The United States invaded Afghanistan in October 2001. Six years later then-Senator Barack Obama, in a speech entitled “The War We Need to Win,” called Afghanistan “the right battlefield” in the Global War on Terror and pledged to “deploy at least two additional brigades to Afghanistan” if elected President. Since taking office he has made good on that promise, increasing troop levels by 17,000 in February 2009 and an additional 30,000 in December 2009.

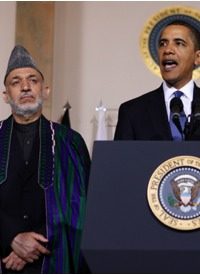

Now, after nearly nine years of war under both George W. Bush and Obama and two troop increases on his watch, Obama says the “war in Afghanistan will get worse before it gets better,” according to the Associated Press. Obama made remarks to that effect in a joint press conference with Afghan President Hamid Karzai at the White House on Wednesday.

If Obama’s comments sound familiar, it’s because those very words were uttered on October 1, 2008, by Gen. David McKiernan, then the top U.S. military commander in Afghanistan, as he pleaded for more troops and other aid. As the AP reported: “‘We’re in a very tough fight,’ McKiernan said. ‘The idea that it might get worse before it gets better is certainly a possibility.’” McKiernan got his troops, yet here we are, two years later, hearing the same line from Obama.

One might reasonably wonder if Obama has any real intention of beginning a withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan in July 2011, as he has stated. Even if he does begin withdrawing troops, to what extent does he plan to disentangle the United States from Afghanistan? He gave little indication that any significant disengagement would take place during his presidency, saying, “We are not suddenly as of July 2011 finished with Afghanistan. After July 2011 we are still going to have an interest in making sure that Afghanistan is secure, that economic development is taking place, that good government is being promoted.”

The President might want to try ensuring those things for Americans first. In just the past six months there have been two significant attempts at terrorist attacks in the United States — the “underwear bomber,” Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, and the Times Square bomber, Faisal Shahzad — neither of which was thwarted by federal law enforcement. The U.S. economy is barely limping along, with an official unemployment rate of nearly 10 percent (the actual rate is much higher). And no one who, for example, witnessed the arm-twisting, back-room deals, and secrecy surrounding the healthcare reform debate would describe what we have in Washington as “good government.”

Obama, like his predecessor, insists that “we are steadily making progress” in Afghanistan. U.S. officials have been making unannounced visits to both Iraq and Afghanistan for about as long as we’ve had troops there. One would think that after all the alleged progress we have made in both these countries it would be safe for them to make announced visits, but just this March President Obama sneaked into and out of Afghanistan, announcing his appearance only after the fact. With all this supposed progress, too, one might expect a more optimistic assessment than “the war will get worse before it gets better.”

The President took responsibility for civilian deaths in Afghanistan, claiming that “extraordinary measures” are being taken to avoid them. If this is true, then Obama deserves credit. However, given that his increased use of unmanned drones in Pakistan resulted in the deaths of perhaps 700 civilians in 2009 alone, his reassuring words must be taken with more than a few grains of salt.

Karzai, for his part, must realize that he needs Washington far more than Washington needs him. His authority has never extended much beyond the Kabul city limits, and his personal security detail has been supplied by Washington. For Washington he serves as a convenient figurehead to give the appearance of democracy — that “progress” we keep making — but, should he ever cross his benefactor on the Potomac, he could easily be replaced. Saddam Hussein, who was far more independent of Washington than Karzai, found himself transformed from a trusted U.S. ally to the “next Hitler” practically overnight when the mood in Washington shifted in 1990.

Karzai’s lack of acceptance among the general population is a major obstacle to Obama’s exit strategy, as the AP writes:

Obama’s Afghanistan exit strategy depends heavily on propping up a strong central government in Afghanistan. But U.S. military and civilian officials say that won’t be possible until the local population learns to trust the new authorities.

Only a quarter of the key regions in Afghanistan support or even sympathize with the government in Kabul, with large swaths of the country still hesitant to swing behind the U.S.-backed authority, according to a Pentagon assessment released last month.

Karzai’s dependence on Washington is also a significant obstacle to peace talks with the Taliban and other militants, according to the AP report:

Karzai appears to agree with outside analysts who say that senior Taliban, including some with blood on their hands, must be at the table for any serious negotiation to stick. The United States has ruled out discussions with anyone who has not renounced ties to al-Qaida, reflecting the sensitivity of cutting deals with people who were even indirectly responsible for the Sept. 11 attacks. The United States has not spelled out what middle ground it might approve however, and although Obama said the outreach effort must be managed by Afghans Karzai has said he needs U.S. backing before he makes a move.

Americans may see Karzai as an independent, democratically elected leader of Afghanistan, but Karzai clearly does not see himself the same way, and neither do most Afghans. Any exit strategy that depends on establishing Karzai’s government, or any other U.S.-backed central government, as a legitimate, accepted authority in Afghanistan is almost certain to fail.

The monthly cost of the Afghan war is now higher than that of the Iraq war, according to USA Today. At a time when the United States is also racking up record deficits — the April 2010 deficit was four times that of April 2009 — and making dangerous loan guarantees to failing European welfare states, it might seem prudent to begin seriously planning to withdraw from both Iraq and Afghanistan as soon as possible. Instead, Obama appears likely to delay withdrawal from Iraq and has signaled a long, open-ended commitment to Afghanistan, simultaneously laying out an exit strategy whose conditions will be next to impossible to meet.

Michael Tennant is a software developer and freelance writer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Photo of President Barack Obama and Hamid Karzai: AP Images