The Duma (the lower house of Russia’s legislature) on July 9 passed a bill that will allow the Federal Security Service (FSB) to issue warnings to people "whose acts create the conditions for the committing of a crime," the Moscow News reported three days later.

The bill was opposed by all of Russia’s political parties except the pro-Kremlin United Russia, which has 315 seats in the 450-seat Duma. United Russia’s chairman is Vladimir Putin. The report said the measures were proposed by the government in the wake of the March 29 Metro bombings by Chechen separatists.

A Reuters report cited Kremlin critics who say the FSB, “formerly headed by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, could use its additional powers to target and intimidate opposition groups.” The report also noted: “The FSB was formed from the remains of the KGB, which was broken up in 1991 as the Soviet Union collapsed. Its influence grew greatly after Putin became president in 2000 and ordered it to lead the fight against Islamist rebels.”

A July 12 report from the Italian-based Asia News.it explored the possible effects of the new Russian law in detail, noting:

The bill states that no legal entity — including political parties — can organize a public meeting, if guilty of administrative violations. These range from excessive speed to traveling without a ticket on public transport. According to Maxim Rokhmistrov, deputy head of the Liberal Democratic Party, the bill is unconstitutional because "administrative offense cannot result in a person losing their right to free assembly."

In other words, merely having received a traffic ticket may be enough to bar you from political activism, under the new law.

The Moscow Times quoted Maxim Rokhmistrov, deputy head of the Liberal Democratic Party (which describes itself as a centrist, pro-reform democratic party), who called the bill unconstitutional because an administrative offense cannot result in a person losing their right to free assembly. “After paying the fine, a person convicted of an administrative offense cannot be further deprived of other rights,” said Rokhmistrov.

KyivPost, an English language newspaper based in the Ukraine, quoted Vladimir Ulas, a member of the opposition Communist Party, who said: "It’s a step toward a police state. It is effectively a ban on any real opposition activity." Considering FSB’s origins in the KGB of the communist-ruled Soviet Union, it is difficult to ascertain if Ulas’s statement was regarded with any degree of seriousness in Russia, or dismissed as sheer party-line propaganda.

KyivPost also quoted Gennady Gudkov, identifying him as a spokesman for the Fair Russia Party (also called "A Just Russia"), who described the new law as "a left-over order from the Soviet Union." Wikipedia identifies Gudkov as Chairman of the People’s Party of the Russian Federation, which joined Fair Russia in 2007. The online encyclopedia also notes that Gudkov worked for the KGB from 1982 to 1992.

It is difficult to determine if Gudkov, like Ulas, is merely spouting party propaganda, or if his former KGB experience has taught him to be wary of granting Russia’s intelligence agency too much power.

One thing that reports about the new law have in common — whether they emanate from inside or outside of Russia — is that they presume that communism in the former Soviet state is dead, while expressing concern that giving increased power to the FSB will mean a step backward in the march to freedom. For example, according to various press accounts the new law is "a step toward a police state," "a left-over order from the Soviet Union," etc.

What most commentators on this development fail to mention, however, is that communism never really died in Russia, it just assumed a more benign form in order to facilitate more favorable relations with the West. Where Stalin may have kept Russians on a three-foot chain, and Gorbachev lengthened the chain to 10 feet, Putin may have played out so much slack that Russians forgot the chain was there at all. The latest bill extending more power to the FSB is not the beginning of the Russian government placing new shackles on the Russian people, but merely a slight tightening of the slack on chains that have remained in place (however loosely) since the demise of the Soviet Union.

Since the official collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the key centers of power — political, economic, military, intelligence — in Russia and the other "former" Soviet states have remained in the hands of lifelong communists. President Dmitry Medvedev’s mentor, Vladimir Putin, joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union while he was a law student at Lenningrad State University. He joined the KGB while young and served the Soviet spy agency until 1991. In 1998, President Boris Yeltsin appointed Putin head of the FSB. In 1999, Yeltsin appointed Putin acting Prime Minister of the Government of the Russian Federation. Putin was elected President in 2000 and was reelected in 2004. Unable to serve for a third term, Putin was replaced by his hand-picked successor, Medvedev, who subsequently appointed Putin prime minister of Russia.

It is with some amusement, therefore, that we read complaints that the new restrictions are “a step toward a police state” from a spokesman from the Communist Party, the party that ruled the Soviet police state for 70 years. And while a former employee of the KGB (Gudkov) is certainly capable of recognizing "a left-over order from the Soviet Union," considering Vladimir Putin’s former career with the KGB, one is tempted to ask: “So what else is new?”

There is also an important lesson for Americans in what has just happened in Russia. The rationale for this latest curtailment of rights in Russia is the March 29 Metro bombings by Chechen separatists. The similarity of this thinking to our own government’s violations of protections found in the Bill of Rights is chilling. (Consider the National Security Agency’s warrantless surveillance as part of the war on terror.)

Fortunately for us, we have a Constitution and at least a few judges left willing to enforce it. In August 2006, U.S. District Judge Anna Diggs Taylor of Detroit ruled that warrantless wiretapping (war on terror or not) is unconstitutional.

"There are no hereditary kings in America and no powers not created by the Constitution,” noted Judge Taylor in her ruling.

The benefit of a system of government where rights are presumed to be inalienable and God-given, in contrast to the Russian system, where what the government grants the government can take away, is immediately apparent.

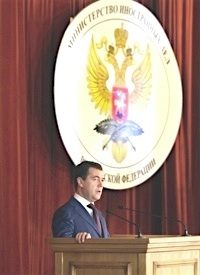

Photo: President Dmitry Medvedev speaks in the Russian Foreign Ministry headquarters in Moscow, July 12, 2010, during his meeting with Russia’s ambassadors: AP Images