Like many of America’s and the world’s tragedies, the chain of events that led to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki goes back to the great wielder of the big stick, the President who seldom walked softly, the much revered and overrated Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was fond of Japan and, as we all know, the old Rough Rider midwifed the treaty that ended the Russo-Japanese war, for which achievement he won the award that comes eventually to all great warriors, the Nobel Peace Prize.

Not content with governing a nation that spans an entire continent, with an ocean on each side, nor willing to settle for the rarely and feebly disputed rule of half the planet, Roosevelt envisioned what columnist William Norman Grigg has described as a "Monroe Doctrine for Asia," with Japan as the Eastern America. Japan could keep Russia in check, help open China to Washington’s corporate clients, and would not compete with the United States for control of the Philippines. It would be free to take dominion over Korea and Manchuria. With Japan as America’s junior partner, the United States would have plenty of room to expand and flex its muscles as a Pacific power, indeed the pre-eminent Pacific power. As is so often the case, the triumph of power politics was hailed with hosannas from the pulpit, as Manifest Destiny was portrayed as an extension of the Kingdom of Heaven.

"The victory of the Japanese is a distinct triumph for Christianity," said the Reverend Robert MacArthur of New York’s Calvary Baptist Church according to Grigg. "The new civilization of Japan is largely the result of Christian teaching. A very great proportion of Japan’s leading men today, especially those who fight her battles on land and sea, with such skill and valor, profess the Christian faith." To confirm the timeless observation that men tend to venerate and even worship their own self-image, Roosevelt conferred on the Japanese the title "honorary Aryans."

With the gift of hindsight, we know what TR’s foresight could not envision, that the Japanese would be allied with those not very honorary Aryans in Germany when Roosevelt’s cousin Franklin would be in the White House, and the Japanese would repay the United States with tons of steel dropped on the Naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Thus, would America be plunged into a two-ocean war with Germany and Japan that would leave her the undisputed mistress of land, sea, and air in the postwar world. Teddy Roosevelt and today’s "national greatness" conservatives and War of the Month Club Republicans would no doubt agree it was worth the expenditure in lives, limbs, blood, and tears to see America emerge as the world’s reigning superpower.

It would not be the sole superpower, however, as the Soviet Union, its population heavily reduced by the destruction of war, would nonetheless be the master of Eastern Europe and, with its partner in Peking, a force in Asia as well. World War II had barely ended when World War III loomed as a distinct possibility. The United Nations was hailed as "the last best hope" for peace in the world.

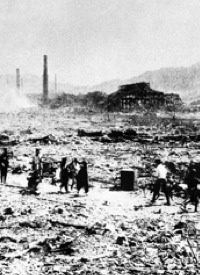

The horrors of World War II were most monstrously demonstrated in the Pacific, where the fierce, savage fighting between two of the world’s great civilizations, carried out on islands inhabited largely by primitives, left the primitives terrified of what civilization had wrought. And nowhere did the horrors grow more gruesome than in the two cities where the atomic bomb was dropped, on Hiroshima on August 6 and on Nagasaki, 65 years ago today, August 9, 1945.

Ironically, President Harry S Truman, so often celebrated for his plain-spoken candor, told the world that the atom bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima, "a military base," to avoid, so far as possible, the making of civilian casualties. Though there were some military facilities in Hiroshima, as well as some industrial sites, there could be no mistaking the fact that the world’s first atomic bomb had been unleashed on the civilian population of a city of some 300,000 men, women, and children of all ages, with death and destruction on a scale never before seen or imagined as the result of a single bomb. It violated all the known rules of civilized warfare, but to Truman and the "hawks" of World War II, it was not enough. Three days later, and one day after the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan, the United States dropped a second atomic bomb, this one on the port city of Nagasaki. Within days Japan surrendered, and the war was finally over.

Japan was defeated and her surrender inevitable before the first bomb. Russia’s entry into the war further sealed her doom. The biggest obstacle to surrender was the Allied demand that it be "unconditional." To the Japanese that meant the dethronement and possibly the execution of their Emperor, whom they regarded as a deity. Thus they were determined to fight to the bitter end. Only when the Emperor intervened and agreed to the surrender could the nation follow suit.

The destructive power of the A-bomb also sealed the fate of nations aligned under the new United Nations. Only under the aegis of an international peacekeeping agency, it was argued, could mankind escape an otherwise inevitable holocaust. The blasts also, by shortening the war, limited the advance of the Soviets into the Far East, though the Red Army captured enough of Manchuria to create a base for Mao’s army of insurgents and "liberated" enough of Korea from Japanese rule to create a puppet regime in North Korea and set the stage for the Korean War.

As for the Christian influence in Japan, it took a severe beating under Allied bombing. The bomb that landed in Nagasaki hit Saint Mary’s Cathedral, the largest Christian Church in the Far East. Many other Christian churches and schools in Japan were, of course, obliterated, not only by the two atomic bombs but by the fire bombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities that went on in the late stages of World War II.

The Nuremberg trials did not put Harry Truman or any of the victorious American, English, or Soviet statesmen and warriors in the dock, for to the victors went the spoils of World War II, and the victors wrote most of the official histories. But the bomb dropped on Hiroshima and the redundant bombing of Nagasaki three days later bear tragic witness to the likelihood that America, that "shining city on a hill" and its rulers may one day have to answer for the waste of lives, liberty, and property in a court much higher and more powerful than the one that tried Germans in Nuremberg.

Photo of Nagasaki after the bomb: AP Images