Before the House votes on the resolution to condemn white supremacism and nationalism, its members might want to reconsider one of its clauses.

The target of the resolution is, of course, the reputed “white supremacism” of Iowa Representative Steve King, now the target of a Two Minutes Hate.

King uttered the unutterable — Western Civilization is a pretty good thing, he told the New York Times — and Official Washington got the vapors. “Western Civilization” really means “white supremacy,” and because King also used those radioactive words, all of us could be contaminated.

Fumigation is in order.

Problem is, the resolution that implicitly condemns King quotes a real white supremacist to make the point.

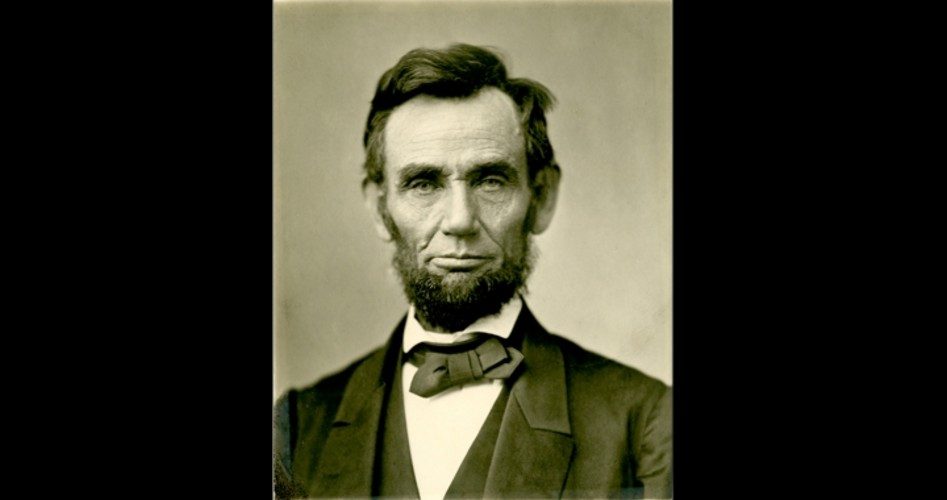

That would be Abraham Lincoln, who wanted to deport blacks after emancipation.

The Resolution

The anti-King HR 41 opens thusly: “Whereas, on January 10, 2019, Representative Steve King was quoted as asking, ‘White nationalist, white supremacist, Western civilization — how did that language become offensive?’’’

That quote came from the Times story about King, and despite his clear denunciation of the awful things he is said to have advocated, GOP leaders booted him off two committees and denounced him as a virtual air pollutant.

The resolution quotes Ronald Reagan and Martin Luther King, Jr., and implicitly connects Steve King to Dylan Roof, the nut who murdered nine blacks at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2017, and Robert Gregory Bowers, the nut who will stand trial for the murder of 11 people at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh.

As well, the many “whereases” include this one from Abe Lincoln:

Wise statesmen as they were, they knew the tendency of prosperity to breed tyrants, and so they established these great self-evident truths, that when in the distant future some man, some faction, some interest, should set up the doctrine that none but rich men, or none but white men, were entitled to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness, their posterity might look up again to the Declaration of Independence and take courage to renew the battle which their fathers began — so that truth, and justice, and mercy, and all the humane and Christian virtues might not be extinguished from the land; so that no man would hereafter dare to limit and circumscribe the great principles on which the temple of liberty was being built.

Lincoln uttered those fine words in Lewistown, Illinois, on August 17, 1858.

Apparently, authors of HR 41 didn’t bother to look up some of Honest Abe’s other sentiments.

Lincoln and White Supremacy

By today’s standards, Lincoln was the white supremacist, not King — the man denounced with Lincoln’s words.

Four days after he spoke the words in Lewiston that landed in HR 41, he offered these gems in Ottawa, Illinois, during his first debate with Stephen Douglas.

Anything that argues me into his idea of perfect social and political equality with the negro, is but a specious and fantastic arrangement of words, by which a man can prove a horse-chestnut to be a chestnut horse…. I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference.

The black man is “entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” Lincoln admitted, but “he is not my equal.”

At the fourth debate in Charleston, Illinois, a month later, Lincoln again argued for white superiority:

I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And in as much as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race. I say upon this occasion I do not perceive that because the white man is to have the superior position the negro should be denied everything. I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. My understanding is that I can just let her alone.

In Peoria, Illinois, in 1854, pondering what to do if the slaves were freed, Lincoln firmly stated that “we cannot … make them equals.”

Add to this another unpleasant truth. As the election of 1864 approached, the historical society that bears his name says, Lincoln “felt the need to tie emancipation with colonization to make emancipation more acceptable to conservatives. Colonization became a political tool in dealing with the issue of what to do with slaves freed during the Civil War.”

Lincoln actually did send 500 slaves to Haiti, which ended in the death of some, and on June 13, 1863, “signed an agreement with British Honduras to send free slaves to Belize. However the British pulled out of the agreement claiming neutrality in the Civil War.”

This, on the other hand, is what Representative King said after the left attacked: “We are all created in God’s image and that human life is sacred and all its forms.”