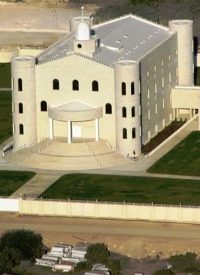

In a surprise attack coordinated by the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) on April 3-4, the Rangers and sheriffs removed an initial group of the 468 children at the Yearning for Zion Ranch (YFZ) in Eldorado, Texas. The raid was initiated with a court order — not a warrant — authorizing them only to have “investigatory access” to a particular teenage mother and her child, neither of whom actually existed. Soon thereafter, the rest of the 468 children were removed, with over a thousand government agents participating in the raids at a cost of nearly $2.3 million according to the Associated Press. The basis for taking these children was a false report to a child-abuse hotline that a teen girl was being forced into an underage marriage at the YFZ Ranch, owing to beliefs of their Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS) religion.

This article does not attempt to analyze the FLDS religious belief system, nor does it endorse or disapprove of it. The issue of taking children from any family — regardless of its ideology — must be governed by law and due process, not hysteria over religious or political beliefs fanned by a statist press corps.

It will be useful to chronicle the actions of the Texas child protection agency in the FLDS case — based on my review of the actual court documents, case plan, affidavits of the social workers, warrants, and detailed written accounts of the two-day hearing in court — with a critical eye to see how these same tactics are used in individual actions against innocent families nationwide. Thus, families can be prepared to defend themselves against false allegations of abuse, and not become victims like the children of the FLDS group.

State Child Protection, Wholesale Version

The Texas DFPS first got involved with the families at the Yearning for Zion Ranch when a woman from Colorado phoned a report to the Texas child-abuse hotline on March 29. This woman, Rozita Swinton, age 33, falsely identified herself as a 16-year-old named “Sarah,” from the YFZ Ranch, and stated that she had an eight-month-old child, and was pregnant again by her 50-year-old husband. This Colorado call originated from a person known to be a serial false reporter with a criminal record for making false reports. However, the agency used it to seize on the opportunity that they apparently had been waiting for — a plausible excuse to raid this ranch.

This fraud points to the widespread potential for manipulation in the child-abuse-hotline reporting system. Any disgruntled neighbor, angry ex-spouse or boyfriend, roommate, or enemy can make an anonymous false report and be believed. A mere allegation from such a person will prompt the agency to literally knock down the door to get into a home to check on the children. If and when the agency figures out it has been played for a chump and has improperly brought down the entire weight of the law on an innocent family, a great deal of harm has already been done, as is the case with the children at the YFZ Ranch.

Once the DFPS agency had the false report from “Sarah,” it enlisted legions of law-enforcement personnel and carried out the April 3 military-style raid of the YFZ Ranch starting at 9:00 p.m., without a warrant or a court order. Published photographs show that the Texas Rangers and sheriffs used armored personnel carriers, snipers, and riot gear to force their entry. Once in, agents of the DFPS carried out interviews of parents and children throughout the night and into the next day, and the agents took trucks-full of documents.

The agency readily determined that there was no “Sarah” at the ranch, and no “husband” abusing her. In fact, court records indicate that the agency found no credible evidence of any abuse whatsoever in any home at the YFZ Ranch. However, as the night-time raid stretched into the following day, officials proceeded to remove all 468 children at the ranch from their homes, most under the age of five, starting at 3:00 a.m. Texas law allows removal of a child only if “there is an immediate danger to the physical health or safety of the child,” or if it is clear that “the child has been the victim of sexual abuse.” (Tex. Fam. Code, Sect. 262.104(a))

One can imagine the terror that these babies and toddlers felt being ripped from their mothers in the middle of the night by armed strangers. The abducted children were then farmed out to various foster homes around the state, separated from parents and split off from their siblings. This allowed the state to begin accessing large federal reimbursements for foster care, and to unleash an army of social workers, therapists, and state lawyers.

Next, the state put on a show trial on April 17 and 18, to officially verify that the children needed to be rescued from their parents. This hearing was conducted in the District Court for Schleicher County in San Angelo, Texas, presided over by Judge Barbara Walther. Press accounts described the trial with headlines like, “Chaos Rules at Sect Trial,” as could be expected at a proceeding involving 468 children, their parents, and their lawyers. To make matters worse, prior to the trial, the judge had issued a separate order confiscating all the cellphones belonging to both the children and their parents, so that they could not even talk to their lawyers or to each other.

The gist of the state’s complaint was that female children at the ranch were being groomed for marriage to older men at too young an age and that male children were being encouraged to be sexual predators. The agency asserted that 31 children, aged 14 to 17, were pregnant or had borne children by adults. However, the agency now admits that over half of those 31 persons are actually adults, including one who is 27 years old. At the time of the hearing, the agency could not identify a single child married below the legal age, including the nonexistent “Sarah.” (Texas law allows marriage at age 16, or younger with court approval.) Nor was there testimony that any person was physically abused at the ranch.

The DFPS argued, as a reason to take the children, that “there is a mindset that even the young girls report that they will marry at whatever age, and that it’s the highest blessing they can have to have children.” Thus, in the agency’s view, inculcating respect for motherhood is “abuse.”

A review of the trial transcript shows that the judge made no pretense of providing due process, or of trying to decide the cases on an individual basis. Key evidence included a recommendation from a psychiatrist that the children not be returned to their homes, a psychiatrist who admitted that he got most of his information from the media and had never spoken to the leaders of the community. Several DFPS supervisors also testified, repeating the party line about abuse, although they could not cite any instance of it. The state also failed to provide evidence, as required by both federal and state law, that it had made reasonable efforts to keep the children with their parents prior to removing them.

After the two-day preliminary trial, and without hearing any evidence of abuse and neglect, the judge ruled that the DFPS would keep custody of all the children.

After the agency secured possession of the children, they then imposed a case service plan on each parent, which was put together by “culturally sensitive” experts. The plan, which pre-supposes abuse, sets forth tasks that the parents must do, such as taking parenting classes and undergoing psychological evaluations. In reality, these plans contain boilerplate provisions that are primarily designed to provide information to the agency to use at the final trial against the parents — a tactic I’ve seen repeatedly in my legal representation of families torn apart by the so-called child-protection services.

A cover letter of the “plan” contained the following statement: “CPS’s [Child Protective Service’s] investigation of the Yearning for Zion Ranch found evidence under Texas law of sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. Because of what CPS found, CPS removed your child from the ranch. After a hearing, the judge agreed with CPS’s belief that your child was not safe from abuse. The judge gave CPS temporary custody of you [sic] child.”

Happy Ending Elusive

A crack in the foundation of the case came after several of the FLDS parents petitioned the Texas Appeals Court, which quickly overturned the district-court custody order, and threatened to act if the court “failed to comply.” The May 22, 2008, opinion was unflinching in its condemnation of the agency’s actions. The court found that there was no evidence that male children or pre-pubescent females were in any danger of abuse. There was no evidence as to whether the small number of pregnant teens — five in all — were married or were victims of abuse. The court stated bluntly that “there was no evidence of any physical abuse or harm to any other child.”

The appeals court also noted that DFPS had not “made reasonable efforts to eliminate or prevent the removal of any … children.” The district court had made a perfunctory certification that such reasonable efforts were made, but that was exposed as a false finding by the appeals court.

The appeals-court ruling was a huge public embarrassment for the agency and a repudiation of the DFPS position. The agency was certainly not going to allow the largest child-protection case in United States history to be thwarted without a fight, so it immediately appealed to the Supreme Court of Texas. In a brief five-page opinion, the highest court affirmed that the appeals court was correct when it overturned the district-court order, for the same reasons, i.e., that there was no evidence of abuse. The opinion stated tersely, “On the record before us, the removal of the children was not warranted.”

Despite these state high-court rulings, the agency and the district court are placing numerous restrictions and qualifications on the children’s return. The district court is keeping the case open and demanding that parents cede much of their family liberty and privacy as a price for getting their children back.

DFPS has prepared a draft court order for Judge Walther’s signature that requires that parents let DFPS agents enter their homes at any time to inspect them, and allows the DFPS to order psychological testing for the children and parents, as well as to obtain medical exams of the children at any time and place. The agency wants no family member to travel more than 60 miles from home and desires photo identification of all parents and children. The form parents must sign before release of their children chillingly states: “By my signature … I accepted physical possession of the above-referenced child for the Department of Family and Protective Services.” This is a raw power grab, and it is unclear whether or how the higher court might react to this apparent contempt of its order.

But That’s the Way We Always Do It

The tactics perpetrated on the YFZ families are the same ones that CPS uses in almost every child-protection removal case nationwide: insufficient investigation, a superficial initial hearing, a boilerplate case plan whose real purpose is to provide evidence to the agency, splitting children in foster care and moving them far from family, a low standard of proof for abuse, and failure to use reasonable efforts to avoid removal from the home, among others.

What turned this situation around was the extensive publicity that exposed the normally hidden agency wrongdoing. These revelations forced the higher court to reverse the rulings of the agency and of the lower court, which was acting as a puppet of the agency. If each of these 468 cases had been adjudicated individually, hidden from public scrutiny in secret courtrooms as the law provides, the agency might have won most of them, despite having no evidence.

As of this writing, the YFZ families have won an important round in their fight, by getting the Texas Supreme Court to order the return of their children. As of Monday, June 2, the judge had signed a temporary order allowing return of the children to their families, with the many restrictions outlined above.

This temporary order will be in place only until a full trial of the matter, or until the agency comes up with more reasons to take the children away again. It is uncertain what the ultimate outcome of this case will be. The matter could end in a trial, the outcome of which could be anything from full vindication of the parents and dismissal of the case, to a permanent removal and adoption of all the children. Or the Texas DFPS could ultimately decide that it acted without a basis, and ask the court to dismiss the case. Nothing is predictable in child-protection cases, but it should be. The reluctance of District Court Judge Walther to follow the law and provide due process for the affected families compounds the problem.

It is easy to get caught up in the media hype regarding the alleged practices of this religious sect, and thus consider the removal of their children necessary or justified. However, our Constitution guarantees freedom of religion and the right to direct the upbringing of one’s children without government interference, in absence of criminal action. All parents are entitled to due process prior to having their children taken, and this was not provided by either the agency or the court. If the state can take children without due process from this religious group, then it can take them from anyone whose religious or personal beliefs are disfavored by the state.

This episode should be a warning to all families that an arbitrary attack by the state against a family can happen to any of us and that a court will likely not protect the family from overreaching state social workers or false reports of child abuse.

Gregory A. Hession practices constitutional and family law in Springfield, Massachusetts.