On the one hand, the British government has been talking lately about restoring some of its subjects’ lost civil liberties and privacy. On the other hand, it has just taken another step down the road to the total surveillance society: The Financial Services Authority, according to the New York Times, has instituted new rules requiring “all financial services firms … to record any relevant communication by employees on their work cellphones” and to discourage “employees from taking client orders or discussing and arranging transactions on their private cellphones, where conversations cannot be recorded.”

Britain thus becomes “the only country in Europe to explicitly require the taping of conversations on business cellphones,” writes the Times, with the rule affecting “about 16,000 cellphones issued by financial services firms, which will be required to keep the recorded conversations for six months.” The paper adds: “Some financial services firms voiced concern about the additional costs of recording cellphone conversations and the legality of recording conversations when bankers traveled abroad, the F.S.A. said. One unidentified investment bank estimated that the cost of recording all BlackBerry phones could reach 2.6 million [pounds, $4.2 million] each year, according to the F.S.A. policy statement.” Not surprisingly, the FSA, which already requires businesses to record land-line conversations and save emails at their own expense, was not swayed in the least by these concerns.

With the new rule, the British government is demanding that businesses make it easier for the government to pry into their internal affairs. Of course, as with all government invasions of privacy, this measure is being sold as an attempt to thwart criminals. Sarah Bailey, an FSA spokeswoman, told the Times, “We expect the rules to increase the volume and quality of information available to us to use as additional evidence in insider trading cases.”

This assumes, however, that insider trading should be criminalized in the first place. In fact, such laws enforce a kind of “information socialism,” as Ilana Mercer put it, whereby “those who are in a position to benefit from the risks and rewards of their occupation” are prohibited from doing so in favor of redistributing their intellectual property to the general public before they can act on the information they possess. Yet as Frostburg State University economics professor William L. Anderson averred: “Information that is worth anything in a market setting at all by definition must come from ‘the inside.’ There is no way to make information public in the way that the government wants it to be done without making all relevant information useless for the purpose of economic decision making.” (Emphasis in original.)

Anderson also pointed out that while the government prohibits private individuals from acting on the basis of “inside” information, it “does not consider it to be a breach of the law when its own officials act upon ‘inside’ information to protect themselves. For example, after receiving warnings [in the summer of 2001] that terrorists might hijack U.S. airliners, [then-]U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft began to fly on private aircraft. Some members of Congress grumbled, but no one was sent to Ashcroft’s office to place him in handcuffs and chains.”

Moreover, banning insider trading helps no one — except prosecutors, such as former U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani, who are looking to make a name for themselves — and harms many. By prohibiting those with knowledge from acting on it immediately, laws against insider trading ensure that those persons and their acquaintances do not profit from increased stock prices but do lose as much as outsiders when stock prices fall — a triumph of envy, certainly, but not of justice. Furthermore, were insiders permitted to act on their knowledge before it became public, their stock purchases or sales would signal to outsiders the direction in which the insiders expect the stock price to go, enabling outsiders to buy or sell earlier, increasing their profits or reducing their losses. Prohibiting insider trading merely ensures that insiders and outsiders alike earn lower profits and suffer greater losses.

Therefore, the British government is mandating easier access to businesses’ heretofore private information allegedly to crack down on an activity that should not even be illegal. It is only a matter of time before Her Majesty’s government finds other, even less benign uses for its newfound snooping powers — and before other governments, including the one in Washington, arrogate similar powers to themselves.

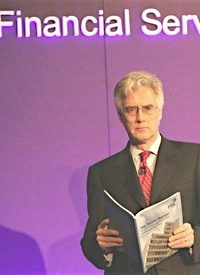

Photo: Lord Adair Turner, chairman of Britain’s Financial Services Authority: AP Images