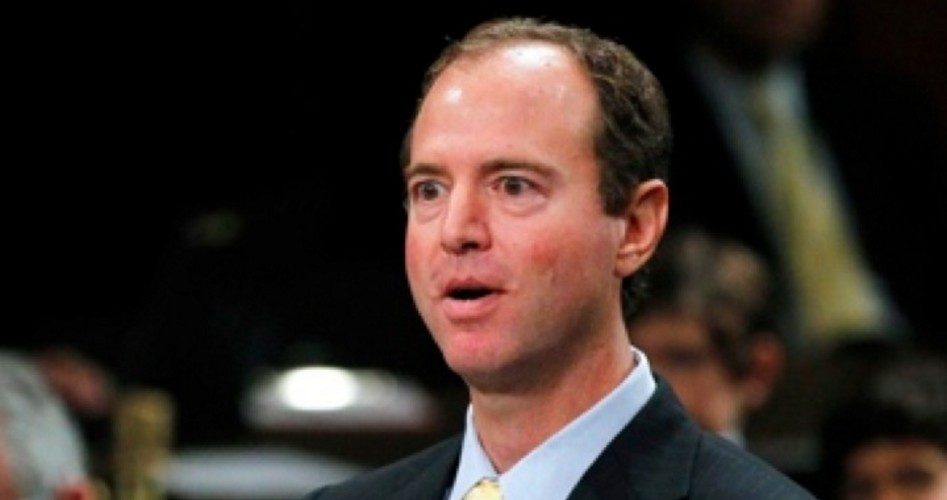

A California congressman is preparing legislation to repeal the post-9/11 legislation that two presidents have relied on as justification for waging war in several countries simultaneously against persons or organizations believed to be involved in terrorist attacks or the planning of them. Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.; pictured) told Spencer Ackerman of Wired that he plans to introduce a bill to “sunset” the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), passed by nearly unanimous votes in Congress on September 18, 2001, just one week after terrorists flew hijacked airplanes into the Twin Towers in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

“The current AUMF is outdated and straining at the edges to justify the use of force outside the war theater,” Schiff told Wired magazine, an online journal on trends in technology. The publication also reports extensively on politics, especially on issues affecting electronic privacy. Both the Bush and Obama administrations have relied on the Joint Resolution as authority for “everything from the warrantless electronic surveillance of American citizens to drone strikes against al-Qaida offshoots that did not exist on 9/11,” Wired noted.

The resolution has also been interpreted to authorize the targeted killing of alleged terrorists, including U.S. citizens in foreign lands abroad who are actively engaged plotting terrorist attacks on the United States. In his speech at the National Defense University May 23, Obama said that to capture such individuals and put them on trial is not always feasible. He described as necessary the September 2011 killing by drone strike of the American-born Muslim cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, whom he identified as the chief of external operations for al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Awlaki helped oversee a plot to bomb two U.S-bound cargo planes in 2010 and was behind a foiled attempt to detonate explosives aboard a plane when it was landing in Detroit on Christmas Day, 2009, Obama said.

“I would have detained and prosecuted Awlaki if we captured him before he carried out a plot, but we couldn’t,” he claimed. “And as president, I would have been derelict in my duty had I not authorized the strike that took him out.”

In the same speech, the president said he would work with Congress in exploring options for “increased oversight” of targeted killings and to “refine and ultimately repeal” the AUMF. “Our systematic effort to dismantle terrorist organizations must continue,” he said. “But this war, like all wars, must end. That’s what history advises. That’s what our democracy demands.”

Previous efforts to repeal the AUMF have gone nowhere. Rep. Barbara Lee, another California Democrat, cast the only vote in Congress against the resolution at the time of its passage and has tried several times to repeal it. After Republicans won a majority of the House seats in the 2010 elections, Buck McKeon (R-Calif.), incoming chairman the Armed Services Committee, said it was time to revise the authorization. Noting that it grants authority for using military force against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks, McKeon argued that the administration lacked legal authority to combat al-Qaeda affiliates that have sprung up since then in places such as Yemen and East Africa. But the Obama administration at that time showed no interest in revisiting the authorization. The resolution, as passed, is “sufficient to address the existing threats I’ve seen,” Jeh Johnson, then the senior lawyer for the Department of Defense, told the committee at a March 2011 hearing.

Schiff said the end of the U.S. combat mission in Afghanistan, scheduled for the end of next year, might be a good time to repeal the AUMF, but he admits to having “only a less clear idea of what should follow.” The Afghan war was initiated in October of 2011, as the beginning of the war on terror, since the Taliban regime in Afghanistan was believed to be harboring al-Qaeda units and training camps. In 2010, Leon Panetta, then director of the CIA, said there were no more than 50 to 100 al-Qaeda left in Afghanistan. But the war on terror has also included U.S. aerial attacks in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, and some members of Congress seem interested in expanding, rather than limiting, the president’s authority to wage war on other groups designated as terrorist organizations. An aide to the House Armed Services Committee said McKeon is not in tune with his California colleague on repeal.

“The chairman is far from convinced that’s the direction we need to go,” the spokesman told Wired. “We need to reaffirm our authority with respect to those [al-Qaeda-] affiliated groups.”

Obama said May 23 he will not sign any legislation expanding the AUMF mandate. But he also pledged that the United States will continue “a series of persistent, targeted efforts to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America” in places such as Yemen, Somalia, and Mali. The president quoted James Madison’s warning that “No nation could preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare.” But when Assistant Secretary of Defense Michael Sheehanasked was asked at a recent Senate hearing how much longer the war on terror is likely to last, he replied: “At least 10 to 20 years.”

Given the 12 years since it started, that would add up to “at least” 22 to 32 years of continual warfare. There is no time limit in the Authorization for Use of Military Force, but nearly a quarter to a third of a century in a military campaign without a declaration of war by Congress might be stretching the constitutional authority of the commander-in-chief a bit. Even some of the Senate’s leading hawks in the war on terror have voiced concerns over the breadth, if not the duration, of the war-making authority administration officials claim the president has under the AUMF. John McCain (R-Ariz.) said at a recent Senate Armed Services Committee hearing that the authority “has grown way out of proportion and is no longer applicable to the conditions that prevailed, that motivated the United States Congress to pass the resolution in the authorization for the use of military force that we did in 2001.”

“For you to come here and say we don’t need to change it or revise or update it, I think is, well, disturbing,” he told the four senior military officials testifying before the committee. “I don’t blame you because basically you’ve got carte blanche as to what you are doing around the world.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) asked if the AUMF gives the president the authority to put “boots on the ground” in Yemen or the Congo.

“Yes, as long as the purpose was targeting a group associated with al Qaeda that intended to harm the United States or its coalition partners,” responded Robert Taylor, acting general counsel for the Department of Defense.

“This is the most astounding and disturbing hearing that I’ve been to since I’ve been here,” said freshman Sen. Angus King (I-Maine). “You guys have essentially rewritten the Constitution today.”

“The testimony I hear today suggests the administration believes that they would have the authority to go into Syria,” said Tim Kaine ( D-Va.), referring to the civil war between rebel forces and Syrian president Bashar Hafez al Assad. “But I don’t want us to walk out of the room leaving an impression that members of Congress also share the understanding that that would be acceptable.”

But would Congress assert its constitutional authority to prevent the president from taking the nation into another undeclared war? On that point the nation’s lawmakers appear to have, in Rep. Schiff’s words, “only a less clear idea.”

Photo of Rep. Adam Schiff: AP Images