While the flags of the United States, Germany, and the European Union fluttered in the warm breeze behind them, the trio of leaders gazed at the assembled press corps. At 1:18 p.m., President Bush addressed the gathering.

“Thank you all, please be seated,” President Bush began. “Welcome to the Rose Garden. I want to welcome Angela Merkel and Jos Barroso here. Thank you all for your friendship, thank you for what has been a serious set of discussions,” the president said in his characteristic drawl.

Without further preface, he then described the outcome of recent U.S.-EU negotiations.

“I told the chancellor and the president that the EU-U.S. relations are very important to our country,” the president continued, “that not only is it important for us to strategize how to promote prosperity and peace, but it’s important for us to achieve concrete results. And we have done so. I thank the chancellor and Jos very much for the trans-Atlantic economic integration plan that the three of us signed today. It is a statement of the importance of trade. It is a commitment to eliminating barriers to trade. It is a recognition that the closer that the United States and the EU become, the better off our people become. So this is a substantial agreement and I appreciate it.”

With that, the president announced a wide-ranging agreement that committed the United States of America to a path that would see the nation shed its long-cherished independence in favor of integration with the European Union. As described by the White House itself, the U.S.-EU summit:

• “Adopted a framework on transatlantic economic integration which lays a long-term foundation for building a stronger and more integrated transatlantic economy, in particular by fostering cooperation to reduce regulatory burdens and accelerating work on key ‘lighthouse projects’ in the areas of intellectual property rights, secure trade, investment, financial markets, and innovation.”

• “Adopted a declaration on political and security issues,” including the seemingly mutually exclusive goals of combatting terrorism and working “towards visa-free travel for all EU and U.S. citizens by creating conditions by which the Visa Waiver Program may be expanded.”

• “Adopted a joint statement on energy security and climate change” that commits the United States to working collectively with the EU to ensure “secure, affordable, and clean supplies of energy and tackling climate change.”

What seems like a revolutionary step toward transatlantic merger was little remarked in the press. The entire event seems to have occurred in a vacuum. There was little or no coverage of possible discussion of transatlantic integration in the years before the summit and, over the past year, there has likewise been little or no coverage of subsequent developments. It seems almost as if the agreement hammered out between the White House and the European Union was a freak occurrence, a political accident of nature. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth.

In fact, quietly and behind the scenes, a very active if unofficial and non-governmental effort has been underway to grease the skids for transatlantic merger. The effort has been led by a little-known non-governmental organization (NGO) that has been working to advance plans to merge the United States with Europe. Few have heard of the work of this group, the Transatlantic Policy Network (TPN), because it has never been covered by the mainstream media. That is a particularly interesting fact, given that TPN’s supporters and collaborators include many powerful and well-known corporations, think tanks, and legislators on both sides of the Atlantic. That they are cooperating in an effort to merge the United States and the EU would seem to be at least marginally newsworthy.

Even though the mainstream media can’t be bothered to report on it, the American people might be interested to learn that TPN’s plans are not just talk. Working carefully, if quietly, since the early 1990s, the organization has moved quickly to gain the agreement of leaders on both sides of the ocean that further integration is necessary and desirable. Now, transatlantic integration is much closer to reality than anyone would suspect.

Merger Ahead

In February 2007, ahead of the U.S.-EU Summit, TPN published its white paper entitled Completing the Transatlantic Market. In that paper, the organization summarized its goals. The executive summary states:

It is time for a complementary, top down approach to transatlantic cooperation through a joint commitment by the European Union and the United States to a roadmap for achieving a Transatlantic Market by 2015 and creation of an overarching framework for dialogue and action to achieve that goal.

The emphasis placed on “top down” is not insignificant. As typically used by NGOs, that terminology usually implies that executive-level leaders will impose their desires on the citizens of a nation, not the other way around as envisioned, for instance, by America’s Founders.

That aside, is the plan as described by the TPN white paper, really anything to worry about? After all, isn’t a common “Transatlantic Market” just a matter of economics and trade policy that will have little or no effect on the sovereignty and independence of nations?

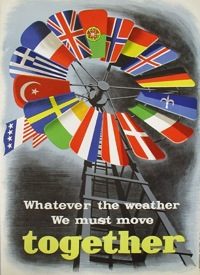

The experience of Europe over the last 60 years demonstrates that the creation of a common market is only a first step toward more thorough integration. The European Union itself started life as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), an intergovernmental organization formed in the aftermath of World War II ostensibly to give a boost to the coal and steel industries in European nations ravaged by war.

But the ECSC was only meant to be a first step to further economic and (eventually) political integration. In 1957, it was superseded by the European Economic Community (EEC) that was created by the Treaty of Rome. The EEC, which was also known as the Common Market, became the European Community, the immediate predecessor of today’s European Union.

The progression from common market to political union as it occurred in Europe should not be mistaken for a singular and unusual event. It is, in fact, the process through which other international political mergers are expected to occur. The process was explained by University of Nevada professor of economics Glen Atkinson. In a paper published in the Social Science Journal entitled “Regional Integration in the Emerging Global Economy,” Professor Atkinson explained:

The lowest level of integration is a free trade area that involves only the removal of tariffs and quotas among the parties. If a common external tariff is added, then a customs union has been created. The next level, or a common market, requires free movement of people and capital as well as goods and services. It is this stage where institutional development becomes critical. The stage of economic union requires a high degree of coordination or even unification of policies. This sets the foundation for political union.

If TPN succeeds in catalyzing the existence of a transatlantic common market by 2015 as planned, that will be only one short step removed from actual political integration.

Integration Milestones

On its website, TPN proudly lists some of its “achievements” in building the framework for a common market. “In a short space of time,” the organization says, it has “built a credible ‘network of networks’ linking the political, business and academic communities. It confirmed its value to members by helping to shape key developments in the EU-US partnership during the 1990s.”

According to the organization, some of its achievements include:

• Creating the “New Transatlantic Agenda” in December 1995, described by TPN as “a blueprint for joint action by the US and the European Union across all of the most important political, economic, security and social aspects of their relationship.”

• Launching the “Transatlantic Business Dialogue” also in 1995, “with a specific objective to remove the trade and investment obstacles to the creation of a real transatlantic marketplace.”

• Creating the “Transatlantic Economic Partnership (TEP)” at the London EU-U.S. Summit in May 1998. According to the organization, “TEP identified a series of elements for an initiative to intensify and extend multilateral and bilateral cooperation and common actions in the field of trade and investment, including formal trade negotiations and trust enhancing measures.”

These efforts have garnered significant transoceanic support, both from political and business leaders. In 2004 and again in 2005, the EU parliament passed resolutions “in which the concept of completing the transatlantic market by 2015 is supported.” TPN notes with apparent satisfaction that the U.S. Congress has done likewise and points out that the “House of Representatives has also passed a resolution endorsing the concept of a ‘Transatlantic Partnership Agreement’ between the EU and the US.”

For those keeping track of congressional malfeasance, this legislation, House Resolution 390, was introduced in the House by Nebraska Republican Doug Bereuter on October 2, 2003. It passed the House little more than a month later on November 5. The resolution found that the “United States and the European community are aware of their shared responsibility, not only to further transatlantic security, but to address other common interests such as environmental protection, poverty reduction, combating international crime and promoting human rights, and to work together to meet those transnational challenges which affect the well-being of all.”

Moreover, it found that because of the “threats posed by global terrorism, terrorist states, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and the nexus of the three, the partnership should be expanded progressively from a transatlantic community of values to an effective transatlantic community of action by developing a collaborative strategy and action plan for dealing with those challenges of mutual interest and concern.” (Emphasis added.)

Support Network

The passage of the Bereuter resolution in the House in 2003 strongly indicates that the TPN plan has the widespread support of influential members of Congress. It is not necessary to look far to find just how many influential legislators have backed the transatlantic integration plan.

One such backer was the late Republican Congressman Henry Hyde of Illinois, the powerful and influential former chairman of both the House Judiciary and International Relations Committees.

In its “Partnership Report” of June 2004, TPN notes that Hyde spoke in favor of creating an EU-U.S. common market during a speech in Rome on June 29, 2003. According to the TPN report, Hyde “stressed the need for a ‘Transatlantic Economic Framework with the free movement of goods, services and investments.” That, as economist Glen Atkinson pointed out, is the very definition of a common market.

But Hyde wasn’t finished. He returned to this in a speech given in Chicago in September of 2003. In that speech, TPN points out, Hyde argued that America’s “economic relationship with Europe receives too little attention” and that the United States should be looking more closely at “the benefits to be obtained from closer cooperation across the Atlantic.” Accordingly, TPN notes, “Hyde called for the establishment of ‘a true Atlantic Marketplace’ and urged the EU and the US to ‘convene a high-level meeting of our respective regulatory policy-makers and regulatory bodies to try to establish common objectives in regulation and devise a process of formulating complementary regulations.’ ”

To put this in proper perspective, it should be noted that harmonization of law and regulation is a necessary prerequisite that must be accomplished before any economic or political integration of nations can occur. Finally, in 2004, Hyde, along with Congresswoman Jo Ann Davis (R-Va.) and Minister of the European Parliament (MEP) Jim Nicholson, who was serving as Chairman of the European Parliamentary Delegation to the United States, signed a joint statement “calling for a barrier-free transatlantic market by 2015,” thereby officially endorsing the plan preferred by TPN.

There are many other important legislators on both sides of the Atlantic who continue to back the integration plan, and some of them actually serve as leaders within TPN itself. The most prominent of these is Republican Senator Robert Bennett of Utah. Bennett is chairman of the TPN Management Committee, one of the top leadership positions at TPN, according to the organization’s website. The honorary U.S. president of TPN is Robert S. Strauss, a key Carter administration official and former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. Joining Strauss and Bennett in TPN leadership positions are:

• Former Congressman Jim Kolbe (R-Ariz.) — now senior transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the U.S., another group promoting U.S.-EU integration;

• Democratic Congressman Ron Kind of Wisconsin, who has been an active supporter in Congress of regional free trade agreements;

• Former Congressman Mike Oxley (R-Ohio), infamous coauthor of the notorious Sarbanes-Oxley Act that, as described by Congressman Ron Paul, unconstitutionally gave “the federal government authority to regulate the accounting standards of private corporations” in the wake of the Enron and other financial scandals of the early part of the decade.

In addition to these U.S. legislators serving in leadership positions with TPN, there are many others who are members of TPN’s “U.S. Congressional Group.” These include six senators — the aforementioned Senator Bennett of Utah, Thad Cochran (R-Miss.), Chuck Hagel (R-Neb.), Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.), Pat Roberts (R-Kan.), Gordon Smith (R-Ore.) — and 49 representatives. Some of the noteworthy members of the latter cohort include former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee F. James Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.), recently deceased Chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee Tom Lantos (D-Calif.), Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee John Dingell (D-Mich.), and current House Minority Leader John Boehner (R-Ohio). It seems that selling out U.S. sovereignty is a very popular and bipartisan pastime.

The Usual Suspects

Among businesses and think tanks one finds the usual crowd of internationalists heading up the lists of those supporting the TPN program of transatlantic integration. European and American business members include such influential companies as Boeing, BASF, Microsoft, Coca Cola, General Electric, IBM, Time Warner, Walt Disney, Wal-Mart, Xerox, Merck, Nestle, UPS, and a host of others. The inclusion of media titans Time Warner (owner of CNN), General Electric (NBC), and Disney (ABC News) perhaps explains in part the media blackout on the coverage of TPN’s activities.

Among think tanks, the TPN membership list is a who’s who of internationalism-promoting groups. Included on the list is the granddaddy of them all, the Council on Foreign Relations. Joining the CFR is the Atlantic Council of the United States, which seeks a “healthy transatlantic relationship” as “an essential prerequisite for a stronger international system.” Other organizations serving as TPN members include:

• The Brookings Institution

• The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

• The Chamber of Commerce of the United States

• The German Marshall Fund of the U.S.

• The Centre for European Policy Studies

• The European Roundtable of Industrialists

• Institut Francais des Relations Internationales

All of these and several other groups have lent their support to the TPN goal of creating a Transatlantic Market by 2015. As umbrella organization TPN points out, this market is to be created by executive decree from the top down, and that is exactly what has been happening. Meanwhile, the citizens who are being herded into this arrangement have no say in the matter. In fact, they are being kept in the dark.