A new study reveals that between 480,000 and 507,000 people have been killed in the combat carried on by the United States in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan since September 11, 2001.

The Brown University report indicates that “this tally of the counts and estimates of direct deaths caused by war violence does not include the more than 500,000 deaths from the war in Syria, raging since 2011, which the US joined in August 2014.”

Lest anyone be underwhelmed by the death toll, the study’s authors report that their numbers “are an undercount.”

The study reveals:

Many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) attempt to track civilian, militant, and armed forces and police deaths in wars. Yet there is usually great uncertainty in any count of killing in war. While we often know how many US soldiers die, most other numbers are to a degree uncertain. Indeed, we may never know the total direct death toll in these wars. For example, tens of thousands of civilians may have died in retaking Mosul and other cities from ISIS but their bodies have likely not been recovered.

In addition, this tally does not include “indirect deaths.” Indirect harm occurs when wars’ destruction leads to long term, “indirect,” consequences for people’s health in war zones, for example because of loss of access to food, water, health facilities, electricity or other infrastructure.

Most direct war deaths of civilians in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and Syria have been caused by militants, but the US and its coalition partners have also killed civilians. Since the start of the post-9/11 wars, the Department of Defense has not been consistent in reporting on when and how civilians have been harmed in US operations. The US has attempted to avoid harming civilians in air strikes and other uses of force throughout these wars, to varying degrees of success, and has begun to understand civilian casualty prevention and mitigation as an essential part of US doctrine. In July 2016, the Presidential Executive Order on Measures to Address Civilian Casualties stated: “The protection of civilians is fundamentally consistent with the effective, efficient, and decisive use of force in pursuit of U.S. national interests. Minimizing civilian casualties can further mission objectives; help maintain the support of partner governments and vulnerable populations, especially in the conduct of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations; and enhance the legitimacy and sustainability of U.S. operations critical to our national security.”

It’s not as if the rotation of regimes has slowed the pace of the killing. The Brown University report found, for example, that “the number of civilians killed in Afghanistan in 2018 is on track to be one of the highest death tolls in the war.”

As reported by Jennifer Wilson and Micah Zenko, in Foreign Policy in August 2017, “Judging from Trump’s embrace of the use of air power — the signature tactic of U.S. military intervention — he is the most hawkish president in modern history. Under Trump, the United States has dropped about 20,650 bombs through July 31, or 80 percent the number dropped under Obama for the entirety of 2016.”

As I reported for The New American in March 2017:

Do the maudlin math: despite his promises to reduce American intervention in foreign affairs and despite his oath to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States,” under President Trump, these deadly drone strikes have increased 432 percent over the reprehensible pace set by his predecessor.

The purpose of this article, though, is not to prove that President Trump is as committed to carrying on the work of death undertaken by his predecessors. The purpose of this article is to familiarize readers with the fact that our Founding Fathers shared neither the boundless bellicosity nor the inhumane interventionism of our contemporary elected leaders.

What follows are statements by a few of the first rank of members of revered Founding Fathers.

First, we present the man described as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen,” President George Washington. This quote is from his famous Farewell Address, delivered in 1796:

As avenues to foreign influence in innumerable ways, such attachments are particularly alarming to the truly enlightened and independent patriot. How many opportunities do they afford to tamper with domestic factions, to practice the arts of seduction, to mislead public opinion, to influence or awe the public councils. Such an attachment of a small or weak towards a great and powerful nation dooms the former to be the satellite of the latter.

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow-citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government. But that jealousy to be useful must be impartial; else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defense against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots who may resist the intrigues of the favorite are liable to become suspected and odious, while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people, to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop. Europe has a set of primary interests which to us have none; or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns.

Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.

Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one people under an efficient government, the period is not far off when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel.

Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice?

It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world; so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it; for let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing engagements. I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy. I repeat it, therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But, in my opinion, it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Next, this quote taken from a Christmastime address to Congress given by President James Madison in 1816:

My country will exhibit … a Government which avoids intrusions on the internal repose of other nations, and repels them from its own; which does justice to all nations with a readiness equal to the firmness with which it requires justice from them; and which, whilst it refines its domestic code from every ingredient not congenial with the precepts of an enlightened age and the sentiments of a virtuous people, seeks by appeals to reason and by its liberal examples to infuse into the law which governs the civilized world a spirit which may diminish the frequency or circumscribe the calamities of war, and meliorate the social and beneficent relations of peace; a Government, in a word, whose conduct within and without may bespeak the most noble of all ambitions — that of promoting peace on earth and good will to man.

President Madison’s predecessor, Thomas Jefferson, promoted a similarly pacific policy in a letter written in 1817:

“Our wish for the good of the people of England, as well as for our own peace, should be that they may be able to form for themselves such a constitution & government as may permit them to enjoy the fruits of their own labors in peace, instead of squandering them in fomenting and paying the wars of the world.”

In a letter written in 1787, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and co-author of The Federalist, John Jay, warned of the waging of unjust war:

But the safety of the people of America against dangers from foreign force depends not only on their forbearing to give just causes for war to other nations, but also on their placing and continuing themselves in such a situation as not to invite hostility or insult; for it need not be observed, that there are pretended as well as just causes of war.

It is too true, however disgraceful it may be to human nature, that nations in general will make war whenever they have a prospect of getting anything by it; nay, that absolute monarchs will often make war when their nations are to get nothing by it, but for purposes and objects merely personal, such as a thirst for military glory, revenge for personal affronts, ambition, or private compacts to aggrandize or support their particular families or partisans.

Finally, in a speech delivered in 1821, President John Quincy Adams eloquently explains the rightful role America should play in promoting the freedom and peace of other nations:

Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will commend the general cause by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example. She well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force…. She might become the dictatress of the world. She would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.

May we remember the virtue of our Founders, may we remember the value they put on human life — all human life — may we heed their warnings against involving ourselves in foreign conflicts, and may we remember the necessity and moral certainty that God would absolve them of sin before they would act to take the life of another man.

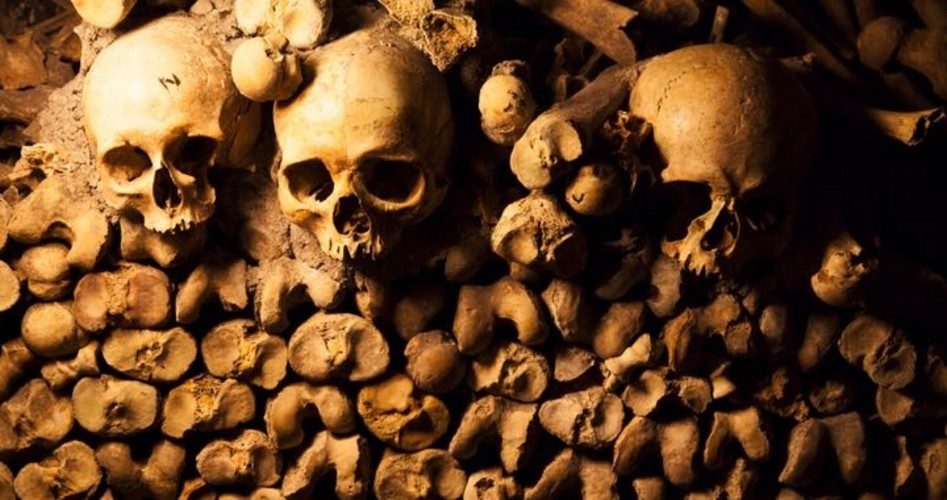

Photo: Clipart.com