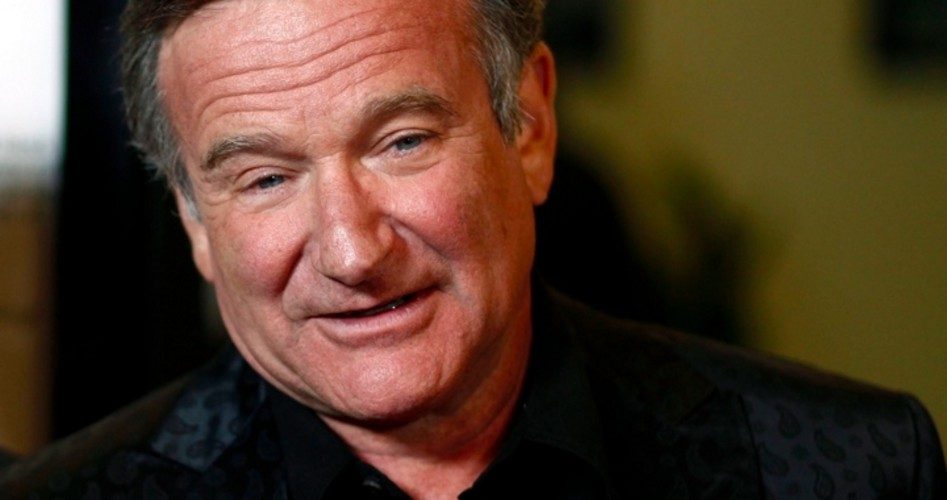

“There is a thin line that separates laughter and pain, comedy and tragedy, humor and hurt,” said columnist Erma Bombeck. On Monday, comedian and Golden Globe, Emmy, Grammy, and Oscar winner Robin Williams, finding himself lost on the wrong side of that line, hanged himself after a long bout with depression. It was an end that shocked and saddened many fans but that was also sadly stereotypical, giving weight to the claim that comedians ply their playful trade to cover up or deal with pain.

Whether this phenomenon is exaggerated or not, I knew an aspiring comedian who certainly fit that mold. He often was side-splittingly funny but never seemed happy; he could make you laugh but never laughed himself — I don’t remember a genuine smile ever crossing his face even once. And my erstwhile acquaintance and Williams have a lot of company. As Lenny Ann Low wrote in The Sydney Morning Herald:

There are many comedians who have been diagnosed with some form of mental illness: John Cleese, Paul Merton, Jim Carrey, Ruby Wax, Dave Chappelle, Robin Williams, Hugh Laurie, David Walliams and Bamford have all spoken publicly about dealing with depression.

British comedian Tony Hancock, lauded as the funniest comic actor of his time, was dogged by depression and alcoholism for much of his life. He killed himself while filming a television series in Australia in 1968.

… Two of Hollywood’s greatest comic performers, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, suffered from bouts of depression. Chaplin once said: ”To truly laugh, you must be able to take your pain and play with it.”

… Rhys Nicholson, a Sydney-based comedian who is outspoken about his depression and eating disorder, believes mental health issues are widespread in the comedy community.

Many other figures in the business concur. One of them is Jamie Masada, owner of famed L.A. comedy club The Laugh Factory. His establishment, writes Slates’ Peter McGraw and Joel Warner:

has an in-house therapy program. Two nights a week, comics meet with psychologists in a private office upstairs, discussing their problems while lying on a therapy couch formerly owned by Groucho Marx. “Eighty percent of comedians come from a place of tragedy,” explains … Masada. “They didn’t get enough love. They have to overcome their problems by making people laugh.”

And Williams certainly fit this mold. Bullied by peers, he suffered a loneliness as a child that “was not eased by his parents,” wrote Dominic Wills at Westlord.com. Wills elaborated:

[Williams’ father] Robert was away much of the time and, when he was home, Robin found him “frightening”. [His mother] Laurie worked, too, leaving Robin to be pretty much raised by the maid they employed. He later explained that, though he knew they loved him, they found it hard to communicate their affection. In fact, he says he began in comedy through his attempts to connect with his mother (“I’ll make Mommy laugh, and that will be OK”). Still, he was marked by the experience, being left with an acute fear of abandonment and a condition he describes as Love Me Syndrome.

Playing the clown also became a way to win the approval of those bullying peers, who made sport of the “short, shy, chubby and lonely” child, to use Williams’ description of his young self.

But while comedy can be used to win that audience adulation that never really satisfies the heart’s deepest yearnings, it can also be a good way to hide. And here I think not just of my old comedian acquaintance, but also a quick-with-a-quip Englishman I once knew who used humor as a defense mechanism. Any time a conversation threatened to penetrate his façade, jokes were deployed as a diversionary tactic. I don’t know if it was designed to keep others from knowing something he wanted hidden (likely) or to avoid possibly painful self-examination, or both, but his firewall of mirth was virtually impenetrable. Likewise, Jamie Masada said of Williams, “He was always in character. I knew him 35 years, and I never knew him.”

Science, too, tells us that comedians have much hidden. As Slate also wrote:

A recent article in the British Journal of Psychiatry detailed the results of 523 American, British, and Australian comedians’ self-assessment tests measuring psychotic personality traits. The researchers found that the comics did tend to score significantly higher for psychotic traits than the general population. (A control group of actors who took the test also scored higher than normal for psychotic traits but not as high as comedians.)

Yet so inextricably linked is comedians’ pain with their work, some say, that they couldn’t be successful without their pain. As Lenny Ann Low writes about comedienne Felicity Ward, “She says when she is filled with joy and her anxiety is calmed, her comedy skills and urges evaporate. ‘I went into a relationship last year and I was very happy,’ she says. ‘I thought, ‘It is very hard to write comedy when I’m really happy. I’ve got nothing to complain about’. Then, I had a three-month writing block.’” Next there’s comedian Rob Delaney, about whom Low writes:

[He] says he has swapped the drink and pills for writing and telling jokes.

Making people laugh, he writes, “makes me feel really, really f—ing good. I would even go so far as to say it gets me high.[”]

“And now I don’t drink or do drugs,” he told Slate magazine. “But when I get on stage, when I walk in front of an audience of hundreds or thousands, it really feels similar.”

This may sound like Captain Kirk in Star Trek V unforgettably saying that pain constitutes “the things we carry with us, the things that make us who we are. We lose them, we lose ourselves” before growling, “I don’t want my pain taken away. I need my pain!” But there may be a more intellectual explanation.

I had a great friend who for a time attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings (more as a diversion and to play sociologist as much as for any other reason). A brilliant man and true natural-born psychologist, he had a very astute observation about some of the attendees:

While they thought they were kicking addiction, they tended to just substitute one addiction for another.

In particular he cited a man who gave a testimonial saying (I’m paraphrasing), “Ever since I gave up booze, my libido has really spiked.” While some would say his sobriety was simply having positive health effects, my friend’s interpretation was that the man had actually transitioned from addiction to alcohol to addiction to sex.

This brings us to the very interesting book Positive Addiction, by late psychiatrist William S. Glasser. Glasser’s basic thesis is that negative addictions can be eliminated by supplanting them with “positive addictions,” such as exercise, art, music, and beneficial work, to cite just a few examples. And does it not smack of the very same thing when Rob Delaney says that performing on stage “really feels similar” to drinking or doing drugs?

But this raises a deeper question: What really is a positive addiction? While many in our libertine time would disagree, continually seeking cheap sexual thrills isn’t exactly positive. Some could even wonder if addiction to things such as exercise is truly positive. No, it won’t kill you most likely, but true health encompasses more than just the physical. And does placing something worldly at the center of your life, becoming obsessed with it, reflect balance and spiritual health?

As for performing, there’s no doubt Delaney is right: It can be addictive. The adulation, the applause, the roar of the crowd, the fame, and the acclaim. But what happens when the lights finally go out? Do you then become, to use Dick Morris’ characterization of Bill Clinton, like a solar panel, warm and electric when the sun is shining but cold and devoid of energy when your cloudy day comes? Note that it’s now being reported that Williams was depressed over his faltering career.

There’s also another factor. If Aristotle and other great thinkers were correct in citing virtue as a precondition for happiness, then entertainment is a breeding ground for depression. It is a corruptive atmosphere where vice is rampant and applauded; where sexual innuendo, profanity, and lewd and twisted humor are signs of “sophistication” and, all too often today, bring success. This miasmic culture is a major reason the annals of entertainment are replete with the names of performers of all stripes who, either through the slow suicide of drugs or alcohol or at the end of a rope, found untimely deaths at their own hand.

This is why some would say the only truly positive addiction is faith in God. And perhaps, just maybe, this missing factor among entertainers is what poisons the well — of the nation and of their own souls.

Photo of Robin Williams: AP Images