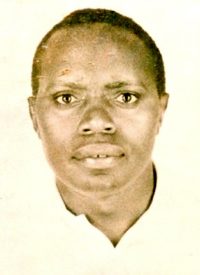

Following a decade-long trial, an international court sentenced Rwandan Maj. Gen. Augustin Bizimungu (left) to 30 years in prison for his alleged role in the 1994 genocide that left more than 500,000 ethnic Tutsis dead. Two other former military officers received 20-year sentences each.

According to the indictment, former army boss Bizimungu ordered his subordinates “to exterminate the small cockroaches” while supplying weapons and fuel for the genocidal campaign. He was also accused of preparing liquidation lists and allowing his troops to rape women and girls, along with an extraordinarily long list of other crimes.

Bizimungu pled not guilty to all the charges. But presiding international judge Asoka de Silva disagreed, saying the former general was responsible for the acts of his men. Said to be an “architect” and one of the masterminds behind the slaughter, Bizimungu could have been sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of genocide and “crimes against humanity.” But the tribunal decided on 30 years instead.

“It is a welcome decision,” said chief prosecutor Martin Ngoga after the ruling. “It is a big sentence, even if many people think he deserved the highest.” According to news reports, Bizimungu did not show any sign of emotion as the decision was handed down.

The ex-military leader, who assumed command of the Rwandan army shortly before the genocide began, managed to elude capture for almost a decade — even with a $5 million U.S. government bounty on his head. He was finally captured with rebels in Angola in 2002.

Two other senior military officers, Maj. Francois-Xavier Nzuwonemeye and Capt. Innocent Sagahutu, were also found guilty of crimes against humanity. They were charged with participating in the assassination of former Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana as well. Each of them was sentenced to 20 years.

Augustin Ndindiliyimana, the former leader of a paramilitary “police” squad that also participated in the genocide, was also found guilty. He was released, however, after having already served more than a decade in a Belgian prison. The tribunal ruled that he was not in full control of his men, and that he had shown signs of being opposed to the wanton mass murder.

More than half a million Tutsis were slaughtered during the 100-day-long genocide that rocked Rwanda in early-to-mid 1994. The brutality shocked the world. But the history leading up to the tragedy, of course, is long and complex.

Members of the minority Tutsi ethnic group had ruled the area for centuries before Europeans arrived. Even during the colonial period, the Tutsi monarchy was left in place. But after the colonizers left, civil war broke out between the majority ethnic group known as the Hutus and their former Tutsi rulers, with members of the Hutu majority eventually seizing power.

In 1994, the Hutu president’s plane was shot down close to the capital. Though later exposed as the probable work of Hutu extremists, the president’s assassination was immediately blamed on members of the Tutsi minority. So, with the leader’s death and after decades of intense rivalry, government-controlled media outlets and high-ranking officials — military and civilian — began carrying out a systematic attack against the Tutsi population.

Murder with machetes, widespread rape, burning of houses, and more became commonplace. Estimates of the death toll range from over 500,000 up to a million, with numerous anti-genocide Hutus also perishing in the conflict.

After months of the slaughter, armed Tutsi forces with the Rwandan Patriotic Front swept the country. Eventually they seized the capital, Kigali, and put an end to the genocide. The RPF, meanwhile, has also been accused of engaging in its own atrocities — especially in the Eastern Congo, where millions of civilians have perished in recent years, sometimes at the hands of United Nations-backed forces.

The United Nations, of course, had some “peacekeepers” in Rwanda before and during the genocide. Some eventually withdrew after 11 U.N. police were killed protecting the Prime Minister. But instead of preventing the slaughter, then-UN “peacekeeping” boss Kofi Annan ordered international forces to disarm civilians and collect non-government weapons — essentially leaving the victims of the eventual massacre totally defenseless in the face of military forces and government-backed militias.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), set up in neighboring Tanzania, was established by the United Nations Security Council in late 1994. It has held 50 trials and convicted almost 30 defendants, nearly all of them alleged to have been senior ringleaders in the genocide.

Among those convicted were several members of the press who were accused of inciting the madness. Many more cases are still winding through the tribunal.

While it is hard to dispute the notion that atrocities committed in Rwanda should be punished, there are more than a few critics of the international court currently purporting to deliver justice. Peter Erlinder, a professor at William Mitchell College of Law who has worked with the ICTR defense, claims the real criminals are currently in the Rwandan government. Others argue that reconciliation rather than vengeance is more urgently needed.

In the book Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide, author Linda Melvern exposes the complicity of some Western governments in the mass murder — conspirators who will likely never stand trial. The French, for example, allegedly trained the Rwandan forces who eventually perpetrated the slaughter. Then, under the guise of “international humanitarian intervention,” the government of France helped many of the key mass murderers escape justice.

Of course, there are also opponents of the whole principle behind “international courts” — tribunals that could theoretically put Americans on trial someday for loosely defined “international crimes,” all without respecting any of the rights enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Allowing U.N.-court precedents to continue being established, even in popular prosecutions, critics argue, could eventually lead to atrocities on a global scale under the banner of international justice.