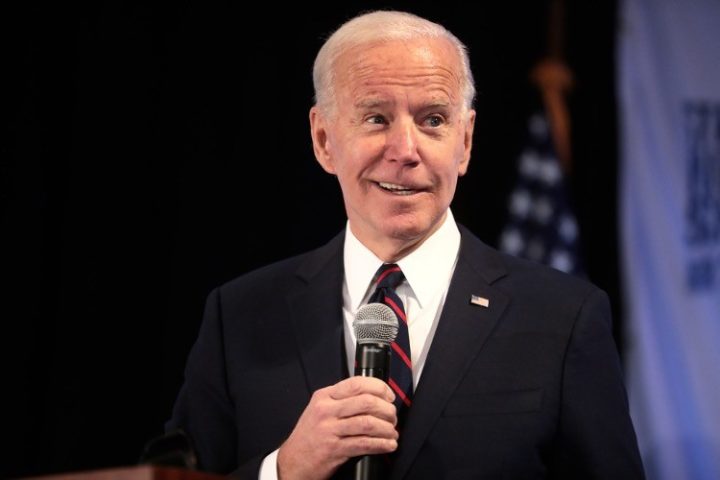

On March 11, 2022, President Biden said, “The idea that we’re going to send in tanks to Ukraine, that’s called World War III.”

Last Wednesday, Biden announced the plan to send 31 U.S. M1 Abrams tanks to Ukraine for use in that country’s war with Russia.

So, is this Biden’s declaration of war?

Likely not, but his assumption to bypass Congress and to accelerate the war in Ukraine and the U.S. contribution to that conflict is unquestionably unconstitutional and is an act of autocracy that should be opposed by every American who considers himself a friend of the U.S. Constitution and the very limited federal government created by the states in that document.

Biden explained that his decision to send tanks to Ukraine was in support of “Ukraine’s ability to fight off Russian aggression to defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity is a worldwide commitment.”

If only the president held state sovereignty and territorial integrity in such high regard and would commit himself to fight off federal aggression!

Now, the only way to know if the president of the United States possesses the power to unilaterally walk “in lockstep with our Allies” is to read the roster of powers granted by the states in Article II of the U.S. Constitution.

You may — and should — look for yourself, but I can assure you that sending military equipment overseas to foreign governments to wage war is NOT something the head of the executive branch is authorized to do.

In fact, the man dubbed by history as the Father of the Constitution — James Madison — wrote extensively about how the president is the last person any free people would agree to see endowed with power over the sword of state.

Within five years of the publishing of The Federalist Papers (and four years of the ratification by the states of the Constitution), the co-authors of those seminal and influential essays on American political theory and constitutional interpretation were back at their desks once again writing letters to the editors of newspapers.

This time, however, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton weren’t allies working to persuade others to commit to their common constitutional cause, but they were opponents, striving through their letters to reveal each other’s perceived constitutional misdeeds to the American people.

This episode in American history is known as the “Pacificus-Helvidius” debates, named for the pen names adopted by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, respectively.

In the earliest days of the Republic, the precise balance of powers between the legislative and executive branches in the arena of foreign affairs was unsettled. The Constitution, many argued, wasn’t clear on the point and the various views on the matter created controversy.

George Washington issued the Neutrality Proclamation of 1793 after France declared war on Holland and Great Britain. According to Washington’s way of thinking, it was in the best interest of the country to avoid war at all costs and he did not want the belligerents to be unsure of the official American position.

While certainly laudable, some of Washington’s colleagues considered the Neutrality Proclamation to be hostile to the French, as it required the U.S. government to violate a provision of the Treaty of Alliance signed by France and the United States in 1778. Thomas Jefferson was among the most vociferous of the claque calling out Washington for allegedly violating the prior agreement.

Some of the opposition, including Jefferson and Madison, believed that the advice and consent of the Senate should have been sought before President Washington issued any declaration of the official American position on any topic touching upon foreign affairs.

Alexander Hamilton was one of the first president’s most ardent advocates, however. And that’s where the trouble started.

Just weeks after the Neutrality Proclamation was published, Hamilton wrote a letter defending the document. Then, beginning in June 1793, he wrote an essay almost once a week, under the pen name Pacificus, in support of President Washington, his administration, and his policies.

After the seventh “Pacificus” letter was published on July 27, 1793, Jefferson wrote a now-famous letter to Madison, pleading, “my dear sir, take up your pen.”

Madison took up his pen, and on the 24th of August, 1793, he responded to Hamilton’s “Pacificus” essays, using the pseudonym “Helvidius.”

In the first letter, Madison writes that the first Pacificus essay “may prove a snare to patriotism” and warns that he (Hamilton) has advocated principles “which strike at the vitals of its constitution.”

Later in the essay, Madison recommends that in all questions concerning the correct conduct of federal officials, Americans must be guided by “our own reason and our own constitution.”

And, in a statement that is as timely now (perhaps more so) than it was then, Madison writes that the power to declare war is “of a legislative and not an executive nature.”

He continues on that subject:

Those who are to conduct a war [the Executive Branch] cannot in the nature of things, be proper or safe judges, whether a war ought to be commenced, continued, or concluded. They are barred from the latter functions by a great principle in free government, analogous to that which separates the sword from the purse, or the power of executing from the power of enacting laws.

Madison is so strident in his insistence that the power to make war not be placed in the presidency, that his next letter (Helvidius Number 2) begins with the bold pronouncement that if any president were to presume the war-making power, “no ramparts in the constitution could defend the public liberty or scarcely the forms of republican government.”

In the modern era, and most relevantly in the case of Joe Biden’s provision of tanks to Ukraine, the Congress was not involved in that decision.

On that subject, Mr. Madison once again makes a clear and constitutionally sound statement that, if applied today, would save the United States billions of dollars and thousands of lives in the prosecution of scores of unconstitutional combat missions over the past few decades.

“Until war be duly authorized by the United States, they are actually neutral when other nations are at war, as they are at peace (if such a distinction in terms is to be kept up) when other nations are not at war,” Madison declared in Helvidius 2.

Finally, Madison explains in Helvidius 4 why Americans must remain vigilant, keeping close watch over the actions of their elected representatives. To equal degree, though, Americans must be familiar with the powers granted to those representatives lest they claim to possess constitutional powers, powers not enumerated in that document.

Finally, I’ll close with two quotations, one from Joe Biden and one on the same theme from John Quincy Adams:

First, this from Joe Biden on America’s role in restoring liberty to Ukraine:

These tanks are further evidence of our enduring and unflagging commitment to Ukraine and our confidence in the skill of the Ukrainian forces….

Ukrainians are fighting an age-old battle against aggression and domination. It’s a battle Americans have fought proudly time and again, and it’s a battle we’re going to make sure the Ukrainians are well equipped to fight as well.

This is about freedom. Freedom for Ukraine, freedom everywhere. It’s about the kind of world we want to live in and the world we want to leave our children.

So, may God protect the brave Ukrainian defenders of their country who keep the flame of liberty burning brightly as we can.

Now, pay close attention to the wise words of John Quincy Adams regarding America’s obligation to fight for the freedom of foreign countries:

America, with the same voice which spoke herself into existence as a nation, proclaimed to mankind the inextinguishable rights of human nature, and the only lawful foundations of government. America, in the assembly of nations, since her admission among them, has invariably, though often fruitlessly, held forth to them the hand of honest friendship, of equal freedom, of generous reciprocity.

She has uniformly spoken among them, though often to heedless and often to disdainful ears, the language of equal liberty, of equal justice, and of equal rights.

She has, in the lapse of nearly half a century, without a single exception, respected the independence of other nations while asserting and maintaining her own.

She has abstained from interference in the concerns of others, even when conflict has been for principles to which she clings, as to the last vital drop that visits the heart.

She has seen that probably for centuries to come, all the contests of that Aceldama the European world, will be contests of inveterate power, and emerging right.

Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be.

But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy.

She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all.

She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.

She will commend the general cause by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example.

She well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom.

The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force….

She might become the dictatress of the world. She would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit….