Northern Ireland wants such a border.

PM May might have been in a no-win situation from the start. Both sides of the argument seem dug in, with compromise appearing impossible. The only way to avoid this kind of international entanglement is to not engage in multi-national agreements such as the EU in the first place.