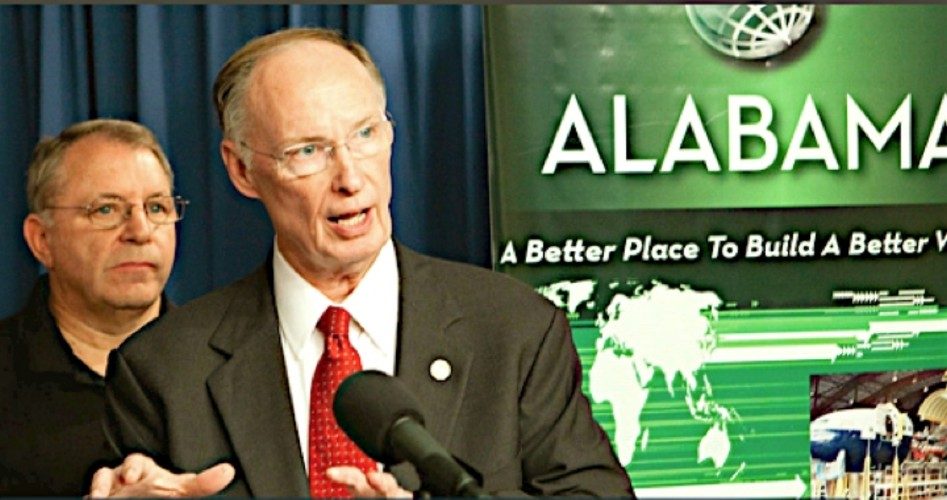

Two days into a special session of the Alabama state legislature called by Governor Robert Bentley (left), the governor failed to find a friendly lawmaker who would introduce his proposed amendments to the state’s immigration law.

The special session was called last week by Bentley in order to address issues related to redistricting, as well as the controversial immigration statute that has been the subject of lawsuits and fierce debate nationwide.

Bentley, a Republican, thought for a moment that his proposed slate of changes might stand a chance of coming before the state senate when it was attached to a bill offered by Republican Senator Scott Beason. Beason balked, however, and rather than allow Bentley’s bill to piggyback onto his own, he withdrew his measure altogether.

On Friday, the governor threw in the towel in his battle in the state House of Representatives, as well, ultimately signing H.B. 658 into law. That measure was itself an alteration to an earlier immigration bill that was intended to simplify the previous proposal.

Upon reading the writing on the wall, Bentley released a statement minimizing the personal effrontery of his legislative impotency.

“As we worked with legislators during the special session, it became clear that the Legislature did not have the appetite for addressing further revisions at this time,” Bentley said. “In an effort to remove the distraction of immigration from the other business of the special session, I decided to sign House Bill 658 and allow the progress made in the legislation to move forward. We can now also move forward on the other business of the special session.”

Resigned to defeat, Bentley bowed out gracefully.

“We needed to make [the immigration bill] better. And over the course of the legislative session, we did that,” Bentley said. “There is substantial progress in this bill. Burdens on legal residents and businesses are eased, and the goal remains the same — that if you live and work in Alabama, you must do so legally.”

There were many among those who had opposed the bill every step of the way that were disappointed in the governor’s surrender.

“The governor has been struggling to get votes for his amendments, but to give up after one day is dismal,” said Mary Bauer, a lawyer with the Southern Poverty Law Center, one of several organizations that have filed legal challenges to Alabama’s strict anti-illegal immigration law.

Not surprisingly, in a statement issued after the close of the legislative session, Bentley demonstrated that he did not share Bauer’s attitude about his accession:

Over the last several months, we worked closely with legislators to revise House Bill 56. The set of revisions that passed in the full House of Representatives and the Senate Judiciary Committee had my support. The bill that the full Senate ultimately passed was different and did not reflect all of the changes we had agreed upon. However, the bill did include most of the suggested revisions and represented substantial progress in simplifying the bill while keeping it strong.

That part of the law most troublesome to Bentley was the provision that requires the state’s public school districts to ascertain the immigration status of students. That provision remains tied up in federal court, pending the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of the Arizona immigration law, upon which the Alabama statute is based.

In one local newspaper, the governor was quoted as saying, “I still have concerns about the school provision in the original law,” Bentley said. “That provision is currently enjoined by a federal court, so it is not currently in effect, and we can re-address this issue if the need arises.”

The path to passage has been a long and winding one for the Alabama law. Earlier this year by a vote of 64-34 the Alabama House of Representatives passed alterations to H.B. 56, the state’s anti-illegal immigration bill. The result was H.B. 658, the current law.

The original version of the measure passed last year was described as “one of the toughest in the nation.” Unfortunately, it was just that harshness that forced the state legislature to make changes to the language so as to increase the state’s Attorney General’s ability to defend it in court against the various legal challenges that have been filed against it.

Changes made at that time to the law include carving out an exception allowing pastors to minister to congregants regardless of their immigration status, a clarification of law enforcement guidelines so as to prevent officers from inquiring into a person’s immigration status during routine roadblocks and traffic stops, and a removal of the requirement that proof of citizenship or legal residency be provided upon applying for utility services.

Supporters of the earlier iteration of the statute have by and large stood behind the changes, as they recognize the importance of passing a law that will withstand judicial scrutiny. Notwithstanding this realpolitik consideration, however, proponents remain adamant that their state repel any influx of illegal immigrants and that jobs offered by domestic businesses be kept available only to legal residents and citizens.

“We want to discourage illegal immigrants from coming to Alabama and prevent those that are here from putting down roots,” sponsor Rep. Micky Hammon (R-Decatur) said during debate.

Apart from the scrum among two branches of the state government, the federal bench will soon weigh in, as well.

In March a three-judge panel of the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta told representatives of Alabama and Georgia that they would await the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision in the Arizona immigration case before handing down a ruling of their own regarding the Alabama and Georgia statutes, both of which are in large part based on the Arizona measure.

The decision was a somewhat anticlimactic conclusion to this latest round of legal arguments over the constitutional situs of immigration authority.

Judges listened to about three hours of oral arguments from attorneys for the federal government and for the state governments of Alabama and Georgia. The former argued that the Constitution grants exclusive power to the federal government to set and administer laws for the control of immigration to the United States. For their part, state Attorneys General argued that the feds were derelict in their duty to thwart the unchecked influx of illegals into their respective state borders.

At one step in the process, Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange promoted the repeal of at least two of the law’s more controversial sections, both of which were not being enforced per an injunction handed down by the 11th Circuit Court. Specifically, the sections he suggested scrapping included one making it a crime for illegal aliens to be to be detained while not in possession of proper immigration documentation, and the aforementioned provision mandating that the state’s public schools maintain a registry of their students’ immigration status. Both provisions remain in the final version signed last week.

To its credit, Alabama consistently has defended its anti-illegal immigration law by pointing out that it contains provisions “safeguarding against unlawful discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin.” Such illustrations will likely be made in some future federal courtroom, as well.

The looming problem is that asking a federal court to restrain the powers of the federal government is like asking a drug addict to pass stricter drug laws.

In the end, Governor Bentley recognized the realpolitik atmosphere and signed the bill into law. Said the governor:

The bottom line is there are too many positive aspects of House Bill 658 for it to go unsigned. I don’t want to lose the progress we have made. This bill reduces burdens on legal residents as they conduct government transactions. The bill also reduces burdens on businesses while still holding them accountable to hire legal workers. These changes make this a stronger bill.